Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

It wasn’t the Bible. Nor was it Thomas a Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ, which is an all-time best-seller after the Bible.

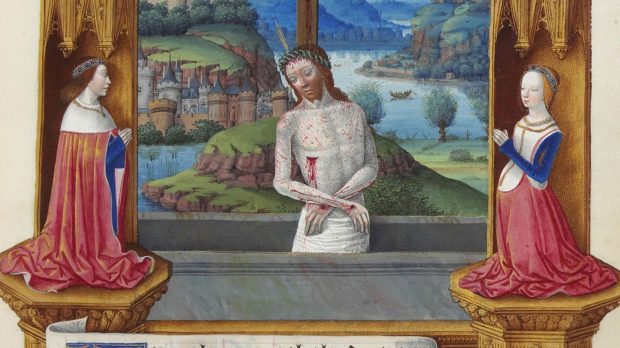

But, during the Middle Ages, the best-seller title goes to the Book of Hours, a devotional text with richly ornate and detailed illustrations that were commissioned by the nobility and other wealthy families for their own private use. According to the Met, more Books of Hours were produced than another kind of book in the Middle Ages.

The Book of Hours first started appearing in the 13th century and focused on devotions and prayers to Mary and Jesus organized according to the canonical hours of monastic prayer. For example, Matins (sunrise) was dedicated to the Annunciation, the Nativity was at Prime (6 a.m.), and the Annunciation to the Shepherds was at Terce (9 a.m.). The Hours of the Cross likewise follows Jesus at key moments of His Passion.

The devotion was modeled after the Divine Office, which was recited in monasteries at specific hours of the day. There were eight sets of prayers in the Book of Hours, meant to be said over a 24-hour span of time.

Some books also had other elements, such as a set of gospel lessons, the psalms, and prayers to saints known as Suffrages, according to the Met. Calendars reminded patrons of important feasts and saints’ days.

The Book of Hours remained popular up to 1700.

One of the most famous examples is the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry), which dates back to the 14th and 15th centuries in France, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. It is now held at the Musée Condé in Chantilly. The book includes images of the duke’s residence and also features calendars painted by the Limbourg brothers.

The Metropolitan Museum has three copies of the Book of Hours at the Cloisters: the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, and a diminutive manuscript by Simon Bening. Each is a “masterpiece,” showcasing the work of some of the most important artists of the time, according to the Met.

The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux was made for a fourteenth-century queen of France, and diminutive size, gossamer-thin parchment, and delicate painting by Jean Pucelle all contribute to its exquisite femininity. It includes a Life of Saint Louis, the king of France who was great-grandfather of Jeanne d’Evreux (54.1.2, fols. 154v–155r). Each of the Hours of the Virgin is introduced not only with the traditional scenes from Jesus’ infancy, but also a dramatic scene from the final days of his life, known as the Passion, on the facing page (54.1.2, fols. 82v–83r). All are rendered in grisaille, black and white drawings with lightly tinted backgrounds and other areas.

Other notable Book of Hours include the Book of Hours of Charles of Angoulême and the Livres d’Heures de Rohan in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.