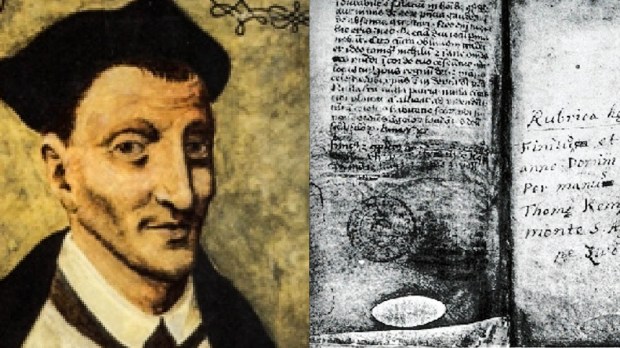

Six hundred years ago, he began writing The Imitation of Christ, which would become among the most widely read and translated books in the Christian world, the go-to for countless saints. And yet rather little is known of the author Thomas à Kempis, who was born “Thomas Hemerken” in the western German town of Kempen in either 1379 or 1380.

At about age 12, he headed to the Dutch city of Deventer to study under the prominent theologian Florentius Radewyns. In that day, Deventer was an epicenter of the “modern devotion” revival that sought to emulate the religious intensity of the earliest Christians. This atmosphere had a huge impact on the young à Kempis, who, along with receiving such devotional influence, established himself as a solid student and an adept copier of manuscripts.

He later joined a nearby monastery, where he would reside during the next seven decades. Ordained a priest in 1413, he continued to devote numerous hours to mentoring novices and copying or composing manuscripts.

Depending on the source, à Kempis started his magnum opus at some point between 1418 and 1420. Written in a simple and direct style, the Imitation is viewed as the archetypal work of the modern devotion movement, which, among other objectives, endeavored to make religion easier to comprehend.

The Imitation consists of four books of spiritual instruction. Its author extols humility as the highest virtue and, as one might imagine, he stresses the spiritual over the material. Though he champions the ascetic life, he recommends moderate asceticism, as opposed to its more extreme versions.

Read more:

Praying for humility when you love compliments

Its popularity was immediate and persistently spectacular: Aside from the Bible, the Imitation was the book most often printed in the 16th century. It had gone through 740 editions by 1650, and 1,800 editions had seen print by the year 1779.

Though some might view the Imitation as geared largely for monastics, it clearly appealed to a far broader audience. Indeed, the book’s appeal was remarkable – and quite possibly unique – in the way it continued to elicit the admiration of persons on both sides of post-Reformation Christianity.

The fourth and final book of the Imitation was completed in 1427. In ensuing years, à Kempis served his monastery in a managerial role. Eventually, though, he was relieved of such duties so he could focus on the writing and contemplation that was more aligned with his talents and personality.

In physical appearance, à Kempis was a man of average height with a dark complexion, wide forehead, and penetrating eyes. He had an affable disposition but a need for solitude that frequently surfaced. When parting from company so he could devote himself to prayer, he was known to say: “I must go: Someone is waiting to converse with me in my cell.”

He rarely spoke about everyday subjects and seemed to have scant interest in them. But when a discussion turned to the spiritual, he was inclined to provide a “ready torrent of eloquence.”

Read more:

A special Advent prayer to maintain a spirit of silence and peace

Thomas à Kempis died on August 8, 1471, when he was in his early 90s. Though his name has remained famous, any biographical details have stayed comparatively obscure. Likely factors for such obscurity are that he lived a devoted but outwardly undramatic life, almost never ventured far from his monastery, survived into very old age, and died in a way far removed from any glorious martyrdom. Additionally, he has never come close to canonization. A 17th-century Bavarian archbishop sought to launch à Kempis’s cause for beatification, but the archbishop died before the cause gained much traction, and no further progress has since been made.

Some 200 years after à Kempis’s death, serious controversy began to arise about the authenticity of his authorship of the Imitation. Several other spiritual writers were credited with the work instead. However, the more the situation was investigated, the likelier it appeared that à Kempis was indeed the author. As of 1910, The Catholic Encyclopedia described him as “completely vindicated” in the dispute over authorship.

A less-resolved point of contention involves the possibility of a mere mortal being able to successfully imitate Christ. However possible this objective may be, one can find it encouraging that so many persons have shown interest in imitating Him. And seeing as how the Imitation has never gone out of print, one must conclude that à Kempis’s masterwork continues to facilitate this noble, albeit challenging, quest.

In commemoration of the Imitation’s 600th anniversary, a special illustrated edition is due for release.

Read more:

What is Jesus doing in the tabernacle? The Bible’s answer