Many people recognize that a sure path to falling more in love with Jesus is falling in love with his Mother.

And the sure path to falling in love with Mary is getting to know her; there are few tools better for that than a recently released book from Penguin Random House by Brant Pitre: Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary.

In 240 pages, Professor Pitre offers an easy-to-undersand style that more than once will have readers saying, “Wow! But, how did I not know that?”

Aleteia asked Pitre about a few of the sections we found most compelling (and we think this book is a must-have for the coming season!).

I’d like to start our conversation echoing something you say in the book: How is it possible I didn’t know so much of this stuff!?

In that context comes my first question: Would you say that your interpretation of Scripture is largely up for debate? Or is this simply a careful reading with clear conclusions that just haven’t made it into mainstream Catholic awareness (or have been lost to it)?

Pitre: In my experience, many Protestants are familiar with what the New Testament says about Mary, but they are unfamiliar with how Mary is prefigured in the Old Testament. Over and over again, Protestant books on Mary—of which there are very few—ignore the Old Testament background of Mary’s portrait in the New Testament.

Likewise, many Catholics are familiar with what the Church teaches about Mary—for example, that she was sinless, that she remained a virgin her whole life, that she was assumed into heaven—but they aren’t sure where those doctrines come from in the Bible. Over and over again, Catholic books on Mary—of which there are very many—focus on the later Church teachings without ever connecting those teachings to the Bible as a whole.

In Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary, I tried to bring both of these together and show that the key to understanding Catholic beliefs about Mary is to look at what the New Testament says in the light of the Old Testament and ancient Jewish tradition. Once you begin to see Mary through ancient Jewish eyes, you realize she is not just the mother of Jesus. Mary is the new Eve, the new Ark of the Covenant, the new Queen Mother, and so much more.

Of course, biblical interpretation is always “up for debate.” However, in every chapter, I make sure to show that my interpretations are not anything new, but go back to how ancient Christians interpreted what the whole Bible says about Mary.

One of the most fascinating chapters for me was when you led us through an extension of Jesus’ family tree. It seems we know about at least one of Our Lord’s uncles! A specific question in this line, however. Does the Greek have the “comma problem” that English has? By that I mean, when we read about those at the foot of the cross, depending on if we use commas or semicolons, we might come to differing conclusions about how many people the Evangelists specifically mention. Is that issue resolved in the original language?

The chapter on Mary’s perpetual virginity was one the most exciting for me to write. In my experience as a professor, this is one of the most difficult teachings for many Christians to accept (including some Catholics). After all, when the New Testament mentions the “brothers of Jesus” (Mark 6:1-3), isn’t it obvious that Mary had other children?

Now, most Catholics have heard that in Hebrew and Greek, the word “brothers” can mean “relatives” or “cousins.” And that is true. But what most people don’t know is that the Gospels themselves tell you that two of the so-called “brothers” of Jesus—“James and Joses”—are the children of a different woman named “Mary,” who was present at Jesus’ crucifixion (Mark 15:37, 40-41).

Elsewhere, this same woman is “Mary the wife of Clopas” and “sister” of Jesus’ mother (John 19:25). In the original, it is a bit unclear whether there are three or four women at the foot of the Cross—there are no commas in ancient Greek! Nevertheless, we know from ancient Church history that “Clopas” was the brother of Joseph—in other words, Jesus’ uncle.

In short, the New Testament itself gives us plenty of evidence that the so-called “brothers” of Jesus were in fact the children of Clopas and another woman named Mary—not the children of the Virgin Mary. In other words, they were his cousins.

Read more:

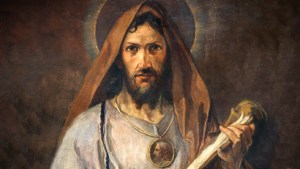

Was St. Jude the one getting married in Cana?

I really enjoyed the section on Rachel. We need to add “Rachel” to our Aleteia list of Marian names! Could you speak a little about Rachel’s role as intercessor and how this is spelled out so clearly in the Old Testament (and how this should make our Protestant brothers and sisters more accepting of the saints praying for us)?

I’m glad you liked that chapter! It’s something you won’t find in most books on Mary.

In the Old Testament, Rachel is the wife of Jacob, the father of the twelve tribes of Israel. She dies in childbirth near Bethlehem (Genesis 35:16-20). Centuries later, the Bible depicts “Rachel weeping for her children” as the Israelites go into exile (Jeremiah 31:15). This led to the later Jewish tradition that, even after her death, Rachel continued to watch over and pray for the Jews as her own children. To this day, Jews visit Rachel’s tomb, and some even ask for her intercession.

As I show in the book, there are several striking parallels between Mary in the New Testament and Rachel in the Old Testament. Mary is a new Rachel, the mother of the Church, who continues to pray for her children on earth, just as Rachel prayed for the children of Israel.

Read more:

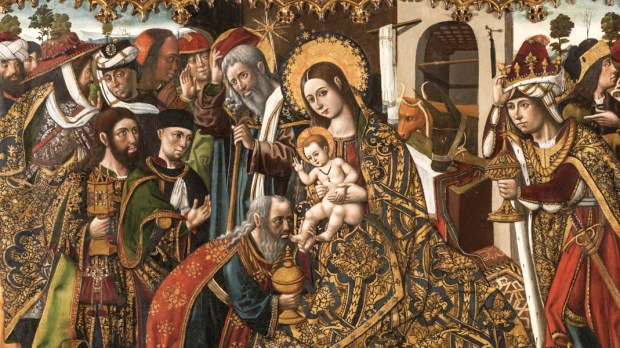

The 9 oldest images of Mary

Conversely, one part of the book that I was disappointed to read was about Mary not having pain in childbirth. As a mom, that’s something I wanted to share with her, I guess. Why do you think God spared her pain at that moment, when he allowed so much pain in the rest of her life, and especially at the cross?

In order to understand the ancient Christian belief in Mary’s painless childbirth, the most important thing to remember is that it was the fulfillment ofan Old Testament prophecy of a “woman” who gives birth without labor “pain” (Isaiah 66:7-8).

From an ancient Jewish perspective, the absence of birth-pangs was a sign that the time of the Messiah had come, and that God was undoing the effects of the Fall of Adam and Eve, such as pain in childbirth (Genesis 3:16). It was a sign that the birth of Christ was the beginning of a new creation.

Ancient Christians also believed that Mary was spared the pain of childbirth because she would not be spared the pain of watching her Son die on Calvary. In fact, Jesus himself compares his crucifixion to the “sorrow” of a “woman” giving birth (John 16:20-22), and then addresses Mary as a “woman” when he gives her to John on the Cross (John 19:25-27).

In other words, it is precisely through the “birth pangs” of the Cross that Mary becomes the mother, not only of John, but, as the book of Revelation says, of all who believe in Jesus (Rev 12:17).

That is why I wrote this book. So that everyone can hear Jesus speaking his last words to them personally: “Behold, your mother” (John 19:27).

~

Purchase here.

And read Professor Pitre in Aleteia below:

Read more:

A Jewish perspective on the queen of all these saints we’re celebrating