In the year 285, the Roman Empire split up into two parts: the Western part, with Rome as its capital, and the Eastern part, with Constantinople, also known as Byzantium, as its capital. That’s why in the following centuries, religious art from the Roman Empire, which adopted Christianity as its official religion in 300, developed along two parallel trends. Christian art produced in Rome maintained its interest in naturalism, while art produced in the Eastern part of the empire focused more heavily on mysticism, adopting some key aspects of Hellenistic style and iconography.

Mosaics are probably one the best examples of how Hellenistic practices were included in what became known as Byzantine Christian art. The technique of creating portraits out of tiny pebbles was first invented in Mesopotamia during the 3rd millennium BC and became widely diffused in ancient Greece, where the tessera technique was developed in 200 BC. Thanks to the technique, it was not just tiny pieces of natural pebbles that could be used to make mosaics but also finely cut fragments of marble and limestone, known as tesserae.

During the Byzantine period, craftsmen started to widen the materials that could be turned into tesserae, including gold and precious stones. According to 1st century architect Vitruvius, the ideal foundation of a mosaic was made of four layers. The first layer, called statumen, was composed of large chunks of bricks or pottery. The following layers, known as rudus, were made of a thick mix of rubble and lime. The third layer, or nucleus, was made using a mix of lime and tiny brick pieces. The last layer, on top of which the tesserae would be laid, was made of a finer mix of crushed lime and brick powder.

On this moist surface, mosaic artists would then proceed to incise guidelines that would later contain different tesserae, using tools like strings, nails and calipers. In order to create tesserae, artists used a hammer and a chisel-like blade set to carve the tiny pebbles out of a block of material. Thanks to their wise use of these tools, anything from marble to glass could be turned into finely shaped pieces that could fit the guidelines marked into the base.

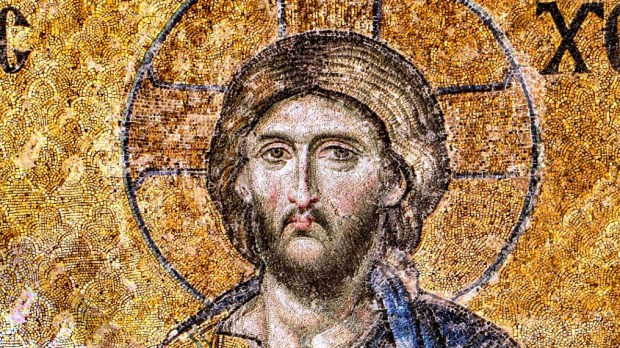

The end result were glittering works of art whose aura attempted to capture an ethereal and spiritual realm. Click on the slideshow to view some of the most striking works of mosaic art from the Byzantine period.