Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

This past week, churches and other institutions around to world have been observing Courage in Red Week, to draw attention to the plight of persecuted Christians. Some buildings and landmarks have been bathed in red light in a campaign promoted by Aid to the Church in Need and Christian Solidarity Worldwide to shed light on the issue.

In the greater New York City area, one woman has been carrying out her own project of illuminating the ongoing challenges to religious freedom. Portrait artist Andrea K. Schneider has turned her attention to the Christians of the Middle East in an exhibit, “Portraits of Faith,” that has been displayed in a variety of venues.

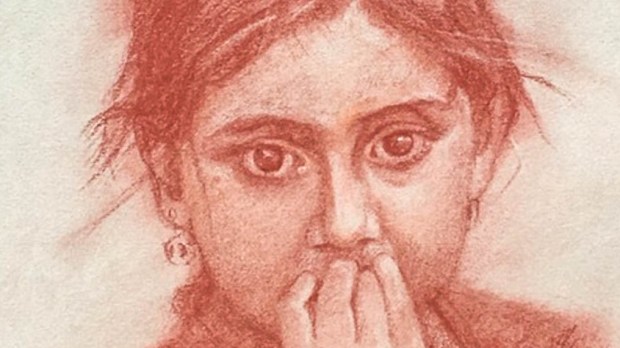

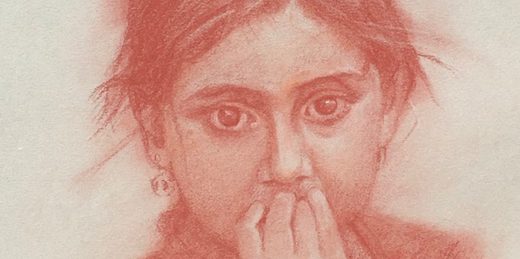

It all started with a face. During a talk at Schneider’s parish in New Jersey, international religious freedom advocate Nina Shea mentioned a three-year-old girl from Erbil, Iraq, Christina, who had been kidnapped from her Christian home and was recovered three years later. Intrigued by the story and curious to know what the girl looked like, Schneider searched the internet and found a photograph of Christina and her mother.

“That face of her mother—just totally distraught over a lost daughter—I could really relate to her as a mother,” Schneider said in an interview. “She was holding a picture of her daughter with her identification papers.”

The Islamic State group was terrorizing Christians and Yazidis in Iraq and Syria, but now it took on a deeper meaning for Schneider, not another story on the news. She read up on the history of Christianity in the region and was appalled that the jihadists were trying to “destroy the culture and civilization” and even “erase the memory” of a people whose roots in the country go back to the very early days of Christianity.

Meanwhile, Schneider, a lifelong artist who has taught art in Catholic schools, was honing her skills in portraiture, which she has always found challenging. She applied for a mentorship with the Portrait Society of America, and as part of the application process she submitted drawings executed from photos of Christina and her mother, and another called “Mother and Child of the Nineveh Plain.” The society gave her the green light to expand on the project, and Schneider traveled to Michigan to do live portraits of recent immigrants who had suffered in Iraq because of their faith.

Joseph Kassab, founder and president of the Michigan-based Iraqi Christians Advocacy and Empowerment Institute, arranged for Schneider to meet with people who had come to the U.S. with refugee status.

“I met people who went through quite a bit,” she said. “They told me that they waited in Turkey for three years to get refugee status, to come to the United States.” Some of them had been told by ISIS that they either had to believe in Islam or be killed. “That was very powerful to me.”

The resulting 12 portraits were featured at a Manhattan symposium marking the 20th anniversary of the U.S. International Religious Freedom Act this fall.

In addition to Christina, Schneider drew a “sweet, young little girl,” who was born in Iraq and who came through Turkey with her mother and brother.

“She was my biggest challenge to draw on an emotional level and to try to capture” her innocence, she said. “All I could think of was what could have happened to her.”

After framing the portrait, she decided to paint onto the overlying glass a red Arabic letter “nun,” which corresponds to the Latin letter n. It was the letter that ISIS painted on the captured homes of Christians, standing for the word “Nazarene,” or Christian, indicating that the houses were up for grabs by the incoming citizens of the caliphate.

In fact, that is what happened to this girl’s house.

“So many people asked me what it means, and I was able to share with them the significance of that,” Schneider said. “Many people said, ‘Oh! That’s like the Jews [in Nazi Germany].’ People didn’t know about it. It became part of the conversation.”

Kassab, who came to the United States from Iraq many years ago, is also a subject in the exhibit.

“Andrea did a great job,” he commented. “She is very meticulous in her work. Through the drawings, she manages to portray me and my colleagues reflecting the agony and sadness in our tired faces due to the horrible atrocities and genocide inflected on our people, the Christians of Iraq that we helped. We are grateful for her work.”

The exhibit will run from December through January at St. Mary’s Abbey-Delbarton School, a Benedictine boys’ school in Morristown.

For more information: www.andreakschneiderart.com