Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The Church has long had an interesting relationship with time. It was because of the influence of Christianity that we went from counting years according to the reigns of kings to numerating them as before Christ (BC) and, after His coming, the “year of Our Lord” or anno Domini (AD). The monastic practice of praying the Liturgy of the Hours throughout the day necessitated the invention of alarm clocks to wake the monks for prayers in the middle of the night. And it was by papal decree that 10 days in October once disappeared.

Scholars had long known that the solar year is not exactly 365 days, but rather, 365.25 days. Various ancient peoples had a method for accounting for this difference in their calendars. Most of Europe inherited the Julian calendar from the Romans, which would occasionally add extra days or extra months to make up for the difference. But astronomers also discovered in the early medieval period that even that was not quite right—that they had too many leap years. This became especially problematic when it came to calculating the date of Easter.

The celebration of Easter has always been tied to the Jewish feast of Passover, since it was shortly after Passover that Christ was raised from the dead. But the ancient Jews used a lunar calendar, rather than a solar one, which is why the feast of Easter “moves.” Thus, Easter (in Western Christianity) is the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox (i.e. first day of spring).

Read more:

Meet Fr. Marin Mersenne, the mind behind “prime numbers”

But as the solar calendar fell further and further into error, its synchronization with the lunar calendar fell off, too, so that by the 16th century, there was a difference of four days between what the “official lunar calendar” showed and what the actual phases of the moon were. This also meant that the date of Easter kept getting farther and farther removed from the vernal equinox, and thus farther away from the date of Passover. Easter was occurring noticeably earlier.

Thus, among the many acts of the Council of Trent was a decree that the calendar be recalculated and revised so as to combat this problem. A brief was sent to the greatest mathematicians and astronomers of the day, who worked on calculating the correct length of the year and devised a method to address it in the calendar. Through much debate, a solution was settled upon. First, the calendar would not simply have a leap year every four years, but only 97 out of every 400 years, so that years divisible by 100 would be leap years only if they were divisible by 400 as well. Second, the lunar calendar would also be occasionally updated to correct for mistakes. And third, most radically, 10 days would be eliminated to correct for the drift that had taken place, so that the vernal equinox would take place on March 21 again instead of March 11.

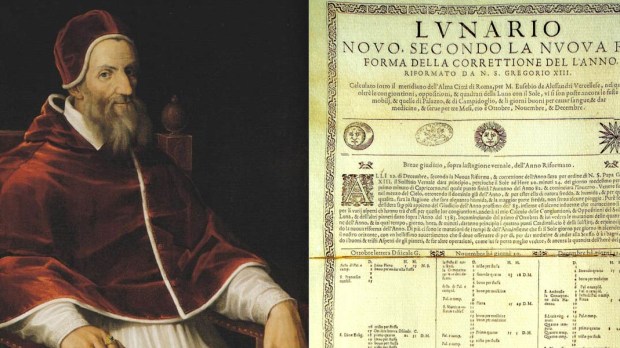

Since the calendar reform was ordered by an ecumenical council, it was the pope who would put it into effect. So, by the papal bull Inter gravissimas, Pope Gregory XIII instituted the new calendar and declared that the day after October 4, 1582, would be October 15, 1582. October 5 through October 14 never happened.

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar was not immediate and worldwide, and actually followed denominational lines. Catholic countries like Spain, Portugal, France, and Poland adopted it that year, while Protestant and Orthodox countries took decades and even centuries to make the switch. Great Britain did not move to the Gregorian calendar until 1752, and Greece did not until 1923!

Read more:

The scientist nuns: In pursuit of faith and reason

One curious casualty of this historical oddity was St. Teresa of Avila. The holy Carmelite passed away some time in the evening of October 4, 1582—however, the exact time is not known. Thus, a difference of a few minutes would have determined whether St. Teresa died on October 4 or October 15.

We often speak of the pope having more temporal power in past times—but this is something altogether different!

Read more:

Why an indulgence of so many days never was about getting time off Purgatory