From the immigrant waves of Irish, Poles, and Italians, to the later influx of Latin Americans, New York City has long been a vibrant Catholic stronghold. Such history makes it seem especially strange that there was a time when just being a Catholic priest in NYC was a criminal offense legally punishable by death.

This remarkable law, which has long since been abolished, was enforced only one time. And it was enforced on John Ury, a graduate of Britain’s Cambridge University who was working in NYC as a Latin instructor.

Ury had lived in the city for only a short time, and some of his neighbors began to suspect that he was, in reality, a Catholic priest. The fact that he specialized in teaching Latin likely added to this suspicion, as the ancient Roman language was heavily linked to the Catholic Church.

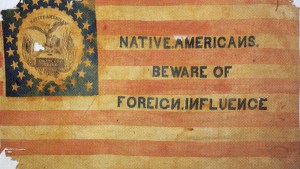

He had entered a climate of intolerance and paranoia. As Britain had been involved in a succession of wars with Spain, there were concerns that the Catholic nation would use fellow Catholics to infiltrate British colonies and attempt to create unrest.

Read more:

Catholic Emancipation in Britain opened up a second spring for the faith, 190 years ago

There were also concerns that the city’s increasing slave population – which had reached about one-third of the overall population of 12,000 – created a serious risk for rebellion.

Following a series of suspicious fires during March and April 1741, the tension was palpable. When there surfaced a purported grand conspiracy involving black slaves and poor whites seeking to overtake the city, “Father Ury” was pegged as a ringleader.

Ury was not actually a Roman Catholic, but instead a non-juror of the Church of England. The “non-juror” designation refers to Anglican clergy who refused to profess an oath of allegiance to the British Crown.

The trial of John Ury commenced on July 29, 1741. Mary Burton, a 16-year-old indentured servant, was the prosecution’s lead witness. She testified that Ury was baptizing black slaves at a local tavern and then encouraging them to commit arson and murder – sins which he, as a Catholic priest, had the power to forgive.

Read more:

Who were the “Know-nothings”? What was “Know-Nothingism”?

Burton, whose court statements were at times inconsistent and who also reportedly received payment for her testimony, related that there had been a plan to set fire to a Protestant church on the most recent Christmas Day. She added that Ury suggested to postpone the arson to a warmer day so “that the roof might be dry” and more conducive to the flames.

According to the prosecution, Ury’s destructive ambitions were due to his being employed “by other popish priests and emissaries.” Another reason was “his zeal for that murderous religion: for the popish religion is such, that they hold it not only lawful but meritorious to kill and destroy all that differ in opinion from them, if it may serve the interest of their detestable religion.”

The prosecution then launched into an attack on the “absurdities” of transubstantiation, the Catholic doctrine that the substance of the bread presented for the Eucharist changes into the Body of Christ. Somehow the court deemed all this as relevant to the case.

As no lawyer was willing to assist him, Ury had to defend himself. He provided witnesses who testified that he was indeed a Latin teacher. He also endeavored to show that he was no “papist” but, rather, an Anglican. However, no one was listening. He was found guilty on July 29, the same day the trial began; the 12-person jury took all of 15 minutes to deliberate.

In the court’s view, there were two reasons for executing Ury: The first reason was for him being “an Ecclesiastical person, made by authority pretended from the See of Rome and coming into and abiding in the Province of New York.” The other reason was for his role among the “Conspirators in the Negro Plot to burn the city of New York.”

While in jail awaiting execution, Ury wrote a speech that addressed his impending fate. “I am now going to suffer a death attended with ignominy and pain; but it is the cup that my heavenly father has put into my hand, and I drink it with pleasure.” He went to the gallows on August 29.

Ury was by no means the only one who received severe punishment for the alleged conspiracy. In fact, 18 black residents of NYC were hanged, while 14 others were burned at the stake, and an additional 71 were banished to faraway lands. Several other white persons, including the owner of a tavern where the purported conspiracy began, also went to the gallows.

With all the accused troublemakers either hanged, burned, or exiled, the city held a day of celebration on September 24.

The demise of the non-Catholic Ury serves as a vivid example of just how intense anti-Catholic hostility was in that era. Over the years, many martyrs have entered a volatile situation ready and willing to die for their religion. Ury does not belong to this category: He was forced into dying for a faith that wasn’t even his.

Far from being an agent of violent rebellion, chances are that the only thing Ury was plotting was how to deliver his next Latin lesson. His “martyrdom” may not have been the most glorious, but it certainly was strange.

Read more:

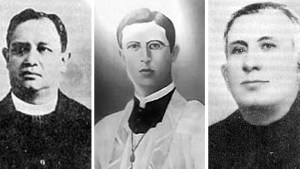

Meet 3 heroic priests who died in Mexico’s Cristero War