The membership of the International Astronomical Union has voted to recommend that the name of a Belgian Catholic priest be added to the astronomical law explaining the expansion of the universe, or “Big Bang.”

Using an electronic voting system, the IAU passed a resolution to recommend renaming the “Hubble law” as the Hubble–Lemaître Law.

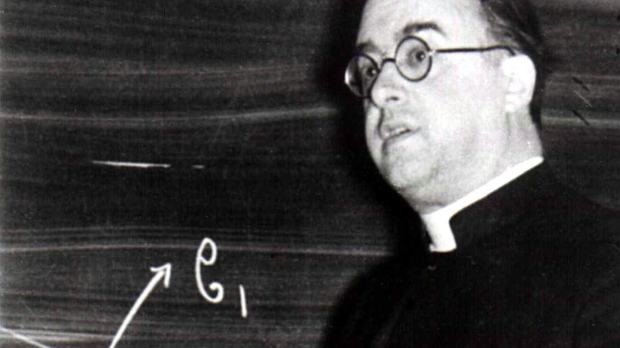

The law had been named after American astronomer Edwin Hubble, although Fr. Georges Lemaître, a Belgian astronomer and priest, in 1927 first discovered the expanding universe—which also suggests a “Big Bang,” according to Science.

“The Hubble–Lemaître law describes the effect by which objects in an expanding Universe move away from each other with a velocity proportionally related to their distance,” said a press release from the international society. “To acknowledge the scientific contributions of Belgian astronomer Georges Lemaître to the scientific theory of the expansion of the Universe, … the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has decided to recommend the Hubble law to be renamed as the Hubble–Lemaître law.”

Fr. Lemaître published his ideas two years before Hubble described his observations that galaxies farther from the Milky Way recede faster. The Hubble Telescope is named for him.

The IAU said that the resolution to suggest renaming the Hubble law was presented and discussed at its General Assembly in Vienna, Austria, in August. The electronic vote, open to over 11,000 members, concluded October 26. More than 4000 members voted, and 78 percent cast a yes vote.

Science explained the background:

In 1927 Lemaître calculated a solution to Albert Einstein’s general relativity equations that indicated the universe could not be static but was instead expanding. He backed up that claim with a limited set of previously published measurements of the distances of galaxies and their velocities, calculated from their Doppler shifts. However, he published his results in French, in an obscure Belgian journal, and so they went largely unnoticed. In 1929, Hubble published his own observations showing a linear relationship between velocity and distance for receding galaxies. It became known as Hubble’s Law. “Hubble was clearly involved, but was not the first,” says astronomer Michael Merrifield of the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. “He was good at selling his story.”

Helge Kragh, a historian of science at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, charged that the background notes presented to IAU members was “bad history.” The text of the resolution asserts that Hubble and Lemaître met in 1928, at an IAU general assembly in Leiden, the Netherlands—between the publication of their two papers—and “exchanged views” about the theory, Science explained. Kragh maintains that meeting “almost certainly didn’t take place.”

But historians know from comments from Hubble’s assistant that he returned very excited from Leiden and began to gather more data, according to Piero Benvenuti of the University of Padua in Italy, who proposed the change of name.. “Who else could have talked to Hubble about this problem but Lemaitre?” asked Benvenuti, who stepped down as IAU general secretary in August.

Science reported that Benvenuti’s proposal has come under fire for confusing two different issues: the expansion of the universe and the distance-velocity relation for galaxies, which is also known as the Hubble constant. Hubble never claimed to have discovered cosmic expansion, but did do much of observing work to nail down how fast the universe was expanding.

“If the law is about the empirical relationship, it should be Hubble’s Law,” Kragh said. “If it is about cosmic expansion, it should be Lemaître’s Law.”

Asked about who would have the final authority to rename the law, Benvenuti, in an email to Aleteia, said, “Similarly, you may ask yourself who had the authority to name the Hubble Law in the first place.”

Benvenuti said the resolution recommends the use of the new name “on the basis of indisputable historical fact (e.g. the 1927 Lemaître paper).” The IAU represents the largest international community of professional astronomers,” he said. “If it express a clear will (78% votes in favor) to make a recommendation about one of the pillars of modern astronomy/cosmology, I believe the recommendation has enough moral authoritativeness to be listened to.”

“The fact that more than 3000 professional astronomers agreed (some of them enthusiastically) on the new name means that future generation of astronomers will, at least, be [reminded] about the main contributors to the construction of model cosmology,” Benvenuti said.