Tradition and popular devotion have often portrayed Jesus and Joseph as carpenters, working together, sharing both workshop and tools while building chairs, stools, and tables. Even some Spanish Baroque paintings show a very young Jesus with a small wood splinter stuck in his finger, a tiny drop of blood flowing out of it, or carrying a wooden log on his shoulder while in the workshop, as if foreshadowing his later death on the cross. But is that what the biblical text itself actually says? Looking at the original Greek, the Latin translation, and Jesus’ own historical context might answer this question … or not.

Read more:

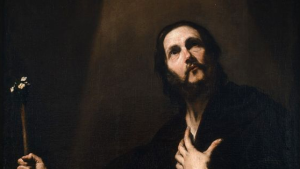

Why is Saint Joseph depicted as an old man in art?

Sure, most translations use the word “carpenter” to describe Jesus’ and Joseph’s trade. But the Greek word we read in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark can be read in many different ways. The word the Gospels use is téktōn, a common term used for artisans, craftsmen, and woodworkers (so, yes, it can translate as “carpenter”), but also, interestingly, it can refer to stonemasons, builders, construction workers, or even to those who excel in their trade and are able to teach others (as in the Italian maestro). The Latin translation we find in the Vulgate, faber, actually preserves the very different meanings the Greek téktōn has. A faber is a general term used for workers and craftsmen in general. A faber can surely work as a carpenter every now and then, but a lignarius is a carpenter by trade.

Professor James D. Tabor, a biblical scholar at the University of North Carolina, has suggested “builder” or “stonemason” would be a better translation for the Greek téktōn in Jesus’ case, for very specific reasons. On the one hand, Jesus’ preaching often uses metaphors inspired by construction: frequent references to “cornerstones” and “solid foundations” might suggest Jesus was indeed familiar with the details regarding how to plan, finance, lay, and build a house. Also, given the fact that the region where Jesus lived and died is not exactly abundant in trees, and that most houses in his day were built with stones, thinking Jesus and Joseph might have worked in the building business makes sense.

But it is not that easy either. In the Septuagint (the very first translation of the Hebrew Bible from Hebrew and Aramaic into Greek), we find the Greek téktōn being used in the book of Isaiah, and also in the list of workmen building or repairing the Temple in Jerusalem in the second book of Kings, to distinguish carpenters from other workers. This distinction was already a classic one, as the Greek already frequently used the word téktōn to refer specifically to a carpenter, using lithólogos for stone worker, and laxeutés for mason. Thinking this common use of the word was inherited by the authors of the Gospels, who were well acquainted with the Septuagint, is only logical.

But comparing the Greek in the Septuagint with the original Hebrew found in Isaiah is also necessary. The Greek téktōn is the word commonly used to translate the generic Hebrew kharash, the word commonly used for “craftsman.” However, téktōn xylon is the verbatim translation of the Hebrew kharash-‘etsim, “craftsman of woods,” that is in fact found in Isaiah 44:13. But the Hungarian bible scholar Géza Vermes suggested it is possible that the Greek téktōn was not translated from the Hebrew kharash but, rather, that it corresponds to the Aramaic naggara. In fact, Vermes argued, when the Talmud refers to someone as a “carpenter,” it might imply a very learned man. This would mean, then, that the authors of the Gospels would be indicating Joseph was in fact a learned man, who was not only wise but also literate in the Torah, regardless of his trade.