Two years ago, the Vatican Museums shipped some of its more outstanding works of art to Moscow, where they were showcased at the State Tretyakov Gallery in an exhibition titled “Roma Aeterna: Masterpieces of the Vatican Pinacotheca – Bellini, Raphael, Caravaggio.” It was the first time in the 500-year history of the Vatican Museums that as many as 42 works of art, ranging from the 12th to the 18th centuries, were sent off in one single exhibition. Needless to say, it was a great success.

Now, Moscow is returning the favor by sharing the works of some of the most important paintings and icons from the renowned Tretyakov Gallery to Rome. The exhibition, titled “Pilgrimage of Russian Art: From Dionysius to Malevich,” opened on November 20 and will continue through February 16, 2019, at the Main Building of the Braccio di Carlo Magno, in the Vatican Museums’ gallery of Bernini’s colonnade. Pope Francis himself visited the museum on November 27, and according to a report by the Russian news agency TASS, told the director of the Tretyakov Gallery giving him a tour that he had never seen such “powerful and meaningful” paintings.

The aim of the exhibition is to parallel the great success of the Vatican exhibition in Moscow both in terms of scope of works and diversity of styles. Instead of following a chronological order, the curators opted for the juxtaposition of works belonging to two main areas of Russian art: early Russian art, such as “The Epiphany (Baptism)” and the works of 19th and 20th century masters, such as “The Apparition of Christ to the People” by Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov.

Thanks to this arrangement, viewers will be able to grasp the differences and similarities between icon-painting in the 15th century and art from the 19th and 20th centuries. These two epochs are in fact divided according to the rule of Peter the Great, used by Russian scholars to divide Russian history into pre-Peter and post-Peter times. Yet, as the exhibition proves, some aspect of Russian art have remained constant throughout the centuries, such as the transposition of Gospel stories on canvas, the emotional intensity of both human and godly figures and certain types of chromatic arrangements.

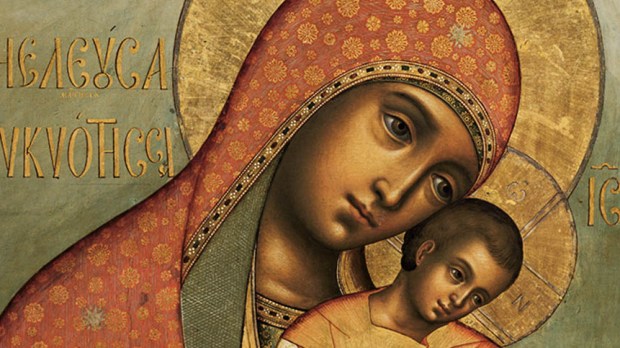

For example, the 15th-century icon “Theotokos Kikkotissa” by S. Ushakov is juxtaposed against the 1888 painting “Life Is Everywhere” by Nikolay Yaroshenko. Both works of art display a similar arrangement of subjects (both have small children looking down at the center of the scene) and matching color scheme of blue/green and red/brown shades.

Another remarkable similarity can be observed in the only set of portraits featured in the exhibition, a portrait of great Russian author Dostoevsky (“Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky” 1872) by Vasily Perov and a portrait of Jesus by Ivan Kramskoy (“Christ in the Wilderness” 1872). Both subjects, pictured as they look down in a reflective pose, display strikingly similar emotional states.

In addition to Dostoevsky and Russian icons, two great symbols of Russian culture, there are other quintessential Russian motifs featured in the exhibition, such as hermits, priests, God’s fools and travelers, all whom played and still play an important role in Russian spiritual culture.

Both the Vatican exhibition in Russia and the current exhibition in Rome were discussed during Pope Francis and Vladimir Putin’s meeting in 2013 and have been realized thanks to the support of Alisher Usmanov’s charity foundation “Art, Science and Sport.”