Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Westminster Abbey receives more attention than any church in the UK. Last week the world’s eyes were turned to the interment of Stephen Hawking’s ashes, and although the astrophysicist was by no means a religious man, the Abbey has come to stand for many different strands of English life, including celebrity weddings and funerals. There are more than 3,000 bodies buried or commemorated within its walls and floors. Most have been significant in the history of England.

Launch the slideshow to see the treasures of the England’s Catholic past:

It is also a fully functioning church. This is an aspect that is sometimes forgotten by the countless visitors who queue outside. Now the church has an impressive new museum that is a vast improvement on the earlier version, with an astonishing space high up in the building. The views it gives of the Abbey’s interior are unmatched, providing a vantage point that will be familiar to the millions who watched the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton. This was where the high-angle television camera was placed.

The new galleries give visitors a chance to see more of the Abbey’s Catholic past, without creating a conflict with the Protestant decorative touches that have been in place since Henry VIII dissolved the old monastery and turned it into a Church of England cathedral. His motive for declaring himself head of the Anglican Church in 1534 was not just to legitimize his marriage to Anne Boleyn. Monasteries were rich institutions and Henry was a big spender. Less well known is the fanaticism with which the king regarded the Second Commandment. Bans were put on “Wandering to pilgrimages, offerings of money, candles or tapers to feigned relics or images, or kissing or licking the same, saying over a number of beads not understood or minded on, or such like superstition …”

Apart from some relief when Henry’s Catholic daughter Mary ruled the country, it has remained a largely crucifix-free zone. There are still aren’t many on display, even in the ecumenical surroundings of the new Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries, opened appropriately last week by Queen Elizabeth. There would have been more if they hadn’t been destroyed in the iconoclastic relish of the Reformation and then practically finished off a century later by Puritan zealots. In 1643 Westminster Abbey was purged of what hadn’t been destroyed earlier. With so many royal associations, much had been preserved during the Reformation. With Puritan supremacy, it was out with “all scandalous pictures and the statues and images in the tombs and monuments.”

By the 19th century the Abbey was regaining some of its old Catholic presence. A high altar was built to replace the one that had become an oak communion table. Placed at the bottom of the steps, it was all about getting closer to the congregation. In more recent times, another bit of reclaimed ground was the most famous event to happen there in the past 21 years. The funeral service of Princess Diana took place at the Abbey, after which she was buried at her family home in Northamptonshire. In her hands was a rosary — a gift from St. (Mother) Teresa — the very “beads not understood” that so distressed Henry VIII and his even more radical son Edward VI.

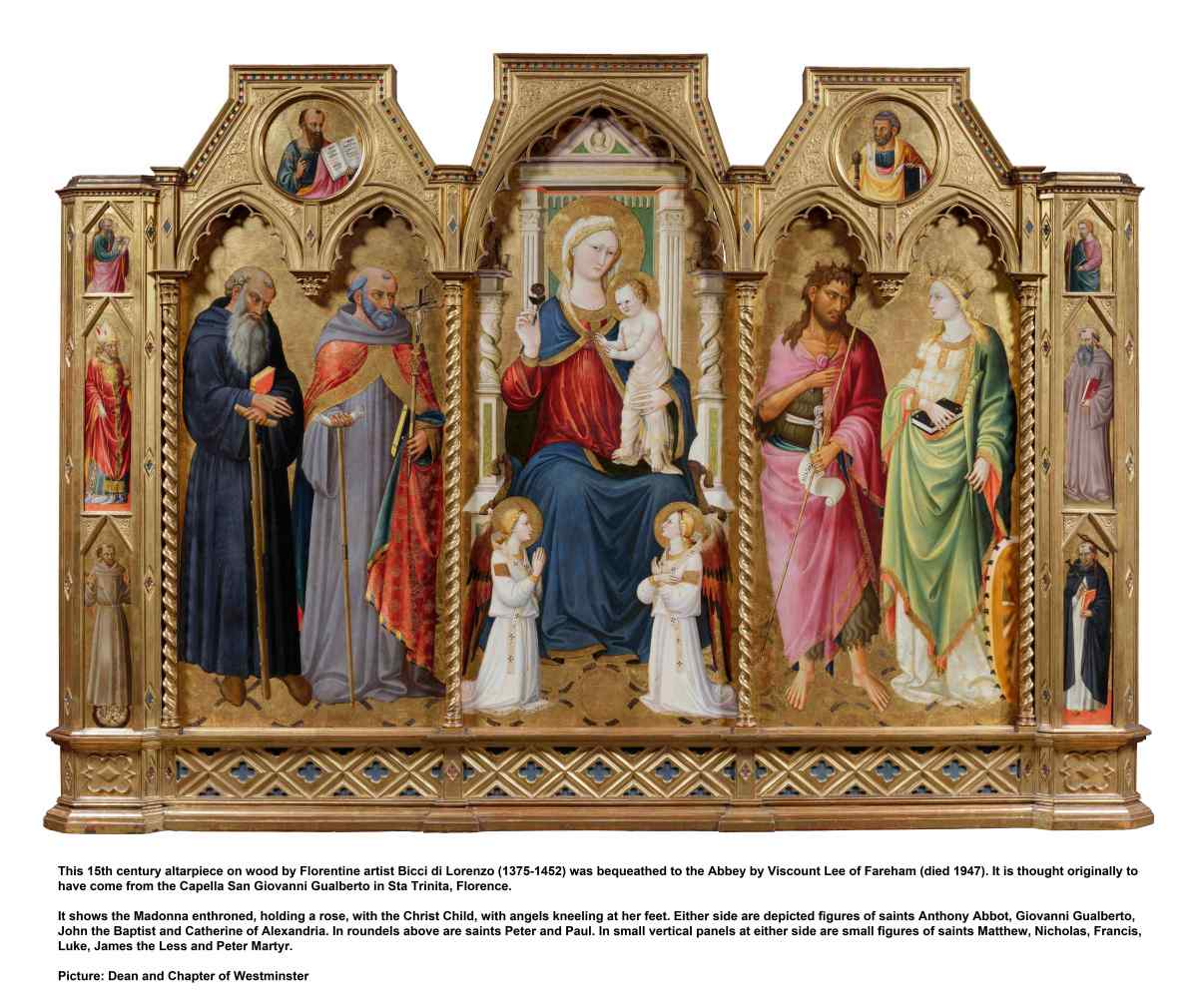

With the opening of the new galleries there is plentiful pre-Reformation, Catholic material on view again. The most impressive is the Westminster Retable. It is the oldest altarpiece in England, created in the 13th century, and is one of the few pre-Reformation painted religious works to have survived at all. Its survival is especially surprising as the key figure is the patron saint of the Abbey, St. Peter. His association with Rome would have been noticed by reformers on the lookout for signs of “popery.” Until the 19th century it had been used as a storage receptacle but is now restored to a condition appropriate to the work of art that it is.

At the other end of the aesthetic spectrum, and almost as rare, is a medieval monk’s boot. It’s a poignant reminder that this was once an important monastic community. There were few other centers of learning in England at that time, and a monk’s footwear is not the sort of relic that was widely preserved. Of a more spiritually Catholic nature, there are also missals and prayer books that would have Henry VIII (buried in Windsor) and Edward VI (buried in Westminster Abbey) turning in their graves.

Surely the most Catholic feature of the new galleries is not the exhibits; it is the view into the nave. Those endlessly climbing columns inspire as much awe from this unusual perspective as they must have done to the faithful in medieval times, stuck as firmly as they were to the ground and never seeing a building taller than the Abbey. It is this sense of the visually sublime, rather than the drone of the pulpit, that brings the experience back to its Catholic roots.