In the United States especially, the words “Anglo-Saxon” tend to be sandwiched between “white” and “Protestant.” As the exhibition Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War shows, the reality is quite different from the buttoned-up, exclusive and insular modern tribe that is associated with the more ancient tribal grouping.

This exhibition at the British Library in London reveals much about the true nature of Englishness at a time when the concept is receiving a lot of attention; the nation’s divorce from the rest of Europe is drawing nearer. The first myth to be tackled is that the Anglo-Saxons were hearty ale-swiggers with no regard for their Continental cousins. There is still a belief that they were even going their own Anglican way, long before King Henry VIII officially split from the Church of Rome.

Instead, the exhibition makes it clear that the Anglo-Saxons were highly attuned to Europe. They were tribes who took over much of Britain after the Romans had left, pushing the original Celtic inhabitants to the fringes. Their connection with the Continent never ceased. Nor were they seen as illiterate hillbillies by the Church of Rome.

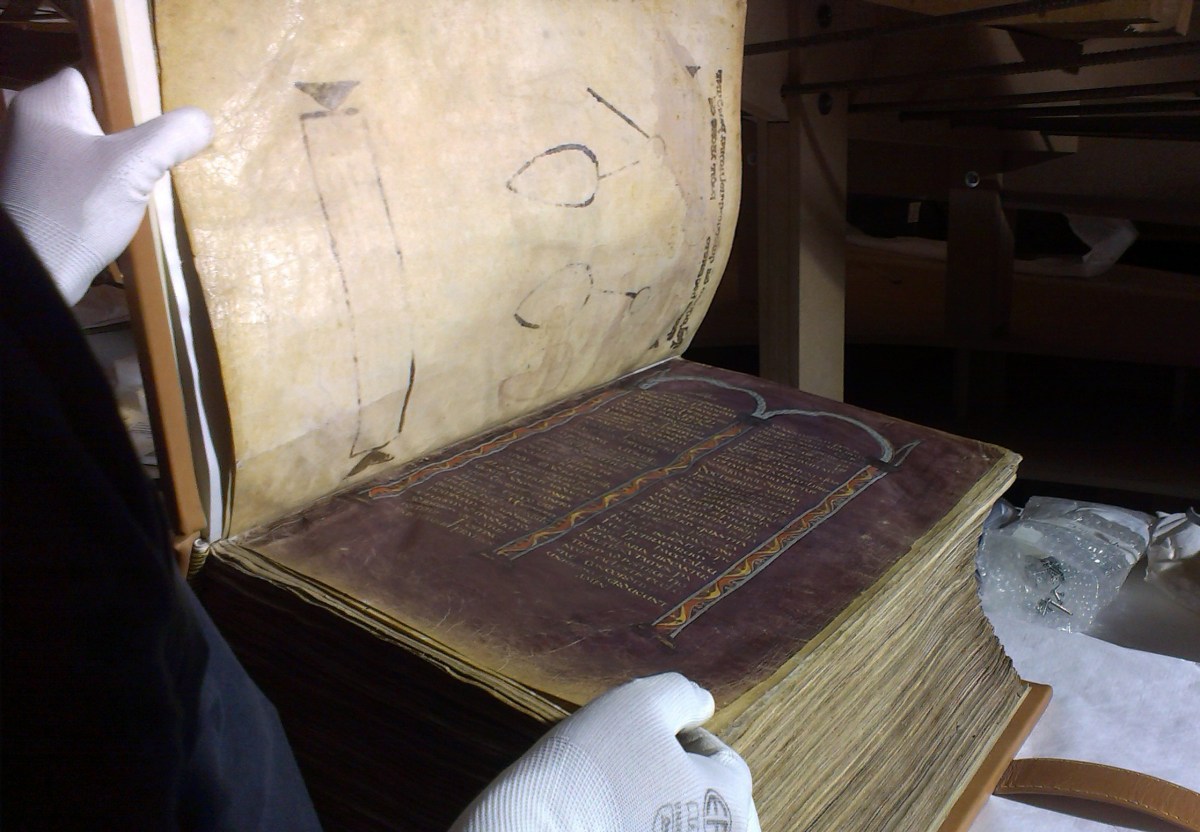

The Codex Amiatinus

One of the most revealing items in the exhibition is the Codex Amiatinus, the earliest single-volume Latin Bible known anywhere in the world, and featured in Aleteia on October 22. If visitors fail to be impressed by its age (one thousand three hundred years) or its size (75 lb.), its refinement goes well beyond expectations of the so-called “Dark Ages.” This is not a term you will see much in this exhibition.

The English were a literary crowd, even then. Inevitably, considering that it is a library, the British Library is focusing on the written word. There was more than this in the past, but not much of it remains. Some of the finest works are at this exhibition.

The Alfred Jewel

Even when an object may not be obviously related to books, sometimes it is. The most famous example is an Anglo-Saxon treasure known as the Alfred Jewel. After centuries of conjecture about the sort of jewel this gold and enamel item might be, the scholarly consensus is that it’s a book pointer. Previously thought to be a pendant or part of a crown, it seems to have served a more literary purpose. Similar to the way Jews read the Torah, the Alfred Jewel was probably attached to a stick and would then glide across the page. The Anglo-Saxons knew how to handle a book properly. It might have been a page turner, too. If only the unfortunate monks in The Name of the Rose had done the same they would have lived. Licking fingers to turn pages is still a nasty habit, 700 years after Umberto Eco’s book was set.

The best thing about the Alfred Jewel is that it does not show King Alfred in majesty, as my generation of schoolchildren in England were taught. It is more likely to be Christ enthroned, accompanied by the inscription “Alfred ordered me to be made.” Alfred was not just a nation builder and the only English king to be known as “Great,” he was also a devout Christian, none of which prevented the page pointer from lying in a field for centuries, to be discovered in 1693.

Christian symbols from Anglo-Saxon England

There are more obvious Christian symbols on display too. Jewels in the form of a Cross were popular among those who could afford them. Most have been melted down or lost. One of the most striking of these is a gold cross with a garnet at its center. Conservators have resisted the temptation to bend the arms of the cross back into place.

There are very few survivors in precious materials. Crosses have been discovered but crucifixes in Anglo-Saxon times were very rare indeed in any part of the Christian world. They are depicted in some of the manuscripts that proliferate in this exhibition, but the most vivid use is on the cover of the Judith of Flanders Gospels. The text is Anglo-Saxon, from the early 11th century, while the astonishing binding is from Flanders or Germany towards the end of the 11th century.

The Ruthwell Cross

The Anglo-Saxons, like some later Englishmen, valued the written word over the physical representation of Christ. One of the most telling – and visual – items on display is a 3D re-creation of the Ruthwell Cross monument. Although these are often called Celtic crosses, this 8th-century type is from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria and is filled with stories from the life of Christ. The flight into Egypt is depicted with great charm, but where is the Crucifixion? It is there, at the bottom of the stone cross, so weathered as to be almost invisible and probably added much later. This didn’t stop it being considered idolatrous and destroyed in the 17th century by Presbyterians. Part of the 18-foot monument ended up as a bench until it was reassembled in the 19th century.

The Lichfield Angel

The rarest of all survivors is the Lichfield Angel. Discovered as recently as 2003 during building work at Lichfield Cathedral, it shows how advanced Anglo-Saxon stone carving was. As the angel is thought to be the Archangel Gabriel, there is the exciting possibility that excavations at the cathedral might unearth a figure of the Virgin Mary as well. It is a miracle that the stone angel survived both time and iconoclasm. As part of the Annunciation, it makes a seasonal introduction to the Christmas story.