The Word of God is one of the normal, ordinary, and effective means by which the Holy Spirit wishes to teach us to pray.

This Aleteia Series is looking at the signs from John’s Gospel as concrete lessons in prayer, taught by the Holy Spirit Himself.

See the series here:

Read more:

What is Jesus doing in the tabernacle? The Bible’s answer

Read more:

If the Holy Spirit is your teacher, here is his textbook

Read more:

What memory has to do with learning how to pray

Read more:

Have we been putting this off for 38 years?

The fifth sign (John 6:15-24): You might as well pray badly

The fifth sign in the Gospel of John has, as its immediate context, the absence of Jesus: “He withdrew again to the mountain alone” to avoid any attempt by the people to make him into an earthly king. The “again” here is telling: Our Lord did too many good works to count during his time on earth, but he also unapologetically and habitually made time for extended solitary prayer. No doubt familiar with the Lord’s penchant to sometimes pass whole nights in prayer, the disciples went ahead and embarked in a boat without him. They intended to cross the Sea of Galilee for Capernaum, perhaps to seek shelter for the night.

But as the Evangelist tells us, this was no pleasure cruise: It was dark, and “the sea was stirred up because a strong wind was blowing.” The disciples had to row in these rough waters, and it must have been slow going.

The disciples had been rowing some three to four miles in these conditions when they saw Jesus walking on the sea, coming toward them. It was at this point that “they began to be afraid.” Yet Christ reassures them, “It is I; do not be afraid.”

The sign then concludes with what seems to be another minor miracle: The disciples wished to take Jesus into the boat at that point, but instead “the boat immediately arrived at the shore to which they were heading.”

Note that the familiar detail of Peter briefly walking on the water toward Jesus is omitted in this account. John selects only those details of the miracle relevant to his immediate purpose of showing forth the divinity of Christ. Mastery of the sea is certainly a sign of divine power in the Scriptures. Our Lord’s greeting to the frightened apostles—“It is I”—could also be rendered as “I am,” one of God’s characteristic ways of speaking of himself in the Scriptures.

Read more:

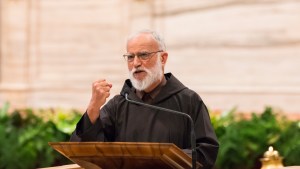

Fr. Cantalamessa’s 1st 2018 Advent sermon: God IS!

While this sign’s immediate purpose may be to show us the divinity of Christ, I would also suggest that a more apt image for the daily “grind” of personal prayer can scarcely be imagined. We often feel that we don’t know what we are doing, that all our efforts are somehow opposed, and that gains are either nonexistent or painfully incremental. We are quickly tempted to abandon our efforts.

However, that final moment in this sign, that strange and immediate arrival at the destination, provides us with a corrective to these feeling of despair. After all the effort, all the mess, and all the uncertainty, Christ arrives, and the goal is suddenly achieved.

Ultimately, why do we pray? To be sure, we have lots of little requests that we wish God to grant, but what is the goal of prayer more generally? This fifth sign suggests a good answer: being in the presence of Christ. We may be in his presence asking for help, or apologizing for our misdeeds, or thanking him, or praising him—but in all cases the more fundamental goal is one of presence: us to God, and God to us.

If, as the Catechism says, “the life of prayer is the habit of being in the presence of the thrice-holy God and in communion with him,” then I suggest a somewhat startling conclusion: Praying “badly” may not be the deal-breaker that we often imagine it is.

Allow me an analogy to family life: a child sitting quietly next to me reading a book may not capture my attention half as well as a child who is clearly struggling to read, sighing loudly, flopping around on the floor in exasperation, etc. The very helplessness of the struggling child calls me to be more “present” as a father than I might otherwise be, much in the same way the struggles of the disciples brought Christ across the waves to their boat.

Read more:

Pope confesses he shares Therese’s weakness, sometimes sleeps in prayer

Of course we should not wish to be “struggling children” or “floundering disciples” during our times of prayer. We should strive to pray with attention and devotion. But if the choice is between praying badly and not praying at all, then we might as well pray badly. Even our distracted, theologically uniformed, and inconsistent efforts at prayer can help us achieve the “destination” that is Christ himself. Praying badly is still an appeal to Christ, especially to his mercy.

Read more:

Why anything worth doing is worth doing badly