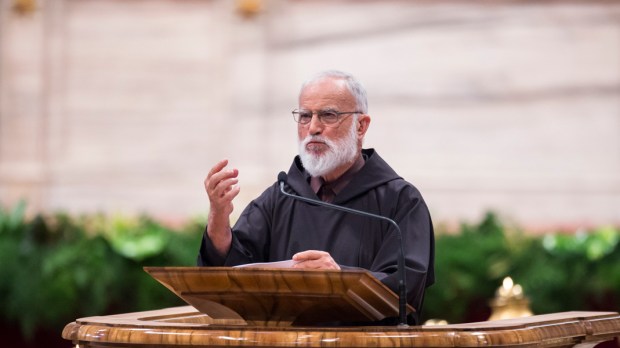

Here is the third Lent sermon of 2019 from Capuchin Father Raniero Cantalamessa, preacher of the pontifical household.

~

Idolatry: the antithesis of the living God

Every morning, when we wake up we have a particular experience that we almost never notice. During the night, the things that exist around us are the way we left them the night before: the bed, the window, the room. Perhaps the sun is already shining outside, but we do not see it because our eyes are closed and the curtains are drawn. Only when we awake do things begin or revert to existing for me because I become aware of them, I recognize them. Prior to that, it was as though these things did not exist.

The same thing is true with God. He is always there: “In him we live and move and have our being,” says Paul to the Athenians (Acts 17:28). But generally this occurs like our sleep, without our being aware of it. There is also an awakening of the spirit, a sudden burst of consciousness. This is why Scripture exhorts us so often to wake from our sleep: “Sleeper, awake! / Rise from the dead, /and Christ will shine on you” (Eph 5:14); “It is now the moment for you to wake from sleep” (Rom 13:11).

Idolatry, Ancient and New

The God of the Bible is defined as “living” to distinguish him from idols that are dead things. This is the struggle that appears in all the books of the Old and New Testaments. We only have to open a random page from the prophets and the psalms to find the signs of this epic battle in defense of the one and only God of Israel. Idolatry is the exact antithesis of the living God. One psalm says of idols,

Their idols are silver and gold, the work of human hands. They have mouths, but do not speak eyes, but do not see. They have ears, but do not hear; noses, but do not smell. They have hands, but do not feel; feet, but do not walk; they make no sound in their throats. (Ps 115:4-7)

In contrast to idols, the living God appears as a God who “does what he pleases,” who speaks, who sees, who hears, a God “who breathes!” The breath of God has a name in Scripture, the Ruah Yahweh, the Spirit of God.

The struggle against idolatry did not conclude, unfortunately, with the end of historical paganism; it is always on-going. The idols have changed their names, but they are present more than ever. Inside each one of us, as we will see, there exists one that is the most formidable of all. It is, therefore, worth pausing for a time on this issue as a contemporary issue, and not just as an issue in the past.

The person who made the most lucid and in-depth analysis of idolatry is the apostle Paul. Let us allow ourselves to be guided by him to the discovery of the “golden calf” that lies hidden in each of us. At the beginning of the Letter to the Romans, we read this:

The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of those who by their wickedness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made. So they are without excuse; for though they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their senseless minds were darkened. (Rom 1:18-21)

In the minds of those who have studied theology, these words are linked almost exclusively to the thesis of the natural knowability of the existence of God from the things he has created. Therefore, once this problem is resolved, or after it has stopped being a pressing concern as in the past, these words are very rarely mentioned and appreciated. But the question of the natural knowability of God is, in this context, an issue that is quite marginal. The words of the apostle have much more to say to us; they contain one of those “thunders of God” capable of breaking even the cedars of Lebanon.

The apostle is intent on demonstrating what humanity’s situation was before Christ and outside of him, in other words, the point at which the process of redemption begins. It does not start at zero from nature, but at minus zero because of sin. All have sinned; no one is excluded. The apostle divides the world into two categories—Greeks and Jews, that is, pagans and believers—and he begins his indictment precisely against the sin of pagans. He identifies the fundamental sin of the pagan world as ungodliness and unrighteousness. He says that it is an attack on truth—not on this or that truth but on the original truth of all existence.

The fundamental sin, the primary object of divine wrath, is identified as asebeia, ungodliness. What this precisely means is what the apostle immediately explains, saying that it consists in refusing to “honor” and to “give thanks” to God. In other words, it is the refusal to recognize God as God, not rendering to him the consideration that is due to him. It consists, we could say, in “ignoring God” where “ignoring” here does not mean “not knowing he exists,” but “acting as though he did not exist.”

In the Old Testament we hear Moses crying out to the people, “Know therefore that the Lord your God is God” (Deut 7:9), and a psalmist takes up that cry, saying, “Know that the Lord is God. / It is he that made us, and we are his” (Ps 100:3). Reduced to its central core, sin is a denial of that “recognition”; it is the attempt on the part of a creature to annul the infinite qualitative distance that exists between himself or herself and the Creator and to refuse to depend on him. That refusal becomes embodied concretely in idolatry, in which one worships the creature in place of the Creator (see Rom 1:25). The pagans, the apostle goes on to say,

became futile in their thinking, and their senseless minds were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools; and they exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling a mortal human being or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles. (Rom 1:21-23)

The apostle does not mean that all pagans without exception have personally lived in this kind of sin. (He speaks further on, in Romans 2:14ff., about pagans who are acceptable to God because they follow the law of God written on their hearts.) He means the objective situation in general of humanity before God after sin. Human beings, created “upright” (in the physical sense of erect and in the moral sense of righteous), became “bent” through sin, that is, bent over toward themselves, and became “perverse,” that is, oriented toward themselves instead of toward God.

In idolatry, a human being does not “accept” God but makes himself or herself a god. The roles are reversed: the human being becomes the potter and God becomes the pot that is shaped to his or her pleasure (see Rom 9:20ff). There is in all this an allusion, at least implicit, to the account of creation (see Gen 1:26-27). There it says that God created man in his image and likeness; here it says that people have substituted the image and figure of the corruptible human being for God. In other words, God made man in his image, and now man makes God in his image. Since man is violent, he will make violence a deity, Mars; since he is lustful, he will make lust a deity, Venus, and so on. He is now making God a projection of himself.

“You are the man!”

It would be easy to demonstrate that, in some ways, this is still the situation in which we find ourselves in the West from the religious point of view; it is the situation from which modern atheism got its start with Ludwig Feuerbach’s famous saying, “God did not make man in His image; on the contrary man made God in his image.”[1] In a certain sense we have to admit that this assertion is true! Yes, God is actually a product of the human mind. The issue, however, is knowing which God is being referred to. It is certainly not the living God of the Bible but only a surrogate.

Let us imagine a deranged person today taking a hammer to Michelangelo’s statue of David out in front of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence and then starting to cry out with an air of triumph, “I have destroyed Michelangelo’s David! His David does not exist anymore! His David does not exist anymore!” The poor deluded fellow does not realize that it was only a cast, a copy for tourists in a hurry, since Michelangelo’s real statue of David, because of such an attempt in the past, has been taken out of circulation and is stored safely in the Galleria dell’Accademia. This parallels what happened to Friedrich Nietzsche when, through one of his characters’ words, he proclaimed, “We have killed God!”[2] He did not realize that he had not killed the real God but only a “plaster” copy of him.

We need just a simple observation to be convinced that modern atheism has nothing to do with the God of Christian faith but with a deformed idea of him. If the idea of the one and triune God had been kept alive in theology (instead of talk about a vague “supreme being”), it would not have been so easy for Feuerbach’s theory to prevail, that God is a projection of human beings themselves and of their essence. What need would human beings have had to split themselves into three—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? It is a vague deism that is demolished by modern atheism, not faith in the one and triune God.

But let us move onto something else. We are not here to refute modern atheism or to take a class in pastoral theology; we are here to undertake a journey of personal conversion. What part do we have—I mean “we” in the sense of us believers here—in the tremendous indictment of the Bible against idolatry? According to what has been said up until now, it would seem in fact that more than anything else, we have taken on the role of accusers. Let us hear what follows in Paul’s Letter to the Romans. After having ripped off the mask from the world’s face, the apostle next rips off the masks from our faces as well and we will see how.

You have no excuse, whoever you are, when you judge others; for in passing judgment on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, are doing the very same things. You say, “We know that God’s judgment on those who do such things is in accordance with truth.” Do you imagine, whoever you are, that when you judge those who do such things and yet do them yourself, you will escape the judgment of God? (Rom 2:1-3)

The Bible tells us the following story. King David had committed adultery; to cover it up he had the woman’s husband killed in battle, so at that point taking on the wife for himself could have even seemed like an act of generosity on the king’s part toward the soldier who died fighting on his behalf. This was a real chain of sins here. Then the prophet Nathan, sent by God, came to him and told him a parable (but the king did not know it was a parable.) There was, Nathan said, a very rich man in the city who had flocks of sheep, and there was a poor man who had only one sheep that was very dear to him from which he drew his livelihood and that slept in his house. A guest arrived at the rich man’s house so, sparing his own sheep, he took the sheep from the poor man and had it killed to prepare the table for the guest. When David heard this story, his wrath was unleashed against that man and he said, “The man who has done this deserves to die!” Then Nathan, immediately dropping the parable, pointed his finger at David, said to him, “You are the man!” (see 2 Sam 12:1ff).

That is what the apostle Paul does to us. After having pulled us along behind him in righteous indignation and horror at the ungodliness of the world, when we go from chapter one to chapter two of his letter, it is as though he suddenly turns toward us and repeats, “you are the man!” The reappearance at this point of the phrase “without excuse” (anapologetos), used earlier for the pagans, leaves no doubt about Paul’s intentions. While you were judging others—he concludes—you were condemning yourself. The horror you conceived for idolatry is now turned against you.

The “judge” throughout the second chapter turns out to be a Jew, who is to be understood here more as a type. The “Jew” is the non-Greek, the non-pagan (see Rom 2:9-10). He is the pious man who is a believer, who has strong principles and is in possession of revealed morality, who judges the rest of the world and, in judging it, feels himself secure. “Jew” in this sense is each of us. Origen actually said that in the Church, those who were targeted by these words of the apostle are the priests, presbyters, and deacons, that is, the guides, the leaders. [3]

Paul himself experienced this shock when he went from being a Pharisee to being a Christian, so he can now speak with great conviction and point to the path for believers to come out of Phariseeism. He exposes the peculiar recurring illusion that pious and religious people have of being sheltered from the wrath of God just because they have a clear idea of good and evil, they know the law, and at the occasion they know how to apply it to others. However, when it comes to them, they think that the privilege of being on God’s side—or in any case the “goodness” and “patience” of God they know well—will make an exception for them.

Let us imagine this scene. A father is reprimanding one of his sons for some kind of transgression; another son, who has committed the same offense, believing to win over his father’s sympathy and escape the reprimand, also begins to rebuke his brother loudly, while the father is expecting something else entirely. The father expects that hearing him scold his brother and seeing his goodness and patience toward him, the second son would run to throw himself at his father’s feet, confessing that he too was guilty of the same offense and promising to correct himself.

Do you despise the riches of his kindness and forbearance and patience? Do you not realize that God’s kindness is meant to lead you to repentance? But by your hard and impenitent heart you are storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath, when God’s righteous judgment will be revealed. (Rom 2:4-5)

What a shock it is the day you realize that the word of God is speaking in this way precisely to you, that the “you” is yourself! This is what happens when a jurist is completely focused on analyzing a famous verdict issued in the past that is authoritative, when suddenly, observing it more closely, he becomes aware that the verdict applies to him as well and is still in full force. Suddenly it alters that person’s situation, and he stops being sure of himself. The word of God is engaged here in a genuine tour de force; it turns upside down the situation of the one who is dealing with it. Here there is no escape: either we need to “break down” and say like David, “I have sinned against the Lord!” (2 Sam 12:13), or there is a further hardening of the heart and impenitence is reinforced. In hearing this word from Paul one ends up either converted or hardened.

But what is the specific accusation that the apostle levels against the “pious”? That of doing “the very same things” that they judge in others, he says. In what sense does he mean “the very same things”? In the sense of materially the same? He means this as well (see Rom 2: 21-24), but above all he means “the very same things” in terms of substance, which is ungodliness and idolatry. The apostle highlights this better in the rest of the letter when he denounces the claim of saving oneself through works and thus making oneself a creditor and God a debtor. If you, he says, observe the law and do all kinds of good works, but only to affirm your righteousness, you are putting yourself in God’s place. Paul is only repeating with other words what Jesus had tried to say in the Gospel through the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector in the temple and through numerous other ways.

Let us apply all of this to us Christians, considering, as we said, that Paul’s target is not so much the Jewish people as it is religious people in general and in his specific case the so-called “Jewish Christians.” There is a hidden idolatry that lays traps for the religious person. If idolatry is “worshiping the works of one’s own hands” (see Is 2:8; Hos 14:4), if idolatry is “putting the creature in God’s place,” then I am idolatrous when I put the creature—my creature, the work of my hands—in place of the Creator. My “creature” could be the house or the church that I am building, the family that I am establishing, the son I have brought into the world (how many mothers, even Christian mothers, unconsciously make their son, especially if he is an only child, their God!). It can be the religious institute that I founded, the office that I hold, the work I perform, the school I direct. In my case, this very sermon I am preaching to you!

At the core of every idolatry is self-worship, the cult of self, self-love, putting oneself at the center and in first place in the universe, sacrificing everything else to that. We just need to learn to listen to ourselves when we speak to discover the name of our idol, since, as Jesus says, “Out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks” (Mt 12:34). We will discover how many of our sentences begin with the word “I.”

The result is always ungodliness, not glorifying God but always and only oneself, making even the good, including the service we render to God—and God himself!—serve one’s own success and personal affirmation. Many trees with tall trunks have a taproot, a mother root that descends perpendicularly below the trunk and makes the plant sturdy and unmovable. As long as we do not lay an axe to that root, we can chop off all the lateral roots but the tree will not fall. But that space is very narrow, and there is no room for two: either it is myself or it is Christ.

Perhaps returning within myself, I am ready at this point to recognize the truth that until now I have lived in some measure “for myself,” that I too am involved in the mystery of ungodliness. The Holy Spirit has “convicted me of sin.” Now the ever-new miracle of conversion can begin for me. If sin, as Augustine explained to us, consists in bending toward oneself, the most radical conversion consists in “straightening oneself up” and turning ourselves to God again. We cannot do it during the course of a sermon or during one Lent; we can, however, at least make the firm decision to do it, and that is already, in some way for God, as if we had done it.

If I align all of myself on God’s side against my “I,” then I become his ally; there are now two of us together to fight against the same enemy, and victory is assured. My self, like a fish out of water, can still flop around and wriggle a bit, but it is fated to die. It is not, however, a death but a birth: “Those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it” (Mt 16:25). To the extent that the “old man” dies, what is reborn in us is “the new self, created according to the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness” (Eph 4:24)—the man or the woman that all human beings secretly wish to be.

May God help us always to realize again the true task of life, which is our conversion.

[1] Ludwig Feuerbach, “Lecture XX,” Lectures on the Essence of Religion, trans. Ralph Manheim (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), p. 187.

[2] See Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science #125, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vantage Books, 1974), p. 181.

[3] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans Books 1-5, 2, 2, trans. Thomas P. Scheck, vol. 103, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2001), p. 104; PG 14, p. 873.

_____________________________________

English Translation by Marsha Daigle Williamson