To an English speaker, our Catholic faith is filled with foreign words. There’s a lot of Latin—sanctus, miserere, etc. There’s a gaggle of Greek words—Eucharist, kyrie, apostle, etc. When you begin to study theology, you start to pick up more German and French terms, like gemeinschaft and ressourcement, as so much theology has been written in those languages.

The English language is more of a latecomer in the game. It hasn’t given a whole lot to theological discourse, but it has contributed one especially important word: atonement.

I was surprised to learn (and you might be, too) that the English word “atonement” was actually invented as a sort of pun! Its origin is as a smashing together of “at one,” with the –ment indicating an action accomplishing it. So, “atonement” is “at one-ment, bringing two things together.”

(There’s also a funny story with the origin of the word “reconciliation.” At one time scholars thought that the root of the word was the Latin for eyelash, cilia, so that to be reconciled with someone is to be “eyelash to eyelash again.” A beautifully evocative image—but it turns out that that wasn’t the origin of the word after all.)

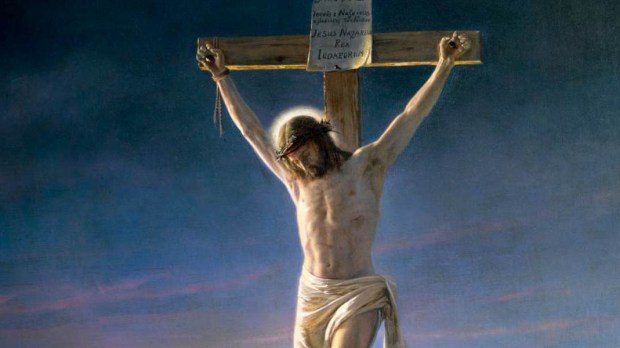

We use this word atonement in theology to describe the effect of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. His pure offering of Himself, made out of infinite love, satisfies the debt owed for our sins and allows us to be reconciled to God. We see it, and similar words, used throughout Scripture, Tradition, and the teachings of the Church.

The English word atonement has been used to translate several related words in Greek and Hebrew in the Bible. The Hebrew word kippur appears several times in the Law of Moses to describe the sin offerings made by the people of Israel to God. The conclusion of the High Holy Days of Judaism is Yom Kippur, “The Day of Atonement.”

For example, Leviticus 25:9 says, “You shall then sound a ram’s horn abroad on the tenth day of the seventh month; on the day of atonement you shall sound a horn all through your land.”

In the New Testament, the word katallage, meaning “reconciliation” or “restoration,” has likewise been translated as “atonement.” For example, the King James Bible translated Romans 5:11 as “And not only so, but we also joy in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom we have now received the atonement.”

The Eastern Church Fathers often focused on the atoning effect of the Incarnation itself. By God taking to Himself a human nature in the person of the Word, humanity was united with divinity, thus leading the way to our salvation. As St. Gregory of Nazianzus wrote, “That which was not assumed is not healed; but that which is united to God is saved.” In Jesus, God and humanity become one—so in that sense, the Incarnation itself is an “at-one-ment.”

In a similar vein in the West, in his famous work Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man), St. Anselm of Canterbury put it this way: Humanity owed God an infinite debt, a debt they could never repay. Because God is infinite, the offense of our sins against Him is immeasurable. And because we are finite, limited human beings, we could never make an act to measure up to it. What was needed was someone who was truly human, who could make a truly human action on behalf of humanity who owed the debt, but who was also God, who could do an act of infinite value. Thus, God became man in the God-man, Jesus Christ.

Read more:

What is “clericalism?”

Christ could pay the debt on behalf of humanity, but, being sinless, He Himself did not owe any part of the debt. Thus his loving action was all the more valuable, as St. Thomas Aquinas wrote: “But by suffering out of love and obedience, Christ gave more to God than was required to compensate for the offense of the whole human race.” (ST III, q. 48, a. 2, c.)

Only the sacrifice of Christ, only the loving action of God Himself, could make this atonement possible. As the Catechism says, “It is love ‘to the end’ that confers on Christ’s sacrifice its value as redemption and reparation, as atonement and satisfaction. He knew and loved us all when he offered his life.” (CCC 616)

This all might sound a bit abstract. It’s important to keep in mind, to paraphrase C.S. Lewis, that Christ did not die for humanity, but for each human being. Jesus came not to reconcile some abstract mass to God the Father; he came so that you, and I, and every person that has ever lived might be “at one” with God, redeemed and joined in love with the Trinity for over.

No matter our sins, Jesus calls us to be at one with God. The Church is given to us as the instrument of this reconciliation, bringing the grace of the sacraments, the life of God Himself, to make as “at one” with the Body of Christ.

Read more:

A powerful collection of prayers to the Holy Wounds of Christ