When the Germans invaded Austria, he was number one on Hitler’s list of people he wanted captured and killed. All he’d done was write. He hadn’t tried to assassinate Hitler, as the Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer did a few years later. That ticked off Hitler, for understandable reasons.

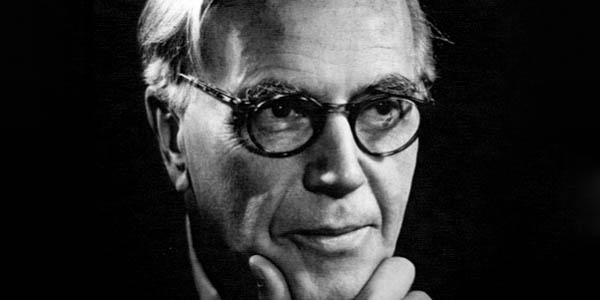

The Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand had simply written the most penetrating analysis of the horror of Nazism. He’d had to flee his native Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. He set up next door in Austria and kept at it. From 1934 to 1938 he edited a magazine called Die Christliche Ständestaat or “the Christian corporative state.” He wrote a stream of anti-Nazi editorials.

He didn’t vent. He explained. That angered Hitler, because even that wicked man knew the power of truth, and hated it. Hildebrand, he declared, must die. Hildebrand kept writing even with a price on his head. He and his wife barely got out of Austria when the German army swept in.

Here are five of Hildebrand’s insights into patriotism, taken from his articles in the magazine he edited, called Die Christliche Ständestaat (“The Christian Corporative State”). You can find these in My Battle Against Hitler. (I did the copy-editing of this book, I should say.)

I should warn you that Hildebrand didn’t write like C. S. Lewis. He was a philosopher, and a German philosopher at that. But he tells us a lot we need to know, because he’d seen evil up close. I have combined some quotes and smoothed out his writing here and there.

What real patriotism is

Hildebrand calls real patriotism “morally positive” and even “obligatory.” In fact, it’s a “divinely ordained, well-ordered love” for the nation in which our birth has placed us. Real patriotism, he writes,

“affirms the value that resides in the national community as such, considered as a spiritual space with an individually distinctive character, a space into which the individual has been placed. It includes a special sense of belonging to the nation of which one is a member, love for the ‘divine idea’ this particular nation represents, a special familiarity and solidarity with it, gratitude for everything that one receives from it, a special understanding one possesses for it, and finally the task that is given through belonging to it.”

What real patriotism is not

Hildebrand fought nationalism. That was one, although just one, of the fundamental problems with Nazism. Let’s call it “fake patriotism.” The mildest form identified the nation with its government. That would be what we call the “my country right or wrong” idea. Hildebrand describes the worst form (the Nazi form) as

“committing idolatry toward a nation, that is, making the nation the highest criterion for the whole of life and making it the ultimate and highest good. It regards the unity of the nation as the ultimate and most vital bond of community.”

How do you spot this? You see it, he writes,

“wherever the nation is ranked above communities of even higher value, such as larger communities of people or mankind as a whole. This perversion reaches its culmination when the nation is ranked above the highest community of them all, namely the supernatural community of the Church understood as the mystical body of Christ. Nationalism also manifests itself when the individual is regarded a mere means for the nation to exploit.”

You also see it in the way nationalists — fake patriots — think about their nation. He called their attitude “collective egoism.” The nationalist doesn’t say “I’m more important than anyone else.” He says “We’re more important than anyone else.” Hildebrand writes:

“Nationalists never see the true values of their nation. All they see is its power, its glory, its political influence. It is not love at all: it is self-assertion, the will to power, the drive for prestige, and self-glorification. He confuses the true value of his own nation with an imperialistic need to command the attention of other nations.”

Real patriotism elevates the individual

Nationalism, fake patriotism, tears down the individual. Hildebrand writes passionately against this. Real patriotism recognizes the greatness of each man and woman.

“Anyone who does not see in other persons first and foremost a soul created by God and for God has already succumbed to this heresy, and the same is true of the one who sees a German, Frenchman, or Italian first, rather than a human being with whom he shares a profound connection through their great shared destiny, which encompasses birth, death, personal creatureliness, and the ordination toward eternity.”

Real patriotism respects other countries

Because Hildebrand saw that each nation had a distinctive character, he saw that every country has value. Real patriotism, real love of one’s own country, he argues,

“entails that one acknowledges every foreign nation in its particular character as something justified and valuable. Certainly, a person’s love for his own nation will be greater, more intense, and of a different kind. But every person who refuses to grant other nations the right to develop freely, who holds that he can ignore their rights and justified wishes, and who imagine s that he may trample them underfoot if it should help his own country, thereby contradicts the very foundation that validates his love for his own country. He is, to put it bluntly, incapable of truly loving his own country.”

Real patriotism does not separate people by race or any other marker

Hildebrand was writing against a political movement and ideology that explicitly dehumanized most of humanity. The Nazis hated Jews, of course, but they hated lots of other groups as well. Their racism was mixed up with their nationalism. Hildebrand would have none of it.

“Every man, whatever his race, is created by God and after His image. Every man has an immortal soul destined for eternal communion with God. Race, according to Catholic doctrine, is a quite secondary and accidental biological factor, having no effect upon the possibility of man’s attaining his eternal end, since the values he is called upon to exemplify are by no means determined by race. Men as such are all equal before God: all are fallen in Adam, all are redeemed in Christ.”

Hildebrand made his way to the United States in 1940, and taught philosophy at Fordham until he retired in 1960. He died in 1977. He wrote a lot of books on an astonishing range of subjects. His work, especially his writing on marriage, influenced both the Second Vatican Council and Pope St. John Paul II. You can find his own short story of his life here http://www.catholicauthors.com/vonhildebrand.html . You can learn more about him and his works at the Hildebrand Project http://www.hildebrandproject.org/ , which is dedicated to advancing his teaching.