The use of DNA is giving us a new picture of what happened after migrants first came to the American continent from Asia. Though the story is far from completely known, a new study has begun to shed light on history that has been shrouded in darkness for tens of thousands of years. And it is calling into question previous assumptions about the migration patterns of the first Americans.

A study published May 31 in the journal Science says that early inhabitants split into two populations over 13,000 years ago and remained separated for thousands of years but eventually met again and began commingling, according to the New York Times:

The findings emerged from a study of 91 ancient genomes of people who lived as long as 4,800 years ago in what are now Alaska, California and Ontario. They represent a major addition to the catalog of ancient DNA in the Western Hemisphere.

“This study is important because it begins to move us away from overly simplistic models of how people first spread throughout the Americas,” said Deborah A. Bolnick, a geneticist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Traditional archaeology has been able to provide good estimates for how many thousands of years ago various sites in the Americas were settled, but it hasn’t been able to say how the peoples who settled in those sites may have been related to one another.

Early studies on small fragments of genes suggested that all Native Americans south of the Arctic descended from the same group of migrants, the Times explained. But Native Americans reluctant to cooperate with scientists have slowed down the progress of research in recent years. Not only were living Native Americans reluctant to give up DNA samples, museums also were hesitant to allow geneticists to take samples from skeletons, which often were exhumed without consent. Native American communities reclaimed many of these remains and often turned down research requests, the Times said.

But thanks to outreach on the part of scientists like Ripan Malhi, a geneticist at the University of Illinois, and Christiana Scheib, of the University of Tartu in Estonia, things are changing. Both Malhi and Scheib are co-authors of the new study.

Comparing DNA samples from 91 sets of remains with publicly available genetic information from both living and historical Native Americans, as well as DNA samples from Asia, the researchers started to see certain patterns: migrants moving across the Bering Strait, through what is now Alaska and Canada and down the western coast.

Soon afterward, that original population split into two groups, which Dr. Scheib and her colleagues call ANC-A and ANC-B.

The two groups clearly settled in different parts of North America, but there was also evidence of later mingling in what is now California, Mexico and South America. The researchers speculated that:

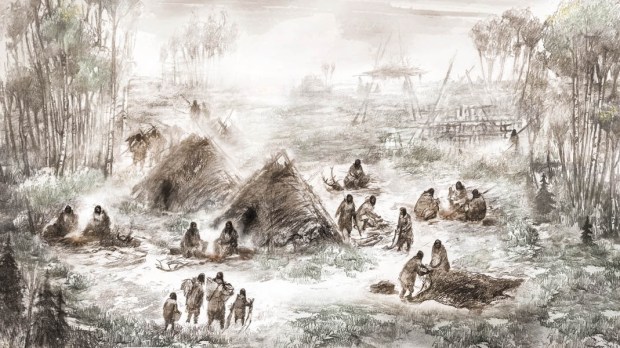

ANC-A people moved down the western coast of the Americas, establishing fishing communities along the way. Thousands of years later, a lineage of people descending from the ANC-B group also expanded southward, making contact with those communities.

To shed further light on the findings of science, the researchers said, they hope to learn something from the oral traditions of Native Americans. The Times explained:

One way to explore these hypotheses is to find more ancient DNA from other parts of the Americas. But first Dr. Malhi said that he and his colleagues also want to talk with living Native Americans about their histories. Their stories may preserve information about contacts between distantly related peoples in the far past.

“I think that most people have this idea that a single, simple wave [of people entered the Americas from Beringia],” Jennifer Raff, the University of Kansas, told the Atlantic. “But I suspect it was more like driblets of small groups moving down—and up—the coast, meeting up with each other to trade and marry. I expect that the more ancient genomes we get from North America, the more complex it’s going to become. It’s a very exciting time to be working in this field.”