To this convert from evangelical Protestantism, icons of Mary had long exuded a kind of strangeness, but this one was the strangest of all.

I was in the Russian Icon Museum in central Massachusetts, on assignment for a travel article, and had seen the increasingly familiar parade of Theotokos icons, usually depicting Mary with her head bowed in devotion, with the smaller Christ child cradled in the center of the image. I had taken time to pause over a row of icons showing the Anastasis or descent of Christ to hell. But this icon, on first glance, was completely inexplicable.

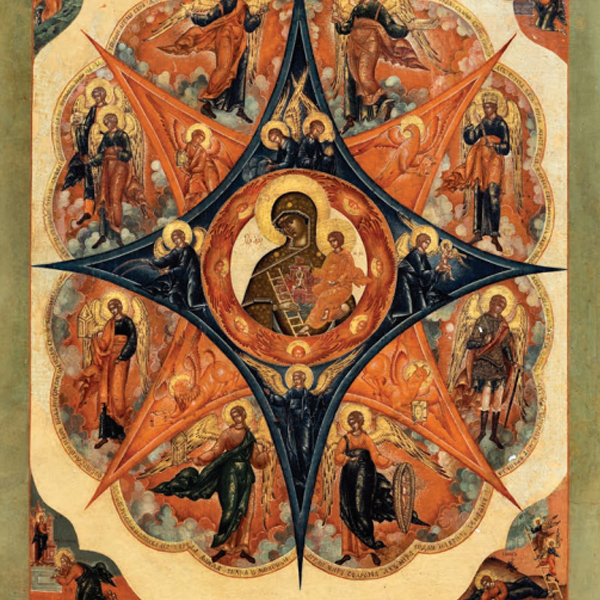

The icon (pictured above) has two giant stars spread over it. The center of each star is over the other with their beams pointing out in different places. Each star has four “spokes,” as one writer puts it. One star is blue; the other is read. In the center, where the light would be brightest is the Virgin with Christ. In most icons, Mary looms large, her head bowed ponderously. Here she is much smaller and so is Christ, relative to her and the icon as a whole. The spokes and clouds around the star are filled with various angelic or saint-like figures. In the corners are four narrative scenes.

What is going on here?

The title of the icon is the Mother of God of the Unburnt Bush. Many Catholics are familiar with the many women of the Old Testament who prefigure Mary, like Eve or Hannah. But the burning bush? That’s probably a new one to many of us. It certainly was to me. The association between the two is deeply rooted in the Eastern Orthodox liturgy. Take these lines from the Akathist Hymn to Mary:

The great mystery of your childbirth did Moses perceive within the burning bush. The youth vividly prefigured this, standing in the midst of fire and remaining unconsumed, O undefiled and holy Virgin. We praise you therefore in hymns to the ages (Ode Eight, The Eirmos).

The same idea inspired a Coptic hymn, titled the Burning Bush:

The Burning Bush seen by Moses The prophet in the wilderness The fire inside, it was aflame But never consumed or injured it The same with the Theotokos Mary Carried the fire of divinity Nine months in her holy body Without blemishing her virginity

The icon, according to a paper at the icon museum, can be traced back to the St. Catherine Monastery in Egypt, located at one of the traditional sites of the burning bush. The monastery itself dates back to the earliest centuries of Christianity, although it’s unclear how early the icon of the burning bush appeared. But the theological foundation for the idea goes back to a Church Father of the 300s, St. Gregory of Nyssa, who made the following observation in his treatise on the Life of Moses:

From this we learn also the mystery of the Virgin: The light of divinity which through birth shone from her into human life did not consume the burning bush, even as the flower of her virginity was not withered by giving birth (2.21).

Gregory of Nyssa is a Greek Father whose influence spans both sides of the East-West divide. So it’s not surprising that we see some identification between Mary and the burning bush in Western art as well, even if it’s less commonplace. For example, there is this Triptych of the Burning Bush, by Nicolas Froment in the Aix Cathedral in southern France. And there is also the mosaic in the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception that pairs the Annunciation with the burning bush. (These sources, here and here, respectively, pointed me to these images. The former also introduced me to the Coptic hymn.)

All of those clearly have recognizable bushes in them along with the Virgin. Another example is here. But the burning bush icon at the top of this page does look anything like these images. There is no bush and no obvious flames.

One of the visual ties between the icon and the burning bush seems to be the star itself—representing the divine uncreated light that settled upon the bush, according to Orthodox tradition. In this interpretation, what is most significant about what happened on the mountain is not so much that the bush was burning but that it radiated the divine light.

The paper on the icon published by the Russian Icon Museum also suggests that the red star signifies the burning of the bush. This is possible, but there is an alternative explanation, one made more likely by the accompanying blue star. Blue is a symbol of royalty, and, by extension divinity (as this iconographer explains it). Hence, it would make sense if the blood-red color was representative of Jesus’ humanity. We often see this pairings of colors in icons of Christ (see here, for example).

The red and blue stars, then, are emblematic of the divinity and humanity of Christ. The icon is emphasizing the truth of the Incarnation, and, in particular, how this truth shone out from Mary, much like the fire in the burning bush many centuries earlier.

But what about the rest of the icon? Every part of it, it seems, is saturated in symbolism.

First of all, notice how in the very center we have not only Mary and Christ but a few other images as well. In the center left Mary is holding Jacob’s ladder, reflecting the Orthodox belief that she was the “ladder” by which one ascended to God. (My main source for the identification most of the symbols and figures in the icon from this point on is the museum’s explanatory paper. Another source consulted is here.)

The angels in the mandorla could be the seraphim spied by Isaiah in his vision of the heavenly altar, which would be fitting since it is at the altar where both the ancient Israelites and Christians today encounter God most directly. Given that other versions of this icon display seraphim as well, this interpretation is probable. Moreover, the seraphim are also in the upper right corner of this icon, further supporting this conclusion (more on that below).

Within the four spokes of the red star are the four evangelists. Clockwise from the top left spoke they are: the man as Matthew, the eagle as Mark, the ox as Luke, and the lion as John. (This mixes up the traditional imagery a bit, in which John is usually the eagle and Mark is the lion.) It is fitting that the evangelists would be in the red star: their gospels tell the story of the Incarnation—the taking on of flesh by God.

The four blue spokes contain angels who control some of the airborne elements of the earth—the clouds, rain, and wind. The fourth has a horn. There are multiple possible interpretations of this. Given that blue is the color of divinity, one possible one is that the cloud is the one that settled on Sinai and the cloud of the Holy Spirit that “overshadowed” Mary. The wind then could designate the Holy Spirit.

Finally, it’s worth noting that we have a total of eight spokes, with eight being a number of eternity in Scripture, according to the icon museum. But the number eight has other meanings as well. In particular, it is connected with the idea of new creation. It is also happens to be how many writers there were in the New Testament (source here). The new creation theme certainly fits in with an icon devoted to Our Lady and Christ. And, for the same reason, so does the link to the New Testament, especially given that four of those eight writers are in this icon.

As we move outwards from the center, we observe four patches of clouds. Each of these is occupied by angels, most of them known mainly in the Orthodox tradition. For example there is Selaphiel, which means the Prayer of God, equipped with a boat-shaped censor known as a navicular, and Uriel, The Light or Fire of God, armed with a flaming sword.

Finally, the four corners of the icon are adorned with relevant scenes from the Old Testament. Clockwise from the upper left we have: Moses and the burning bush, Isaiah’s vision of the seraphim in the heavenly temple, Jacob’s dream of a ladder, and Ezekiel’s vision of the temple. All four scenes emphasize how God makes use of physical realities to manifest Himself to mankind. Mary, of course, is the culmination of this development.

The burning bush that called out to Moses was among the most mysterious of God’s manifestations in the Old Testament. This icon reminds us that we can enter into this same mystery through Mary.