Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Hell is described in the Catechism of the Catholic Church as a state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed. Catholic doctrine makes it clear that God predestines no one to go to Hell. Choosing Hell implies a rather willful and persistent turning away from God, a rejection of God’s merciful love. In fact, both the affirmations of Scripture and the teachings of the Church on the subject of Hell are — again, according to the Catechism — “a call to the responsibility incumbent upon man to make use of his freedom in view of his eternal destiny” and, at the same time, a call to conversion. But if Hell is described as a “state,” why is it often depicted as a “place”?

Read more:

A whole course on Dante’s Divine Comedy, from Yale University, is up on YouTube

It is not clear, according to some apologists, if the same notion of Hell we find in the New Testament is present in the Old. The New Testament offers a more elaborate — and explicit — eschatology than the one we find in the Hebrew Bible. However, the Hebrew Bible is not devoid of descriptions of Hell: the Psalmist often refers to God’s “day of wrath” (Ps 110:5) and Daniel describes the duration of this day in terms of “everlasting contempt” (Dan 12:2), making it eternal. Also, Isaiah uses the word Sheol — commonly translated as “Hell” — to refer to either death itself or to “the place of the dead.” When this passage from Isaiah is read next to that of Matthew in which we find Jesus saying “he who does not love remains in death, and anyone who hates his brother is a murderer” (Mt 25: 31.46), an obvious conclusion can be drawn: Hell is without love. But this doesn’t solve the place/state dichotomy we just noticed.

Jesus often speaks of “Gehenna,” following Jeremiah. This word, “Gehenna,” refers to the Valley of Hinnom—the “Ge-Hinnon,” in Tiberian—a small valley in Jerusalem where some of the very early kings of Judah would sacrifice their children by fire. It is only natural that the place was then associated not only with the destination of the wicked but also with an “unquenchable fire.” But we know some other torments, besides fire, have been associated with this loveless place.

Read more:

Why these popes think you should be reading Dante

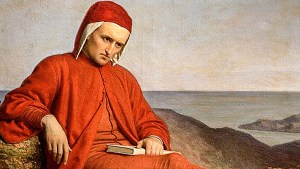

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here,” reads the inscription Dante placed at the gates of hell in his Inferno, the first part of his Divine Comedy. Guided by the Roman poet Virgil, Dante travels through nine circles of suffering within the Earth. That is, he literally goes through hell. In a way, Dante’s journey represents that of the soul towards God, and the Inferno is supposed to depict the recognition, repentance and rejection of sin.

To help you through your journey, an Italian design cooperative called Alpaca, in a joint venture with design studio Molotro, created a tool that, according to the article published by Open Culture, aims to be “a systemic access point to Dante’s literature, aiding its study.” May it serve you as well as Virgil served the poet!