Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

If you were a woman who gave birth to a premature baby weighing between two and three pounds during the early 1900s, your best odds of saving your child’s life weren’t by taking it to a hospital. Instead, you had to go to a sideshow in Coney Island or Atlantic City and look for the exhibit run by Dr. Martin Couney and his staff.

History has shown that Couney wasn’t actually a doctor, yet his work saved the lives of thousands of babies, who went on to lead happy, healthy lives. And he did it at a time when the eugenics movement was gaining traction by promoting the idea that the weakest members of society should be allowed to die because they would be a burden and an obstacle to the “propagation of the fittest.”

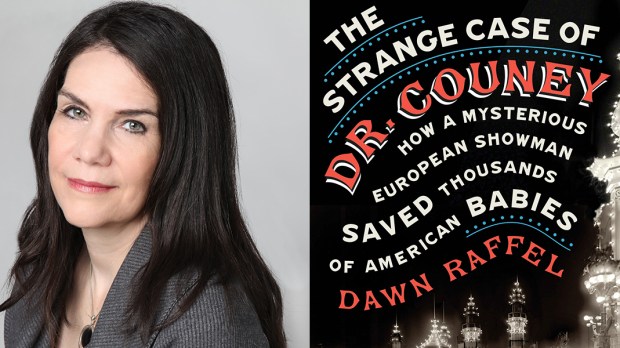

During a “Christopher Closeup” interview about her new biography “The Strange Case of Dr. Couney: How a Mysterious European Showman Saved Thousands of American Babies,” author Dawn Raffel explained that she first gained interest in this story when she saw a picture of an incubator exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair – and then again in an old photo at the Coney Island Museum in Brooklyn.

Upon investigation, Raffel discovered that alongside the sword swallowers, shooting galleries, and freak shows prevalent in sideshows of the early 20th century, there was Dr. Couney, inviting passersby into “an exhibition of live, premature infants in incubators. It was almost like a mini-hospital right out on the midway. You could pay a quarter and go look at the premature babies in incubators.”

It wasn’t the incubators alone that made the difference between life and death, but also the “skilled nurses” that Dr. Couney had caring for the babies around the clock. They knew exactly how to operate the incubators, kept the exhibit cleaner than many hospitals at the time, and were skilled in feeding the children in the only way they could really take in food: via a spoon-to-nose technique.

Though some people looked on Dr. Couney’s exhibit as “degrading…and wanted to shut him down,” said Raffel, “there were also many doctors…who sent their premature patients to him. Although they felt uneasy with the spectacle, they also understood that this was the best – and sometimes only chance for these children.”

Couney’s operation might sound exploitative to modern readers, but he was no selfish huckster, despite the fact that he embellished his credentials. Firstly, Couney never discriminated against anyone based on race or religion. He welcomed everybody.

Also, much of his work took place during the Great Depression and was a great service to the poor. Raffel explained, “People were out of work. They didn’t have health insurance. Even in the few situations where later in the 20th century there was some available healthcare in hospitals, people couldn’t afford it. Because people were paying admission to the sideshow, Dr. Couney provided the treatment free of charge. If you had [money], you would try to help him out a little bit with the expense. Some of the parents were very wealthy and they generously donated to him. But he never sent anybody a bill.”

And though Dr. Couney made a decent living with the money he generated from the exhibit, he genuinely wanted to save these children’s lives. This was a method of promoting, what he called, “propaganda for preemies.”

Why did preemies need propaganda? Because evil was being touted as a good by some powerful forces in the world.

Raffel said, “Eugenics was the very unfortunate outgrowth of the new science of genetics. People started thinking – maybe we can breed better humans, sort of the way a stock breeder would. It was very much about survival of the fittest and deciding which people should marry and who should be able to have children. And it became increasingly horrifying where you had the involuntary sterilization of certain groups of people. You also had doctors literally advocating to allow children born with severe disabilities to simply die. While eugenics did not directly target preemies in the medical literature, they were [called] ‘weaklings.’ And there was an attitude of – why are we spending resources to save these weaklings? Maybe they will never be productive citizens.”

One of the most noted eugenics propagandists of the time was Dr. Harry J. Haiselden, who did his best to convince people that babies with disabilities are better off dead. He starred in a 1917 film called “The Black Stork,” as a character based on himself.

Raffel writes, “In the silent, captioned film, the newborn is afflicted with an unidentified genetic disease. His mother is upset – to be expected – but she accepts the doctor’s wisdom after a vision of her child’s miserable future on this earth: a life of insanity and crime. When a nurse tries to hand the doctor his operating apron, he sternly refuses her. Chastened, she turns and walks away, leaving the infant to die alone on a table. The dead child eventually levitates into the arms of Jesus. One 1917 newspaper advertisement read ‘Kill Defectives, Save the Nation, and See The Black Stork.'”

Whatever Couney’s shortcomings, he at least erred on the side of life. In fact, while working on her book, Raffel met with several of the babies, now senior citizens, for whom Couney cared. They all appreciated learning more about the mysterious doctor who saved their lives.

In the long run, Dr. Couney’s name may not be easily found in medical history books, but his influence is somewhat responsible for the care premature infants receive today. Raffel said, “He had a great friend in Chicago, Dr. Julius Hess, who was a much more traditional physician who was able to take Dr. Couney’s teachings into a more clinical setting and produce clinical results, publish articles. And the friendship between these two men really had a very strong influence on the beginnings of neonatology in this country.”

Raffel also hopes that people who read her book gain respect and admiration for Dr. Couney: “I found him absolutely heroic, but he was imperfect. He fabricated his credentials. His fabrications became bolder as time went on…But if you put that on one side of the scale against saving all those lives on the other side of the scale, he was heroic…Heroes don’t have to be perfect. I think sometimes we just find ourselves in a situation where we have the possibility of making a real change for other people and we can go ahead and do that…One person can make a real difference.”

(To listen to my full interview with Dawn Raffel, click on the podcast link):