Pentecost delivered the gift of tongues soon after Jesus had proclaimed: “… go and make disciples of all nations.” The paradox is how little recognition goes to the evangelist who used his powers of communication to take the message further than anyone else.

Eight days after Jesus met his disciples following the Resurrection, he encountered St. Thomas. Since then, St. Thomas the Apostle has been better known as Doubting Thomas. His least-used title is “Apostle of India.” In the Subcontinent, the situation is very different. There, even the vast non-Christian majority of 1.7 billion are mostly aware of his role as missionary extraordinaire.

When Vasco da Gama’s fleet reached India in 1498, the Portuguese were surprised to find Christian communities thriving in the south of the Subcontinent. They were even more surprised by the locals’ certainty that their church had been established by St. Thomas. They shouldn’t have been, as countless travellers, including Marco Polo, had claimed that the saint’s grave was there. St. Thomas had preached to the Hindus and the Jews of southern India and had won thousands of converts. For the St. Thomas Christians, there is still no doubt that theirs is an unbroken tradition going back to their patron’s arrival in 52.

Click “Launch a slideshow” in the image below:

There has been a revival of interest in St. Thomas’s path through the Middle East, with the continuing plight of Christians in Syria and Iraq. Further east than that, however, the co-religionist radar is picking up almost nothing. A recent book by one of the most enterprising travelers of present times might help western Christians look again at the development of their faith.

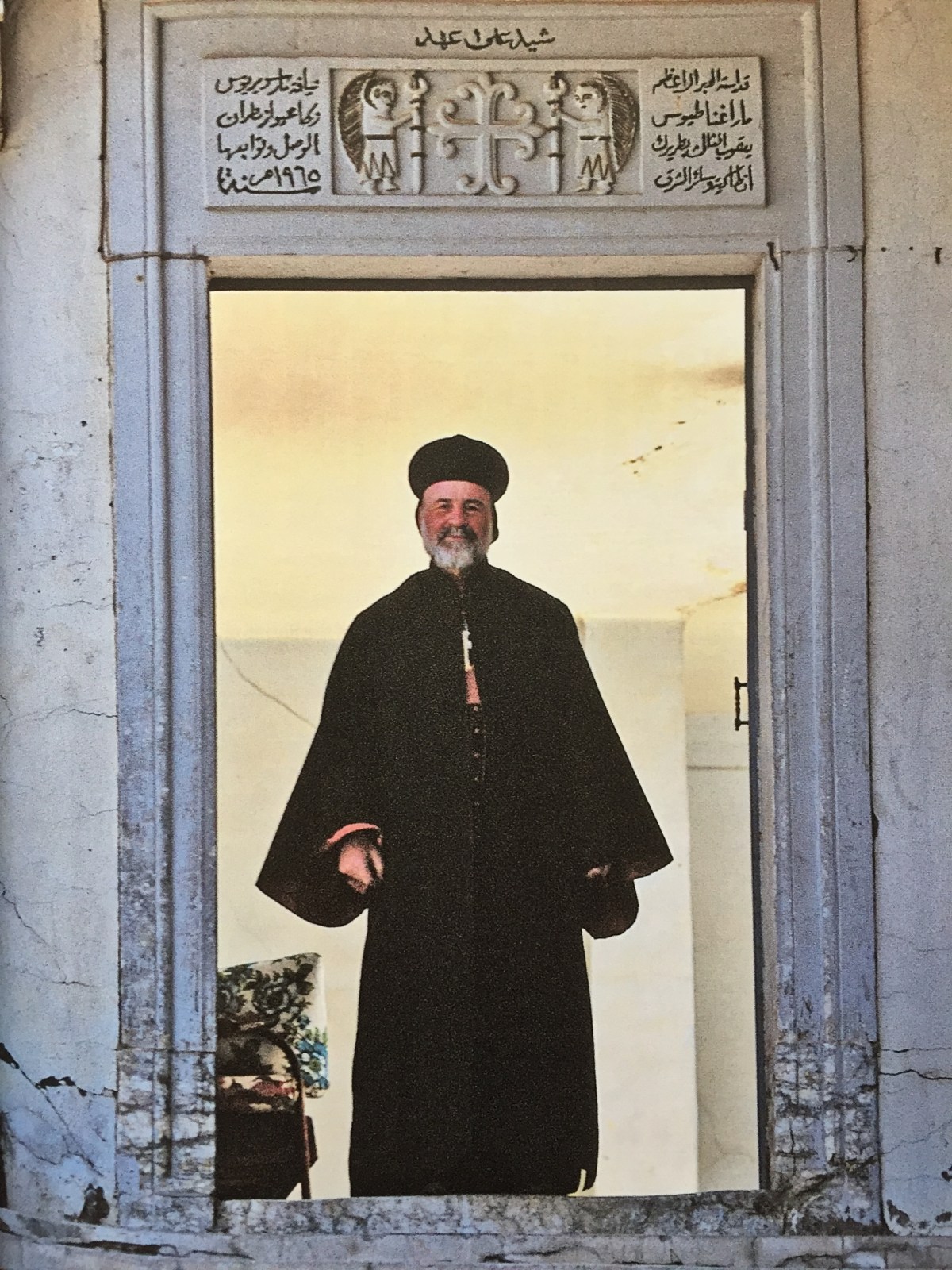

Serena Fass is an 80-year-old writer, photographer and wanderer who has followed St. Thomas’s progress across much of Asia. Her book In the Footsteps of St. Thomas corroborates the evidence that has existed for centuries. This does not come from the Bible or other texts that historians find unreliable, although written sources described his travels as long ago as 1,800 years. On-site investigation is the new key to unlocking the truth about St. Thomas.

There are few Christian communities that go back to the time of Jesus’s disciples. Serena Fass finds much to support the beliefs that the faithful in India hold firm to, although there are still plenty who dispute them. In those pioneering days, India was the magnet that drew Europe to the East. When Columbus chanced upon what was later called the West Indies, it was India he thought he had reached. India was the trading world’s most profitable destination.

The evidence of Thomas’s presence in India is considerable. Some of it stretches the imagination while the rest is at least as plausible as the Turin Shroud, albeit with less publicity. Keeping a low profile has been the secret of survival. Levels of hostility to Christians in India are on the rise, and the belief that St. Thomas was martyred by either a local ruler or a Brahmin priest hardly lessens what is considered by some Hindus to be a blood libel.

St. Thomas’s tomb is less conspicuous than that of other Apostles to be honored with a basilica. His original south Indian resting place was not in a Christian stronghold, and he was buried without much ceremony. Most of his bones were removed from India in the 3rd century and sent to Edessa in Mesopotamia, where the saint’s vital role in India was acknowledged at the time. Once again the bones’ progress is followed across the globe by Serena Fass as they eventually end up in the Italian town of Ortona.

The Catholic Church maintains a neutral stance on the proposition that Christianity might have been established in India long before it was in most of Europe. There is more evidence of St. Thomas’s life in India than anywhere else; in 1956 Pope Pius XII granted minor basilica status to San Thome Cathedral in Madras.

Serena Fass has collated traditions handed down over almost 2,000 years, along with a physical trail that includes some very old Crosses. The “Thomas Christians” of India use a Cross of distinctive shape. Crucifixes are rare, as would be expected of a community that started long before the Corpus became an accepted part of Christian imagery.

Relics of St. Thomas are less common than his tombs, of which there are purportedly six. A fascinating reliquary exists in Mylapore. Originally housing some of the saint’s bones, it is now empty. The decoration tells a heartening story of coexistence in India. With decoration in Hindu style, probably by Muslim craftsmen, on a Christian theme, it is a testament to Indian multiculturalism. The only thing missing is a Jewish element; it is known that the earliest converts to Christianity in southern India were, like Thomas himself, Jews. This is part of the Diaspora that tends to be as forgotten by the Jewish community as St. Thomas of India is by Christians around the world.

Even if every other part of the St. Thomas story is one day proved to be false, there can be no doubting the Thomas Christians’ incontrovertible inks with Syrian Christianity. In southern India they still use the liturgical Syriac language — a dialect of the Aramaic language spoken by Jesus and St. Thomas. Syria was the bedrock of early Christianity and an important part of the Roman empire, trading with southern India from the Red Sea. This was inevitable for the Romans, with their addiction to pepper and knowledge of monsoon winds. Roman coins and other evidence is found in abundance. In the 1930s one of Britain’s greatest archaeologists, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, even found the remains of a Roman trading post.

At a time when the earliest Christian communities are being eradicated in the Middle East, their legacy at least lives on in India, thanks to St. Thomas.

‘In the Footsteps of St Thomas’ is available through Aid to the Church in Need UK, a Catholic charity dedicated to helping the persecuted and oppressed, and through Amazon in the US.