Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The veneration of relics is one of those Catholic traditions that appears to many non-Catholics as superstitious, and to many non-Christians as just downright weird. Why, when you could pray directly to God, would you ask a saint to pray for you? And why on earth would you go so far as to kiss a little golden holder with a piece of that saint’s clothing—or even of his or her body?

Mythical or macabre though it may seem, this ancient practice stretches back to the earliest days of the Church, when Christians would preserve and honor the bodies of martyrs in places like the catacombs. It’s also arguably rooted in deeply human instincts. After all, don’t we often ask our loved ones to pray for us, visit their graves when they’re gone, and keep common artifacts from their lives as if they were priceless riches?

Treasures of the Church, a Catholic ministry run by Fr. Carlos Martins of the Companions of the Cross, aims to “give people an experience of the living God” by means of such veneration. The ministry travels throughout the world, by invitation, to offer veneration of 150 genuine relics in the Church’s possession.

My wife encouraged us to attend one such event recently on Long Island, and I went without much research or forethought about what it was. It turned out to be a truly extraordinary experience—in fact, one of the greatest privileges in my life as a Catholic.

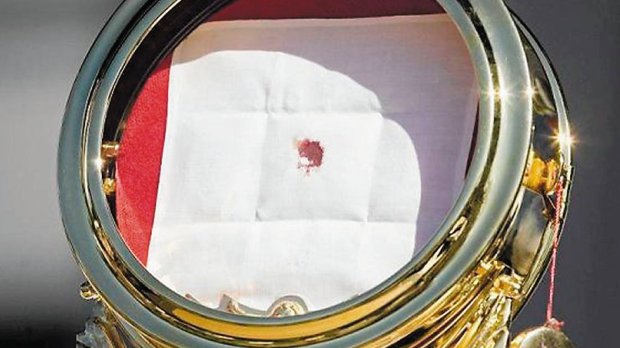

After a brief talk from Fr. Martins—one offering not just scriptural and historical perspectives, but also an evangelical clarion call to return to the sacraments—the crowd filtered across the street into a large hall, where columns of tables draped in blue cloth were dappled with small reliquaries and text descriptions.

As we moved through the room, I was increasingly astounded by the names I was seeing. Even from a secular perspective, this was a hugely impressive historical exhibition: from towering figures of Church history like St. Peter, St. John, St. Paul, St. Benedict, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas Aquinas, right up to more contemporary figures like St. Maria Goretti, St. John Paul II, St. Maximilian Kolbe, St. Edith Stein, St. Teresa of Calcutta, and Bl. Solanus Casey—just to name a few. There they all were, all made present in some mysterious way, for the attendees to freely hold, kiss, or pray with. If all of that weren’t impressive enough, at the front of the room were tables draped in gold cloth—the only tables, we were instructed beforehand, we couldn’t pick anything up from—adorned with relics from the Holy Family’s life, including the cloak of St. Joseph, the veil of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the true cross of Jesus.

This hall filled with the Catholic faithful bustled with excitement and devotion. At times that energy titled toward the wonderfully weird (“Has anyone seen St. John the Baptist?” one woman hollered—where else would you ever hear a question like that?). But for the most part, the mood was deeply thoughtful and prayerful. Many people were holdingrosaries or photos of loved ones—older parents, younger children—that were lovingly touched against the relics. Who knows what journeys of suffering, heartache, and longing, what aching petitions went into these moments?

In the 3rd century, the Emperor Valerian was persecuting the Christians and demanded that the pope’s protégé, Lawrence, turn over all the riches of the Church in three days. Brandon Vogt explains what happened next:

Lawrence worked swiftly. He sold the Church’s vessels and gave the money to widows and the sick. He distributed all the Church’s property to the poor. On the third day, the Emperor summoned Lawrence to his palace and asked for the treasure. With great aplomb, Lawrence entered the palace, stopped, and then gestured back to the door where, streaming in behind him, poured crowds of poor, crippled, blind, and suffering people. “These are the true treasures of the Church,” he boldly proclaimed.

As impressive as the relics were, it was a privilege to watch these “true treasures” of the Church—her suffering people—venerate them so lovingly.

Many of the visitors probably traveled far and wide for the experience of seeing and touching these reliquaries. But later, as I reflected on the event, I was struck by something. As Catholics, we believe that during any given Mass in any local Catholic Church, we can see and touch the real presence of Jesus Christ—body, blood, soul, and divinity—in the “reliquary” of the appearances of bread and wine. And not only that: we can, if properly disposed, actually eat his body and blood, welcoming him under the “roof” of our lives—our hungry bodies, minds, and souls—in the most direct and powerful way imaginable. “Christ is eaten,” Sacrosanctum Concilium says, “the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.” Has the sheer regularity of the Mass, and perhaps a good deal of poor faith formation, dulled our minds to how mind-blowing and life-giving an encounter this is? If a Treasures of the Church exposition could generate that much awe, how much more so should the Eucharist?

I would highly encourage any Catholic to see whether there is a Treasures of the Church exposition in your area—and if not, to look into inviting them. But if it doesn’t work out, remember the great treasures of the Church just around the corner.