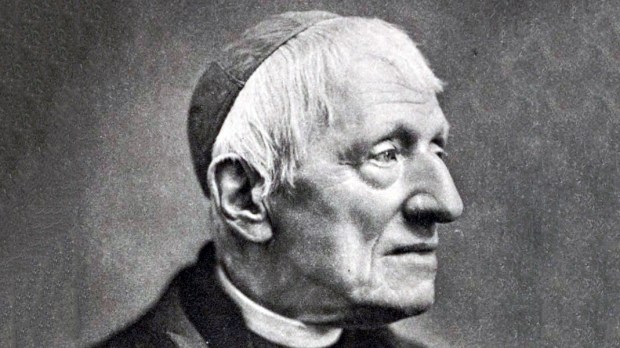

In October 2019, the great 19th-century Anglican convert Blessed John Henry Newman will at last be raised to the altars. The event will hold special significance for the Personal Ordinariates, jurisdictions whose mission it is to rebirth the Anglican Christian patrimony within the Catholic Church.

Nearly a decade after Pope Benedict XVI released Anglicanorum coetibus and created these entities, the canonization should bring a renewed focus on how this witness can be carried forward.

Flourishing and moving forward

These first years have seen flourishing work and prayer. Not only former Anglicans, but Catholics from many different backgrounds participate in Ordinariate parishes. Their fruits even include a budding renewal of theGilbertine monastic tradition. Founded in 1131 and once popular in England and Wales, this monastic order was suppressed under King Henry VIII. A small community has existed in Calgary, Alberta, since 2017.

Yet there is much more to do. Like all Catholics, Ordinariate communities are called to witness to the world around them. In an 1873 sermon, Newman could stillstate that, “Christianity has never yet had experience of a world simply irreligious.” Nearly a century and a half later, these parishes exist in a society and culture where the sacred has largely ceased to exist. The work of the Ordinariates takes place as communities scattered across lands of apostasy.

Exemplars can be found among the Ordinariate’s own spiritual ancestors. A similar ethos existed among the Anglo-Catholic slum parishes of the 19th century, linked to the Oxford movement that Newman himself spearheaded. Economic destitution had created a religious vacuum in the life of many working-class families. Anglo-Catholic clergy and laypeople undertook missions into such communities, typified in parishes like central London’s St. Alban the Martyr. There, curate Alexander Mackonochie held daily services, ran schools and soup kitchens, arranged workingmen’s clubs, and even heard confessions—a practice scandalous to less Catholic-minded Anglicans.

But while the movement preached the gospel through liturgical beauty and Christian life, it could not arrest broader social currents. Many Anglo-Catholics ultimately walked the road to full Catholic unity; the society around them abandoned even what it had until then retained.

Throughout the long 20th century, the Church pursued a renewed witness. In 2015, Pope Francis contributed to this teaching via the encyclical Laudato si’. Its central perception is that modern life has reshaped human nature according to a mechanistic and technocratic mode of being.The Holy Father hoped for communities to overcome this paradigm:

An authentic humanity, calling for a new synthesis, seems to dwell in the midst of our technological culture, almost unnoticed, like a mist seeping gently beneath a closed door. Will the promise last, in spite of everything, with all that is authentic rising up in stubborn resistance?

In the Ordinariate’s mission to be a sign of contradiction, the slum parishes are merely one example. Another is the witness of the Recusant martyrs: St. Edmund Campion, St. Robert Southwell, St. Anne Line, and many others. Undergoing extreme repression, they found themselves on the periphery of not only their local communities, but also that of the broader Catholic world. Priests and laymen alike forsook safety on the continent and embraced martyrdom—and thus the Catholic faith survived. In doing so, they echoed the very first missionaries to the British Isles. Like the Recusant martyrs, the Ordinariates owe their patrimony to witnesses like St. Augustine of Canterbury, St. Columba, St. Patrick, and others who gave witness and shed blood on these far-flung islands.

A different periphery

To fulfill its mission, the Ordinariates will need to journey out toward a different kind of periphery. In a culture that has left utter spiritual destitution in its wake, many are seeking those very treasures offered by their sacred patrimony. Perhaps one of the greatest examples is the Anglican Divine Office. This historic tradition, with its highest expression in choral Evensong, declares that the beauty of the liturgy rightly fills daily life.

This historic tradition, with its highest expression in choral Evensong, declares that the beauty of the liturgy rightly fills daily life.

Nevertheless, this earthly work in no way precludes the ultimate apocalypse in which the Church participates. The English theologian Fr. Aidan Nichols, O.P., whose works are popular among Ordinariate members, emphasizes the point in his book Christendom Awake:

At the moment God’s Kingdom, present sacramentally in the Church, in her preaching, in the holy signs of her worship, and in her saints, is hidden “kenotically” … in the ambiguities of time. But then the veil will be rent, and the hitherto invisible presence become plain. We already share in the transfigured cosmos whose nucleus is Christ’s risen and ascended body and are activated by its energies. But then we shall see the glorified Savior as the Lamb of the new temple …

The beauty of Christian life is precisely the beauty of this transfiguration. In a world reduced to the peripheries of spiritual life, the tradition of the channel-crossing missionaries, the Recusants, the slum parishes, and of the soon-to-be St. John Henry Newman is needed more than ever.