Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Picture this: A child looks at today’s headlines, looks at social media for an hour, listens for an hour to how Catholics talk to and about each other and asks, “When did God leave? And where did He go?” Could we blame such a child for asking those questions? Seeing daily life as it most commonly presents itself in our manic world, how could an innocent child not wonder whether God, in exasperation, has left fallen humanity to its fate?

Has God in fact abandoned creation, or is he as ever-present as he has always been, and we have just become numb, blind and deaf to his presence? I put those questions to renowned Catholic philosopher Peter Kreeft of Boston College during an interview last week.

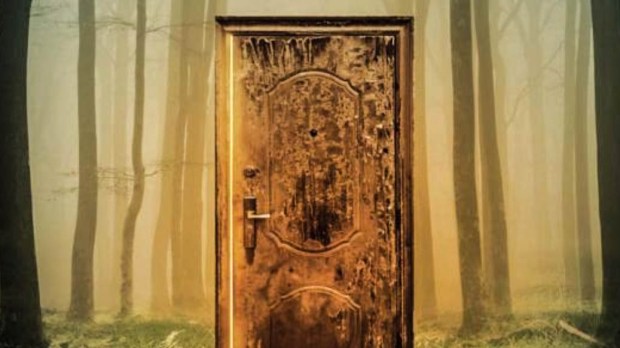

We began with a discussion of his latest book, Doors in the Walls of the World: Signs of Transcendence in the Human Story. (It is a most charming and winsome book and I recommend it highly.) Kreeft insists that God has not changed—and neither have we. He says that we have been trying to hide from God (unsuccessfully, of course) since the Garden of Eden. God, in response, has pursued us relentlessly, throughout salvation history. And God has embedded throughout all of creation and all of human life hints, clues and invitations—which Kreeft refers to as “doors in the walls of the world.”

Kreeft writes, “A wall is a limit. A door in a wall is a way of overcoming that limit, a way out of the place confined by the walls. The walls here symbolize the physical universe. The doors symbolize escapes from that limit, ‘moreness,’ transcendences. The point of this book is that there are many doors through the walls of the world, many Jacob’s Ladders through the sky.”

In other words, the walls appear as the outermost limits of what is contained in the “merely ordinary,” the mundane. Many in our culture would have us believe that this physical world before our senses is all that there is—and the physical world has no place or need for the divine. Kreeft is saying that with just a bit of alertness, we can see the doors that point to something else, something beyond the apparently sufficient and comprehensive physical world (the so-called “real world” my students liked to speak of). Once we see those doors, says Kreeft, we may begin to wonder what is on the other side. That wonder can begin a re-enchantment of human life, leading to philosophy (understood as the love of wisdom, not just academic pretense) theology and mysticism. That is, the doors point to possibilities and the fullness of life that life within the walls of the world can never offer.

Read more:

How to pray with icons: A brief guide

While life within the walls promises pleasure, and perhaps happiness, Kreeft says, the doors in the walls of the world point to joy:

Pleasure is to the heart what sense experience is to the head. Happiness is to the heart what knowledge is to the head. Joy is to the heart what wisdom and understanding are to the head. It is at the bottom … Happiness is partly controllable, as pleasure is; joy is always a surprise, a gift. Happiness makes us smile; joy makes us weep. Happiness is obvious; joy is mysterious. For one moment of joy, we would gladly exchange months of happiness. It breaks our heart, and we bleed. It squeezes our heart, and tears come out. It hollows our heart and enlarges it.

Kreeft, like C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton before him, like the Psalmist ages before them, speaks of a longing, a desire for joy that stubbornly points towards the doors in the walls of the world. The Latin roots of desire, Kreeft notes, is de sidere, which means, “from the stars.” The longing, the desire for joy, for the transcendent, can only come “from the stars,” that is, only from what is far beyond the ordinary scope of life within the walls of the world.

Much of the 20th century can be read as a chronicle of man’s attempts at stifling the desire for joy. That bloody century (and this mad one) instead promised constant pleasures, or the state-defined, state-provided, state-enforced “happiness” of political utopias. (Such utopias end in the slaughters of Pol Pot’s Cambodia and Mao’s Cultural Revolution.)

Let’s answer the child we first spoke of: “My love, God never left. We can’t see him because we closed our eyes, minds and hearts to him. If we open up, look and listen, we can find our way home to him. Let’s go!”

When I write next, I will consider how we all might support those who are in the front lines, fighting against the darkness in this present time of crisis. Until then, let’s keep each other in prayer.

Read more:

Just 2 min a day with the Gospels, and your life will change, says Francis