Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, the Civil War reached the Pennsylvanian town of Gettysburg, in what would be remembered as the largest and bloodiest battle of the war. But while there have been dozens of documentaries and motion pictures depicting the hard-fought battle, the efforts of the citizens of Gettysburg to care for the wounded and dying are often overlooked. These charitable souls were fighting a battle of their own — one that would last far longer than two weeks after hostilities ceased — as they tackled the seemingly insurmountable task of caring for the endless stream of wounded and dying soldiers who sought respite from the nightmarish ordeal of war.

The wounded came in such great numbers that every large building in the town was commandeered as a hospital. One of the first buildings to open its doors was St. Francis Xavier Roman Catholic church, which was already in use as a hospital by noon of the first day, just 5 hours after the fighting began. It was primarily used as a place for amputation, a grisly task that was the only option to prevent gangrene, blood-poisoning, and death when dealing with shattered limbs.

St. Francis’ was furnished with 64 pews, but every other one was removed so that attending doctors and nurses could better reach patients who, one account recalls, were lying in any open space on the church floor:

“So crowded was the Catholic church that the wounded lay in and under the seats and in the aisles. Later, when more arrived at the doors, they were placed in the sanctuary and in the gallery … the men were laid so close together that the attendants could hardly move about.”

The records of J. Howard Wert, a citizen of Gettysburg who witnessed the horrors at St. Francis, describe the church on that day:

“There were gruesome sights all around. The sacred edifice was filled with suffering humanity. Groans and shrieks and cries of agony rent the air. In the little yard of the church stood the amputating tables and the surgeons at them, bedabbled with blood, were ceaseless in their work, whilst legs and arms, deftly cut off, were being thrown upon an increasing pile.”

In the fledgling church, which was only about 11 years old at the time, physicians were indiscriminate in their work, caring for Union and Confederate soldiers alike. Boards were placed across what pews remained in order to give the wounded a place to lie — the pews were too narrow to act as cots. The wooden floor was slippery with blood; with little time, and few workers to clean up between patients, piles of amputated limbs began to form.

The entire community pitched in during this time of hardship. Households were drafted to cook much-needed meals for the injured, and the young women of Gettysburg were drafted as nurses. One woman of note, Elizabeth “Sallie” Salome Myers, kept a journal which gives us great insight into the care these young women provided for men on their deathbeds:

“I knelt beside the first man near the door and asked what I could do. ‘Nothing,’ he replied, ‘I am going to die.’ I went outside the church and cried. I returned and spoke to the man — he was wounded in the lungs and spine, and there was not the slightest hope for him. The man was Sgt. Alexander Stewart of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers. I read a chapter of the Bible to him; it was the last chapter his father had read before he left home.”

Along with her duties as a makeshift nurse — bringing food to patients, applying fresh bandages, helping doctors as directed — Sallie walked from man to man with a pen and paper, transcribing letters to the men’s families and reading letters that came for them. She also did what she could to comfort family and friends who came for their loved ones. Sallie performed her duties admirably and with humility. She wrote:

“I would not care to live that summer again, yet I would not willingly erase that chapter from my life’s experience; and I shall always be thankful that I was permitted to minister to the wants and soothe the last hours of some of the brave men who lay suffering and dying for the dear old flag.”

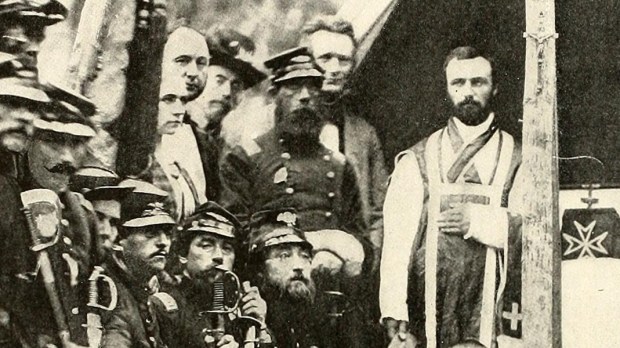

Sallie and the other young women of Gettysburg would not work alone for long, however, as just to the south, over the Maryland border, was the convent of the Sisters of Charity. When the battle had ended, a priest and the Mother Superior led 14 nuns to brave the war-torn roads to Gettysburg, an account of which can be heard here. They began their charitable efforts immediately, caring for the infirm as the only trained nurses in the area.

These nuns worked tirelessly to tend to the hordes of casualties brought to town. In the latter days of their work they ran out of bandages, at which point they began tearing what pieces they could spare from their habits and used them to patch wounds. One member of the order, Sister Camilla O’Keefe, wrote an account of St. Francis Church:

“The Catholic church in Gettysburg was filled with sick and wounded … The soldiers lay on the pew seats, under them and in every aisle. They were also in the sanctuary and the gallery, so close together that there was scarcely room to move about. Many of them lay in their own blood … but no word of complaint escaped from their lips.”

The nurses not only provided comfort to the mangled bodies of the men, they also tended to their souls. Many of the men died with these holy women comforting them with the assurance of God’s infinite love and mercy; some even requested baptism. It is said that the doctors especially appreciated the presence of the nuns, as their order had accumulated hundreds of years of nursing experience. Indeed, in the 1860s nuns were the only trained nurses in the nation.

Today, in St. Francis Church, there is a stained glass window commemorating the service of these nuns, dubbed the “Angels of the Battlefield.” The Catholic community there still thrives. More can be read about their efforts during the Civil War on their website.