One challenged the idea that the earth was at the center of the universe. Another developed the theory of the Big Bang. One provided the foundation of modern genetics. The other was one of the greatest seismologists of his day. They were all great scientists as well as faithful Catholics. All but one were priests. One held dual doctorates in theology and physics. Here are five scientists who transformed their disciplines, revolutionized our understanding of the world, and demonstrated the harmony of faith and science in their works.

Nicolaus Copernicus

Born in 1473 in present-day Thorn, Poland, Nicolaus Copernicus was headed for a career in medicine and law when he discovered his passion for astronomy. He would go on to become one of the great figures of the Scientific Revolution, remembered for challenging the traditional geocentric model of the universe in which the earth was at the center. Instead, Copernicus proposed a sun-centered, or heliocentric, model. His ideas were presented in his book, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, published in 1543, the year that he died.

Copernicus was a true Renaissance man. Despite his interest in astronomy, he eventually obtained doctorates in both medicine and law. He earned a living as a Church canon, managing the properties and finances. He also translated the works of the 7th-century Byzantine historian Theophylact, wrote a treatise on money, and practiced medicine on the side.

He came from a devout Catholic family. Two brothers become clerics, one sister entered the Cistercian order, and the family was in the Third Order of St. Dominic, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia. While other scientists of his era would run afoul of the Church, Copernicus was on good terms with ecclesiastical authorities. He addressed the preface of On the Revolutions to Pope Paul III. He wrote, “I am aware that a philosopher’s ideas are not subject to the judgment of ordinary persons, because it is his endeavor to seek the truth in all things, to the extent permitted to human reason by God. Yet I hold that completely erroneous views should be shunned.”

Even as he challenged many of the reigning orthodoxies of his day, Copernicus remained respectful for the authority of the Church. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, “What is most significant in the character of Copernicus is this, that while he did not shrink from demolishing a scientific system consecrated by a thousand years’ universal acceptance, he set his face against the reformers of religion.”

His book was briefly added to the Church’s Index of Prohibited Books in 1616 amid the Galileo controversy, but it was removed within a few years after some minor corrections had been made to just 10 sentences, describing heliocentrism as a hypothesis rather than fact, according to Catholic Answers. In 2008, his remains were identified and, two years later, they were blessed with holy water and reburied, according to Space.com.

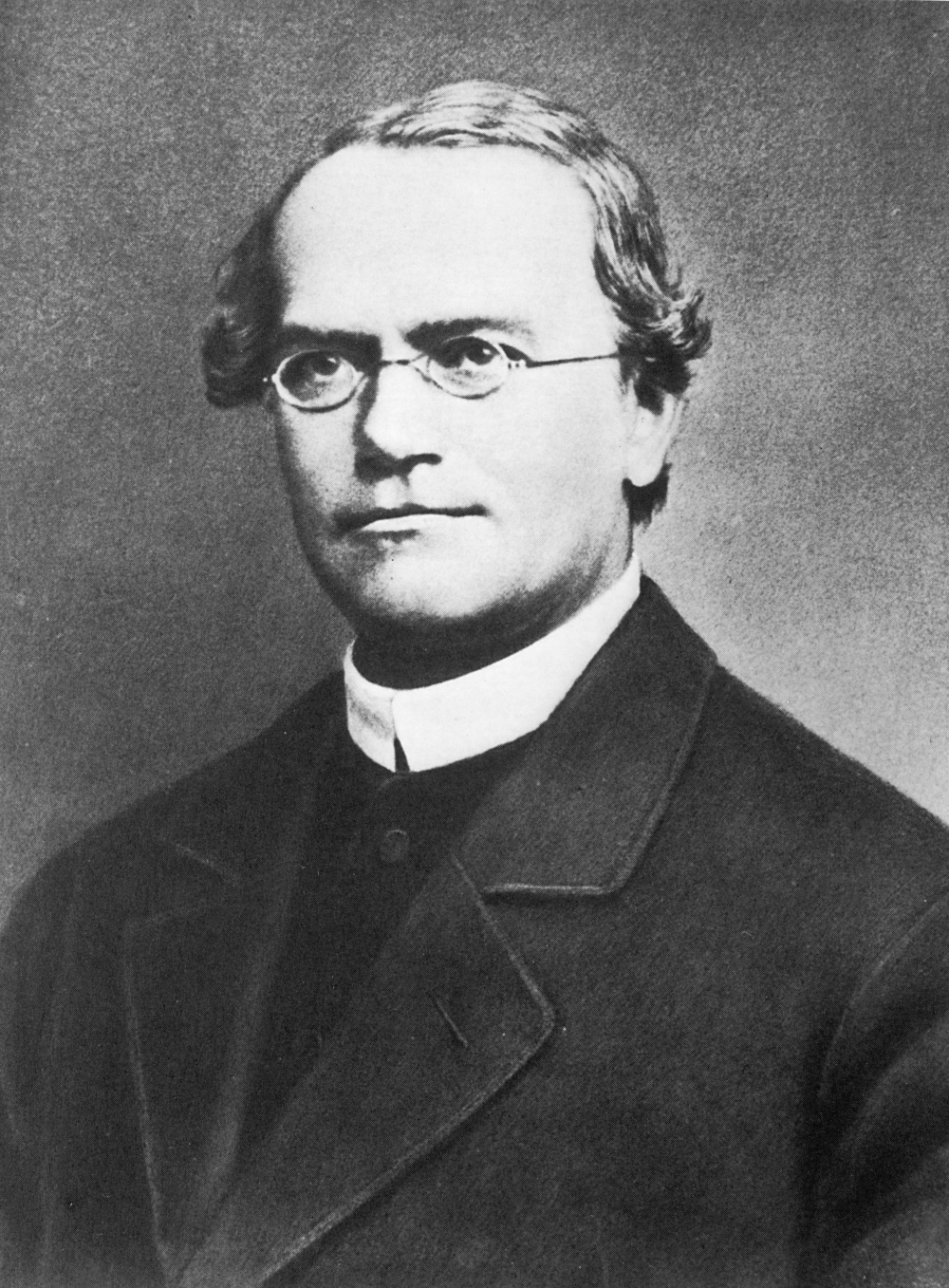

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel was a 19th-century Austrian monk remembered for his experiments with pea plants that led to the discovery of hereditary patterns of traits. By cross-fertilizing plants of different traits—such as height or color—Mendel was able to identify dominant and recessive trains and show that traits were transmitted independently of the others, according to biography.com.

These observations later came to be known as Mendel’s laws, and his accompanying theory was dubbed Mendelism. Although he did not actually discover genes, he hypothesized the existence of gene-like units. His work became the basis for all subsequent studies of genetics. (The word gene was not coined until 1905, decades after Mendel’s death.)

Mendel was born in 1822 to a poor peasant farmer in Austria. After studying physics and mathematics at the University of Olmütz, he entered the Augustinian order at the St. Thomas Monastery in Brno, in the present-day Czech Republic. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1847. He became a substitute teacher but, after failing a certification exam, he went to the University of Vienna, where he studied under physicist Christian Doppler, for whom the Doppler effect is named.

After Vienna, Mendel returned to teaching, becoming the abbot at the high school where he worked. It is also during this period that he started his experiments with the pea plants in the monastery’s garden. He also experimented with bees, but his notes on his results have been lost, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia. He would later present his findings on hereditary traits in a series of lectures at the Natural Science Society in Brno. He died in 1884 and his theories faded into obscurity until their later revival at the start of the twentieth century.

Fr. Giuseppe Mercalli

Giuseppe Mercalli was a 19th-century Italian priest and seminary professor who studied volcanoes. He spent much of his life observing Vesuvius near Naples, where he taught at the University of Naples. He is the inventor of an alternative to the Richter scale for measuring the intensity of earthquakes.

Unlike the Richter scale, which measures the power of earthquakes, the Mercalli scale pinpoints the effects on human habitation. A modified version of his scale is still in use by the U.S. Geological Survey. For example, an earthquake registers at a 2 on the Mercalli scale if it was “felt only by a few persons at rest, especially on upper floors of buildings.” A 10 on the scale means that “Some well-built wooden structures destroyed; most masonry and frame structures destroyed with foundations. Rails bent” (source: U.S. Geological Survey).

Born in 1850, Giuseppe died in his apartment in a fire 1914. At the time of his death, he was an internationally known scientist, earning a three-page story in the New York Times. Given the suspicious nature of the blaze that had claimed his life, the Times raised the possibility that he had been murdered (according to this source).

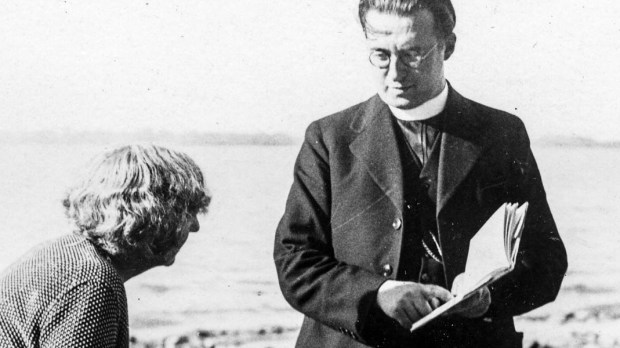

Fr. Georges Lemaitre

Given contemporary stereotypes about the incompatibility between faith and science it might come as a surprise to some people that the man who developed the Big Bang theory—the basis for the current scientific model of the universe—was a Belgian Catholic priest named Georges Lemaitre.

Born in 1894, Lemaitre studied civil engineering at the Catholic University of Louvain and went on to serve in the artillery division of the Belgian military during World War I. After the war he entered the seminary and was ordained a priest in 1923. He continued his studies in physics at the University of Cambridge. He also studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Building upon astronomer Edwin Hubble’s observations about the expansion of the universe and Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, Lemaitre hypothesized that the universe had begun from a dense starting point that he dubbed the “primeval atom” or the “cosmic egg.”

The Big Bang theory, as it came to be known, challenged Einstein’s own view of a static universe. The famous scientist told Lemaitre that “Your math is correct, but your physics is abominable.” When Lemaitre’s theory was later confirmed by observation, Einstein recanted his view and reportedly declared that Lemaitre’s theory was “the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of creation to which I have ever listened” (sources here and here).

Lemaitre died in 1966. His Big Bang theory, in modified form, remains the basic model cosmologists use to describe the universe today.

Fr. Stanley Jaki

Stanley L. Jaki was a Hungarian-born Benedictine priest who wrote extensively on the relationship between science and faith. Born in Gyor, Hungary in 1924, he became a priest in 1948, and received his doctorate degree in theology from the Pontifical Institute of St. Anselm in Rome two years later.

Jaki started teaching, but then had to leave his work after a tonsillectomy left him unable to speak. So he returned to school to study physics, earning his doctorate at Fordham University under Victor F. Hess, who discovered cosmic rays. Jaki returned to teaching at Seton Hall University as a professor of physics, a position he held until his death in 2009 at the age of 84.

His obituary in the New York Times describes him as a “relentless scholar” who produced more than 40 books over the course of his career, including studies of G.K. Chesterton and Cardinal John Henry Newman.

Among his more notable works were The Relevance of Physics in 1966 and Science and Creation in 1974. In both works, Jaki “argued that the scientific enterprise did not become viable and self-sustaining until its incarnation in Christian medieval Europe, and that the advancement of science was indebted to the Christian understanding of creation,” according to the Times. In a 1967 article in the Journal of Science and Religion, Jaki advanced his argument even further, stating that “faith, or belief, forms the ultimate foundation of the certainty of every knowledge.”