Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Click on that icon on the top left of your document, and voilà. You just got yourself some nice text printed, in a blitz. But is it a thing of beauty?

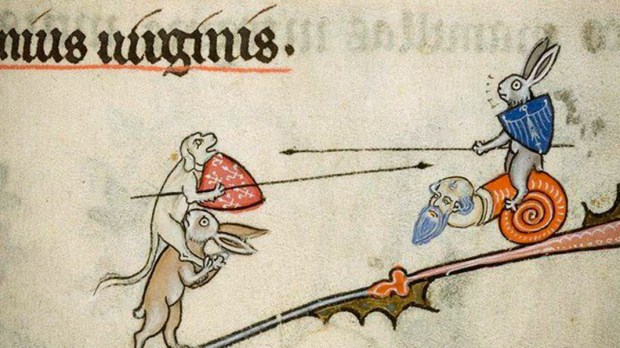

It might be hard to imagine for some, but for many centuries reproducing any given text was far from being an easy, quick thing. In the days of yore, way before the era of desktop inkjet printers, patient, laborious, attentive monks would engage in the painstaking work of creating a manuscript from scratch, moved by religious zeal and devotion as well as a profound understanding of beauty and truth and the need to preserve them in a volume able to endure the passing of time. In fact, the word “manuscript” derives from the Latin for “written” (scriptus) “by hand” (manus): it was all handmade, patiently, sometimes taking years.

In more than a sense, these craftsmen knew the preservation of wisdom, knowledge, and faith depended on them doing their job properly – something the ease with which we download and print PDFs nowadays probably makes it difficult to comprehend for us, used as we are to mass production and best-sellers.

The kind of specialized craftsmanship these medieval copyists and artisans had to put into the making of every manuscript can be properly appreciated in a series of seven videos the British Library has released. In them, the professional calligrapher and illuminator Patricia Lovett reproduces the many different processes and techniques these monastic craftsmen had to use when designing an illuminated manuscript page, from making a quill pen and ink to the line marking of a medieval book.

We probably don’t need to go through such painstaking processes to get our work done nowadays, but we can certainly learn a lot about attentiveness to detail, focus, work ethics, and caring for the most minute things (all these being most important tools for our spiritual and moral lives) from these monastic craftsmen.