I’m trying to “offer up” my suffering more often, even though I don’t understand how it helps. Generally, I need to actually practice these things before they start making sense, so I’ve been trying to shoot off a quick prayer when I get a headache, or my kids go on a napping strike, or when my family needs me, and I’m exhausted.

For those unfamiliar, this practice of “offering up” our pain, frustrations, or plain inconveniences, has a long and rich history in the Church, profoundly rooted in the whole mystery of our redemption. More recently, Pope Benedict XVI called for a resurgence in this practice:

There used to be a form of devotion—perhaps less practiced today but quite widespread not long ago—that included the idea of “offering up” the minor daily hardships that continually strike at us like irritating “jabs,” thereby giving them a meaning. … What does it mean to offer something up? Those who did so were convinced that they could insert these little annoyances into Christ’s great “com-passion” so that they somehow became part of the treasury of compassion so greatly needed by the human race. In this way, even the small inconveniences of daily life could acquire meaning and contribute to the economy of good and of human love. (Spe Salvi, 40)

It’s a mystery how all of this could work, as even the professor-pope suggested. But all these little “jabs,” as Benedict called them, are, if this is the right word, useful, somehow.

And I don’t have to know more than that. On a good day, that faith means I can offer up these kinds of things pretty happily.

It’s better than I thought, though.

Broadening the box

I was reading Heather King’sShirt of Flame, and I realized that I’ve had an absurdly impoverished idea of what kinds of things can be “of use” to God. I can’t even tell you how much it has cheered me up.

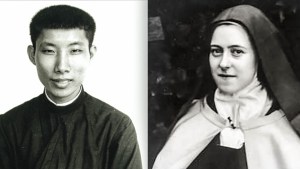

King is recounting St. Therese of LIsieux’s childhood, when 11-year-old Therese was struck with what we might now call a nervous breakdown: “Hyperventilation, hallucinations, and agitation so extreme,” King writes, “that Therese took to hurling herself with frighteningly violent force against the walls of her bedroom.”

When the sickness lifts, though, Therese is afflicted with a new, worse kind of suffering. She writes, in Story of a Soul, “For a long time after I got well I thought that I had become sick on purpose, and that was a true martyrdom for my soul.”

I know people who live in a fog of chronic illness, and I’ve seen them offering up their pain, day after day, to Our Lord. The huge things, and the little ones, I’ve always understood, can be united with His cross. But St. Therese sees the period after her illness as an even worse suffering than the fits themselves. The fear that maybe she just wanted the attention, the guilt, the embarrassment of it all? I’d never have considered that these were martyrdoms, too, that they could “count,” too.

What if all of it counts? Not just the physical pain we go through, and not just the simple, definable pain — disappointment, frustration, fear — either. I’m talking about the messy stuff. I started looking in my own soul for all those overlooked opportunities for a martyrdom that could unite me to Christ, and the list grew and grew:

There’s a whole pile of things that are in my power to change, but still hurt. Couldn’t I offer up the stress of a sink full of dishes, even though that stress is entirely my own fault? What about offering up the pain that comes from my guilt and my fear, when I can hear myself acting out in anger, and don’t know how to get it to stop? My sins cause me so much suffering. Can I offer up the pain that comes directly from my own weakness?

Read more:

The priest ended my confession with this prayer and wow! It’s so beautiful!

There are things I can’t change, too. The feeling of helplessness that comes from needing an antidepressant, or a break, or even a nap. That could count, right? The realization that my willpower is nowhere near able to get me through the day … the pain of seeing myself, and disliking who I see, the fear of being misunderstood and rejected. My psyche seems to be a treasure trove of pain and weakness and sorrow. These can be little martyrdoms, too, if we let them.

We know, and we teach our children, that offering up some pain to God means more than we could possibly comprehend — so let’s offer even more of it up, let’s offer all of it up, the noble, and the ugly, that which we can control, and that which we can’t.

If Christ were not truly human, truly like us “in all things but sin,” we could never join our sufferings to his, for the sake of the world. But Christ is human now — fully God, but fully man. His body was tortured to death, but he also lived with a human mind, and we all know that the human mind can cause us more pain than the body ever could.

Since I started acknowledging how broad the spectrum of human pain can be, and trying to offer all of it to God, not just the neat, predictable parts — well, it might be years before I understand the fruit of all this. But for right now, what I know is that it’s brought Christ’s face, his human face, deep into every crevice of my life, where he is very welcome, and desperately needed. It’s a good start.

Read more:

“God has tattooed my name on his hand!” Pope Francis is blown away by God’s mercy

Read more:

Why does fasting have anything to do with a far-away war?

Read more:

Miracle in Vietnam: When St. Therese appeared to a man and taught him to be an “apostle of love”