Even saints of the moral stature of Mother Teresa of Calcutta, admired by believers and non-believers alike, bear witness to having suffered trials that seem surprising, maybe even shocking. To anyone who thinks the saints lived in a bubble of perfection, removed from the daily circumstances that affect “ordinary” human beings, there’s this: the “dark night of the soul.”

The most famous treatise on the subject is probably written by Spanish mystic and Doctor of the Church, St. John of the Cross. He describes that profound kind of spiritual crisis on the road towards a union with God in his famous poem from the 16th century titled “The Dark Night of the Soul.”

The fact is, with certain frequency God allows an intense trial of spiritual aridity, of complete lack of sensible fervor, of doubts regarding His existence, of outrage at the injustices of life, of despair in the face of tragedy, or desperation with the routine which, day after day, month after month, takes on an insufferable and amorphous lack of meaning…

If Christ Himself experienced the drama of the silence of the Father during the darkest of nights, to the point of begging His Father to take that chalice away from Him during His prayer in the Garden of Olives in preparation for the Passion, why should we assume that God would spare us from experiencing radical doubt? Why should we imagine that he would deny us the opportunity of choosing, freely and voluntarily, to embrace the faith or reject it, to trust in Him or reject Him, to purify our love or keep it tepid, fragile, compromised by comfort or by weak incentives?

Not even the vocation to the religious life exempts a Christian from spiritual trials.

It’s clear that these trials aren’t always the physical and psychological suffering that today we know as depression. Nonetheless, there are saints who, based on the symptoms they themselves or their biographers describe, very probably faced this syndrome, which today is seen as “the disease of the century.”

Here are some of the saints who may have suffered some degree of depression during their earthly lives …

1. St. Augustine

4th century

One of the most iconic and sublime figures representing the intensity of Christian conversion and the extraordinary power of sanctifying grace — one of the most admired personalities in the history of Western civilization, even by non-Catholics and non-Christians — faced, very probably, the ups and downs of neurotransmitters and the psychological and physical instability which today’s medical world calls depression.

His mother, St. Monica, supported with almost unbelievable patience the unpredictability of her son, who was brilliant but had a challenging temperament. Augustine searched for the truth and for the meaning of existence with intense sincerity. However, in his disoriented journeys (as he describes them in his own words), he sought them in the appearances of created things, in lust and the pleasures of the senses, far from God and farther and farther from himself. “You were within me, but I was outside, and it was there that I searched for you. In my unloveliness I plunged into the lovely things which you created,” he declared in his Confessions, a masterpiece not just of Christian spirituality, but of universal spiritual literature.

The stubbornness of grace, however, was even more persistent than Augustine’s own. That grace, finding a channel in the indefatigable prayers of his mother and the admirable influence of the great bishop St. Ambrose, carried the rebellious and angst-ridden Augustine to finally surrender to God and choose baptism. And not only that: he consecrated himself to God, and was eventually made a bishop.

After his mother died, and during the more than 40 years that followed, Augustine’s powerful personality would still manifest itself frequently in a propensity to implacable anger and to … severe depression. He lifted himself up from those abysses by means of prayer, sacrifice, and work. Keeping himself busy was a great remedy, both in his many responsibilities as a bishop and in his many hours of reflection, study, and prayer that transformed him into a great defender of Church doctrine.

2. St. Flora of Beaulieu

14th century

Flora had a normal childhood, but when her parents began to look for a husband for her, she refused, and announced she was going to dedicate her life to God by entering a convent. This decision, made in the midst of a turbulent situation, set off an intense and prolonged period of depression, which affected her behavior so much that living with her was a trial, even for the other sisters.

But with the grace of God, with time, and with the help of an understanding confessor, Flora made great spiritual progress precisely because of the challenge of depression, which she faced with strength of will.

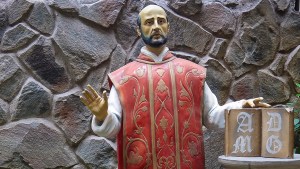

3. St. Ignatius of Loyola

16th century

The powerful personality of the great and saintly founder of the Jesuits was also given to deep feelings of unrest and suffering. The certainty and conviction that he reveals in his autobiography (written in third person) didn’t come easily. After his conversion, Ignatius had to fight against a period of intense scrupulosity, a term which, in Christian ascetics, refers to the temptation to feel oneself always in a state of grave sin for every tiny personal failing in fulfilling one’s duties in living the virtues. That trial was followed by a depression that was so serious, he even thought of suicide. God saved him from the abyss of darkness and interior suffering, inspiring him to do great things with his life in the name of Christ and His Church.

Ignatius himself, in his Spiritual Exercises, calls the experience “desolation”: a state of great unrest, irritability, discomfort, insecurity regarding oneself and one’s own decisions, frightening doubts, great difficulty persevering in good intentions … According to Ignatius, God doesn’t cause desolation, but He allows it to shake us awake to our condition as sinners and to call us to conversion.

Based on his experience, St. Ignatius gives three pieces of advice for reacting to desolation: do not desist, nor alter a previous good resolution; intensify your conversation with God, your meditation, and good works; and persevere with patience, because the trial is strictly limited by God, who will give you relief at the opportune time. He discovered, in short, that depression can be a great spiritual challenge and a great opportunity for growth.

This advice continues to be perfectly valid, but today, it’s of crucial importance to add a fourth counsel: obtain proper medical help. Medical progress has made it clear that, in most cases of true depression, psychiatric medicine is indispensable for restoring the balance of neurotransmitters, because depression is an illness properly speaking, and not just a “sad phase.” The treatment of clinical depression involves two interdependent approaches: a personal interior approach, which can be accompanied by a good psychologist or a qualified counselor; and medical treatment, under the guidance of a serious psychiatrist who is up to date in the field.

Read more:

4 Ways St. Ignatius can help you grow in emotional intelligence

4. St. Jane Frances de Chantal

16th century

For eight years, Jane lived happily in her marriage with the Baron of Chantal. However, when her husband died, her father-in-law, who was vain and stubborn, forced Jane and her three children to live with him, creating a situation of constant conflicts, difficult trials on her patience, and … depression. Instead of taking refuge in playing the victim, St. Jane chose to keep smiling and to respond to her father-in-law’s cruelty with charity and comprehension.

Even after establishing a cordial and holy friendship with the great bishop St. Francis de Sales, and working with him to create a religious order for older women, Jane continued experiencing moments of great suffering and of being judged unjustly — and she also continued to respond with a smile, with hard work, and with a spirit turned towards God.

In this regard, St. Francis de Sales has some relevant advice for those who suffer from that kind of trial:

“Refresh yourself with spiritual music, which often makes the devil stop his tricks, as in the case of Saul, whose spiritual evil left him when David played his harp before the king. It is also useful to work actively, and with as much variety as possible, so as to distract your mind from the cause of your sadness.”

5. St. Noel Chabanel

17th century

A Jesuit priest and North American martyr, Noel worked among the Hurons with Saint Charles Garnier. In general, the missionaries developed great empathy for those whom they were evangelizing; however, that was not the case for Fr. Noel: he felt revulsion towards the Native Americans and their customs, in addition to the great difficulty he experienced in trying to learn their language, which was completely different from any European language—not to mention the brutal challenges involved in their life in that nearly savage environment. All of these trials put together caused in him a lasting sentiment of spiritual suffocation. How did he respond? By making a solemn vow never to desist nor abandon his mission. He kept that vow until his martyrdom.

6. St. Elizabeth Ann Seton

18th century

The first saint born in North American suffered from a constant feeling of loneliness and melancholy, so profound that she thought several times of suicide. She faced many problems during her life, especially regarding her family; her beloved husband died young and in financial ruin, and when she converted to the Catholic faith, many of her family and friends rejected her. Reading, music, and the sea helped her feel happier. After her conversion, the Eucharist and charity became her source of daily strength. Before she died at the age of 46, she had founded a religious community, a school, and two orphanages.

Read more:

The unbreakable St. Elizabeth Ann Seton can help us shift our perspective upwards

7. St. John Maria Vianney

19th century

Known as the Curé D’Ars (“the parish priest of Ars”), John of Vianney is one of the most beloved priests in the history of the Church, a model of a zealous pastor who overcame his many and significant intellectual limitations in order to guide souls masterfully along the path of the life of grace. Despite all the good he did, he couldn’t manage to see his own relevance before God, and lived constantly with an intense inferiority complex, considering himself to be useless—a symptom of depression which would accompany him throughout his entire life.

During times of difficulty, he would turn to the Lord and, despite his suffering, would renew his determination to persevere in his work with trust, faith, and love for God and neighbor.

8. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein)

20th century

This saintly Descalced Carmelite, who was born Jewish and grew up as an atheist, suffered depression for a long time. At one point, she wrote:

“I gradually worked myself into real despair … I could no longer cross the street without wishing that a car would run over me … and I would not come out alive …”

Edith suffered intense depression, starting before her conversion, principally on the many occasions when she was scorned and humiliated because she was of Jewish origin and a woman. An intellectual, a philosopher,and a disciple and assistant of renowned philosopher Edmund Husserl (founder of the philosophical school of phenomenology), she finally found in God the Truth she sought for so earnestly, thanks to reading the works of St. Teresa of Jesus. She then embraced God’s grace with such totality that it gave her the strength to deal not only with her intense interior sufferings, but also with the deadly darkness of Nazism.

After her conversion and radical consecration to God as a Descalced Carmelite, Edith Stein took the religious name of Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She was able to persevere to the point of martyrdom, keeping her clarity of mind, her faith, her hope, and her love even in prison and in the face of the execution she suffered at the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Does that end of her earthly life seem particularly depressing? Well, yes it is. Nevertheless, like everything in this life, there’s more than one side to it. She faced that extreme situation with the serenity and peaceful soul of someone who learned to deal with the ups and downs of depression, seeing beyond the immediate, and embracing a life that never ends, because it is eternal—and which is able to shine even in the deepest darkness of death in a concentration camp.

Read more:

Depressed? Here’s a patron saint for you

Read more:

J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic cure for frustration, depression, and doubt