The mention of Satan tends to evoke images of a pitchfork-wielding maniac in a red costume. It’s understandable, as this cartoonish depiction predominates.

However, a number of prominent artists have portrayed Satan in quite a different way. Have you ever seen the hellish icon appearing sensitive and thoughtful? He was, after all, an angel – long ago.

The Bible’s lack of satanic physical description has in a sense facilitated creative expression, as there really are no parameters dictating Satan’s appearance. Thus, artistic license can run free, venturing as far as an artist’s imagination and skill will permit.

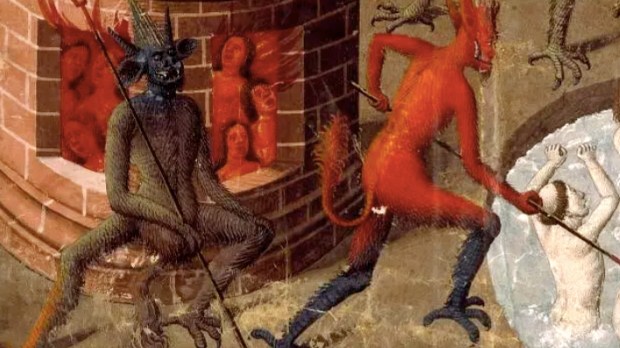

By the end of the Middle Ages, however, a similarity of theme pervaded most every depiction of Satan, whom artists tended to portray as a hideous man-beast, typically relishing torture and depravity. Devils from this period often had horns and other bestial imagery believed to originate from various bygone religious movements in Western Asia.

This beastly devil, which continues to resurface even today, remained the satanic standard into the Renaissance. A 1491 illustrated edition of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy depicts a monstrous Satan with three heads, each of them devouring a human body belonging to Dante’s three arch-traitors: Brutus, Cassius, and Judas Iscariot. Additionally, each of Satan’s hands clutches a terrified human figure, and another trapped human figure is visible due to a hole in Satan’s stomach.

Though Alighieri’s Divine Comedy is sometimes viewed as the finest work of Western literature, it was another epic poem, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, that brought a sea change in satanic portrayals. Milton’s classic imbued the devil with unprecedented psychological depth, and visual artists responded with a wider range of satanic depictions, including the theme of Satan as a tragic soul. He was no longer a nightmarish creature, but a human-like character suffering an endless nightmare.

French artist Gustave Doré’s illustration for a 19th-century edition of Paradise Lost depicts Satan quite literally as an angel just banished from heaven, and making the immense journey downward – forever.

Though a perpetual outcast, Satan is still depicted as having his moments of ecstasy, especially when human beings surrender to temptation. Toward the end of the 18th century, William Blake – the legendary poet who was also a fine visual artist — depicted Satan triumphantly gliding over a prostrated Eve and the coiled serpent that had tricked her.

In the late 19th century, Russian artist Mikhail Vrubel sought to portray a devil that was “not so much evil as suffering and sorrowing.” The fruition of this goal was his “Seated Demon,” a painting that displays a pensive, rather androgynous Satan sitting in a bed of flowers beneath a fiery sky.

The very fact that Vrubel’s “demon” is “seated” makes the subject appear less threatening, at least in the immediate physical sense. This thinking man’s Satan, a soulful pariah painfully aware of his eternal-life-sentence, could not be further removed from the raging monster of past centuries.

Scottish artist Joseph Noel Paton painted a sleeping Jesus watched over by an angel – the fallen angel. Cherubic and eerily calm, this Satan gazes upon the Son of the same God he betrayed. But there isn’t much evident malice, and the milieu is far from hellish, as both Jesus and Satan are situated on the perch of a mountain beneath the dramatic last traces of a setting sun.

A somewhat more active Satan is portrayed in American artist Jerome Witkin’s 1978 painting, “The Devil as a Tailor.” This particular devil is quietly engaged in the task of sewing a Nazi uniform. Appearing towards the end of a 20th century that made vivid display of evil’s frequent banality, Satan was no longer a medieval dungeon master or a tragic antihero. Instead, he had become a working stiff. Such mundane human guise was suitable for a century that witnessed the ascension of Hitler and Stalin. Who needs a horned monster or a winged angel? It had become clear that Satan could manifest in the human form all too well.

The increasingly digital 21st century could lend itself to new artistic depictions of Satan. Perhaps the devil can manifest as a computer virus.

Just as the sacred can elicit people’s devotion, so can the abominable elicit their fascination. As long as such fascination remains, the odds are that Satan will continue to resurface and transform in art – and in life as well.