A symposium is concluding today in Rome, marking the 20-year anniversary of the opening of the archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which famously includes historical documents from the Roman Inquisition.

Opening these documents, the then-Cardinal Ratzinger believed, would mark “a new stage” in the dialogue between the Church and the people of today.

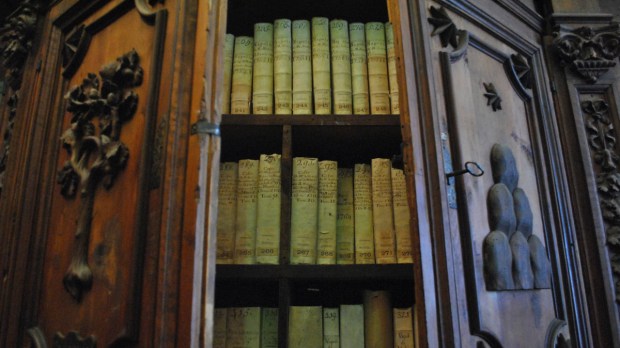

These archives, which cover the years 1542-1903—held in 4,500 volumes—trace four centuries of Church history, although a large part of the archive has disappeared.

Monsignor Alejandro Cifres, who is in charge of the archives, said the documents show that the Inquisition does not match up to its “black legend.”

Here is our interview with Msgr. Cifres:

What do these archives reveal about the Inquisition?

The archives show that the truth is different from the usual image of the Inquisition. The black legend is a legend, as are the “rose-tinted” legends that try to justify everything. I always say that no researcher has ever come to see our archives for the first time and left with an even worse idea of the Inquisition!

These archives highlight that the Inquisition was a man-made institution according to criteria different from ours, but that sought to apply norms and rules with rigor and seriousness. Above all, the Inquisition was not only a court that tried and condemned—and often absolved; it was above all a place of discussion where ideas were studied, and where doctrines were explained.

The images of a witch-hunting court are caricatures, and whoever comes to the archives will realize it. Serious historiographers did not have to wait for the archives to be opened to realize it.

What is the Inquisition?

First of all, we have to know that there were three different inquisitions. First, there was the medieval inquisition, which was a prerogative of bishops or papal delegates for particular cases. The most famous episode is the crusade against the Albigenses in the 13th century.

Then, there were the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions, which were the first to be centralized at the level of a country.

Finally, there was the Roman Inquisition, founded in 1542 by Paul III to be a central organ of the Holy See to control religious dissent. Since it was pontifical, it had universal jurisdiction; that is, it covered the whole world. In fact, it did not act in the territory of the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions, and therefore it did not act in the Americas either. In 1908, the Roman Inquisition gave way to the Holy Office, itself a predecessor of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Why did Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then prefect of the Congregation and future Pope Benedict XVI, want to open these archives?

Until 20 years ago, our archives remained largely closed to consultation. It was the last Vatican archive area never to have been opened; most had been open at the end of the 19th century. In 1998, Cardinal Ratzinger, after several requests, decided that the time was ripe to open them to researchers. Anyone who has a recognized diploma certifying that they are capable of reading these documents—and not just those moved by curiosity—can come to the archives. There is no discrimination of ideology, religion, or nationality.

As an archivist, I can say that the record is very positive, especially for the climate of collaboration that emerged between the institution and the academic world.