Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

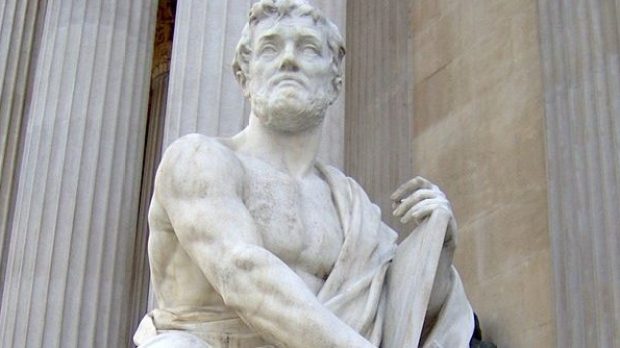

Tacitus is known for his chronicles of the Roman Empire, but he was also a high official in Rome’s imperial administration. Among the many stepping stones he had in his career, there is one that, in light of Christian history, suggests why he might have included a certain Jesus of Nazareth in his famous history, the Annals.

In A.D. 88, at the age of 22, Tacitus “became a praetor and a member of the priestly college that kept the Sibylline Books of prophecy and supervised foreign-cult practice,” the Encyclopaedia Britannica tells us.

Might it be that without his religious duties in the Roman Empire, Tacitus might have ignored the troublesome prophet in Palestine? He even wrote about Jesus’ crucifixion and Pontius Pilate’s role in his death.

Then again, there were Christians living in Rome, and a historian like Tacitus, born 25 years after the crucifixion, would have wondered who these people were and why they believed the way they did.

Tacitus refers to the Christians of Rome in the context of the great Roman fire of A.D. 64. He says that to dispel rumors that Nero was to blame for the fire, he:

… fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind.

He then describes the torture of Christians:

Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.

The 2018 film Paul, Apostle of Christ makes use of this detail. As St. Luke, portrayed by Jim Caviezel, furtively makes his way through the streets of Rome in order to visit the Christian community there, we catch a glimpse of a man tied to the side of a building, about to be set on fire in order to illumine the darkened streets.

Scholars have debated the authenticity of the Christian references in Tacitus. But Lawrence Mykytiuk, associate professor of library science and the history librarian at Purdue University, wrote in the Biblical Archaeology Review that Tacitus was “among Rome’s best historians—arguably the best of all—at the top of his game as a historian and never given to careless writing.”

“Earlier in his career, when Tacitus was Proconsul of Asia, he likely supervised trials, questioned people accused of being Christians and judged and punished those whom he found guilty, as his friend Pliny the Younger had done when he too was a provincial governor,” Mykytiuk wrote. “Thus Tacitus stood a very good chance of becoming aware of information that he characteristically would have wanted to verify before accepting it as true.”