The start of the Renaissance in the 14th century marks a shift in art production compared with the late medieval period. A renewed interest in classicism, an attention to nature and a more individualistic vision of man start to permeate paintings, sculptures, architecture, music, and literature, first in Italy and then around continental Europe. One of the most important revolutions in religious art is the deep emphasis on Jesus’ “humanitas” (Latin for “humanity”). Medieval and Byzantine artists were more interested in highlighting the divine aspect of Jesus and other religious figures, while from the start of the Renaissance onward, the focus shifts to their “humanity.”

This new emphasis is especially evident in the ways artists were depicting the Crucifixion, which, in line with Franciscan philosophy, was seen as the ultimate symbol of Christianity: being willing to give up one’s life to embrace God’s will.

That’s why Renaissance crucifixes started to take on the kind of “dramatic” tone that could already be observed in some of Giotto’s works a hundred years before. Sculptors were interested in evoking empathy towards the human represented on the crucifix rather than reverence for the divine.

By taking a look at three crucifixes by Florentine sculptor Donatello, crafted in the 15th century, we can see how the concept of “humanitas” started to play out in early Renaissance religious art.

Donatello’s Crucifix, Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence

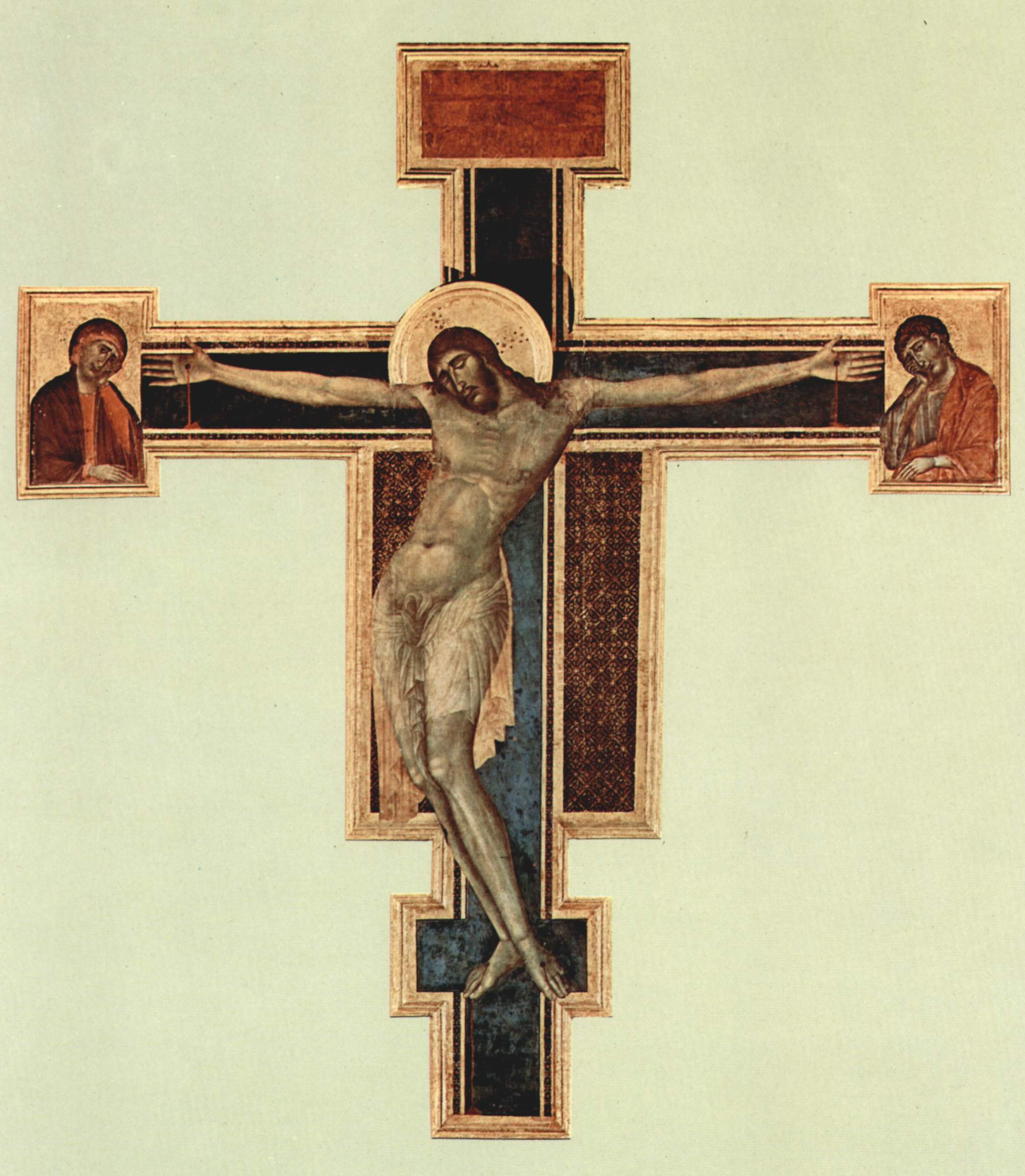

Dated to 1406-1408, this wooden crucifix is preserved inside the Bardi di Vernio Chapel of Florence’s Basilica of Santa Croce. In order to fully grasp the innovation brought forward by Donatello, it’s useful to compare his work with a crucifix by Cimabue, a late medieval artist, displayed in the same church.

Cimabue’s crucifix can be considered a hybrid of Byzantine art, more interested in the divine than the human, and Renaissance art, more interested in the human rather than the divine. Cimabue follows the classic Byzantine canon of sacred art. Christ is depicted more as an “image of God” than as a mortal person. Yet, we see some effort to “humanize” Jesus, for instance by the effect of transparent cloth that shows Jesus’ wounded body.

Donatello takes this concept to the next level. His Santa Croce crucifix is the depiction of a suffering man, rather than a divine abstract. Christ is depicted as a bearded, bulky man who is bleeding. Indeed, Donatello’s stylistic choice was mocked by some of his contemporaries, including “rival” painter Brunelleschi, who accused him of portraying a “peasant” on the cross. But that was precisely what the Florentine sculptor was trying to do: triggering profound empathy among believers by stressing the similarities between Jesus and themselves.

This objective was pursued through vivid realism and by making the sculpture “movable” so it could be taken down from the cross and used during the celebration of Holy Week. Donatello used pegs on the underarms to make arms movable, an innovation that would not have been tolerated during the Byzantine period. This way, his work becomes not just “figurative” but also “performative.”

But Donatello does not completely lose the focus on the divine aspect of Christ. Rather, he mixes elements of human suffering—blood running down from the crown of thorns—with perfectly sculpted features such as the arms and legs. This way he represented the co-existence of God and man in the figure of Christ.

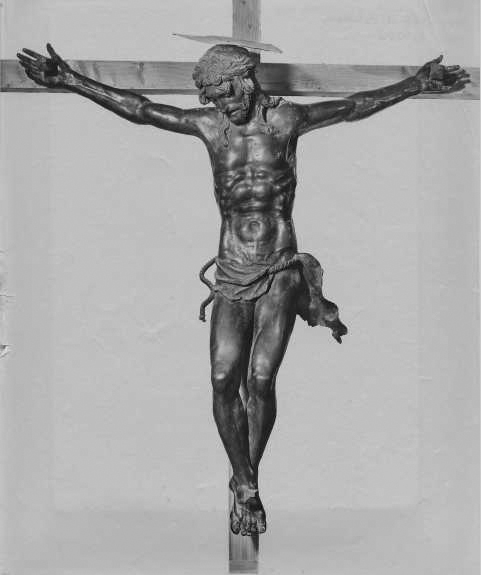

Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua, Padua

Compared with the crucifix of Santa Croce, we can see a more accomplished “harmonization” between the human agony of Jesus and his divine beauty in this bronze crucifix completed by Donatello between 1444 and 1447.

The Santa Croce crucifix presents both elements but stresses the agony more than the divine. Here, both aspects are emphasized equally. The divine is underlined by both “external” elements—the aureola—and “intrinsic” elements—a return to the perfect harmony of proportions typical of Classical sculpture. As explained by art historian Giulio Zennaro, the height of Jesus in this sculpture is equivalent to the width of his arms, a reproduction of the “perfect man” of Vitruvius—a man whose proportions fit perfectly within a square—that was later popularized by Leonardo. The suffering is mostly evident in Jesus’ face but almost invisible in the perfectly sculpted details of his body, something that was made possible by the plasticity of bronze. In a way, Donatello seems to suggest that the perfect integration of the human and divine aspects of Christ is in itself a manifestation of God’s will.

Saint Mary of the Servants Church, Padua

This crucifix has been definitively attributed to Donatello in 2008 thanks to the work of Marco Ruffini, a Professor of Art Criticism at La Sapienza University in Rome. The hypothesis had lingered since 1550, when someone wrote a note saying “he also did the crucifix of the Church of the Servants in Padua” next to a section about Donatello in the famous art history volume by Giorgio Vasari. But it was Ruffini who eventually managed to confirm the attribution by cross-checking historical documents and stylistic analysis.

In this work, Donatello continues his effort to underline the human suffering of Jesus by featuring realistic details like blood, wounded skin and the crown of thorns. It’s almost as if he attempted to condense into a single sculpture all of the suffering endured by Christ since he was captured. Even the choice of a “slim body” rather than a more bulky one seems to be driven by this thirst for realism—that’s what Jesus likely looked like after being imprisoned and tortured by Roman officials. The strive for realism goes even a step further: Christ appears to be fully naked, something that was imposed on crucified “criminals” by Romans. Here Donatello seems to really underline the paradox of the humiliation imposed by mortal humans onto the Son of God. This crucifix is also known as “the crucifix of miracles” because on February 5, 1512, it started bleeding for a total of 15 consecutive days. The miracle happened again on Good Friday and Easter Sunday, this time in front of many people, earning the cross its name “crocifisso miracoloso,” literally “miraculous crucifix.”