Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Is it a sin to say “I just can’t take it anymore!”?

Well, it depends …

Here I suspect that my scrupulous friends are now putting fresh batteries in their “Grave Matter Detectors” (part of the “Save-Yourself!” set of accessories from Jansenists-R-Us, Incorporated), ready to hunt for mortal sin. Yet, when we look at the darkness swirling around us and the darkness churning within us, is it really unreasonable to say, “I just can’t take it anymore!”?

Most of us have friends now caring for dying spouses, friends diagnosed with cancer, friends nursing gravely ill infants, friends with broken hearts, friends abandoned by spouses, friends mourning their beloved dead. Haven’t we looked at headlines announcing the latest calamity in the Church or the world, and asked, “How can I go on?”

There are limits to our endurance, whether physical, mental, or emotional. Long-distance runners speak of “hitting the wall,” when they reach the limit of their capacity to take another step. Can’t we “hit the wall” in the spiritual life? Isn’t there a point where we just can’t be expected to make another act of faith, hope or charity?

Well, it depends …

Thinking too much of ourselves and our abilities, we’re guilty of presumption. Thinking too little of ourselves and the abilities and graces God has given us, we’re guilty of pusillanimity (best translated as “smallness of soul”—the opposite of magnanimity). Resentful that the spiritual life is difficult, we’re guilty of acedia (inadequately translated as “sloth”). And if we believe that God won’t fulfill his promises, we’re guilty of despair.

Read more:

A prayer for the days you just can’t take it anymore

Sometimes, God needs to purge us of our illusions about ourselves, so that we can then be purged of our illusions about him. Then, with nothing but the truth about ourselves and God, we can become holy.

Here’s an example. One of my Jesuit heroes is Father Walter Ciszek. (Please read his books, With God in Russia and He Leadeth Me.) Captured by the KGB in 1939, he spent five years in Moscow’s notorious Lubianka Prison. His tormentors had prevailed upon him to confess that he was a Vatican spy. Threatened with immediate execution, he gave in and signed the false confession. Father Ciszek later wrote that as he signed the papers, he said of himself: “I began to burn with shame and guilt. I was totally broken, totally humiliated … I felt guilty because I … had asked for God’s help but had really believed in my own ability to avoid evil and meet every challenge.”

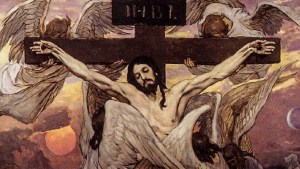

For four more years, Father Ciszek’s tormentors tried to force him to become a Soviet spy within the Vatican. On the brink of despair, he recalled the agony of Our Blessed Lord in the Garden of Olives. Then he underwent what he described as “a conversion experience.” He wrote of himself: “I was brought to make this perfect act of faith, this act of complete self-abandonment to his will, of total trust in his love and concern for me and his desire to sustain and protect me, by the experience of my own powers and abilities.”

If we’re to say and mean, “Jesus, I trust in you,” we must also admit that we’re at that moment also saying, “Jesus, I don’t trust in myself.” I think that Father Ciszek would agree, for, reflecting on his own experience, he wrote these words: “… just as surely as man begins to trust in his own abilities, so surely has he taken that first stop on the road to ultimate failure. And the greatest grace God can give such a man is to send him a trial that he cannot bear with his own powers—and then sustain him with his grace so he may endure to the end and be saved.”

We might be tempted to dismiss such words that are at once both sobering and hopeful. Yet we dare not dismiss the wisdom of a man who had been to hell and back again. This noble Jesuit was pruned severely, stripped of all illusions, brought to the brink of despair, and, humanly speaking, had every “good” reason to cry out: “I just can’t take it anymore!” Yet, when he was about to go under, he grasped the strong hand that was offered to him.

What can we learn from this?

So many of us keep ourselves frantically busy, desperately distracted and willfully overmedicated, because we can’t accept the truth about our own human limitations, and we can’t accept the promises of the infinite God. Walter Ciszek shows us that our weakness need not be a cause for sin or shame, if we turn to God who would be our strength, our shield and our salvation.

When I write next, I will speak about the healing power of innocence and the Eucharist. Until then, let’s keep each other in prayer.

Read more:

Jesus said there is no better novena than this one, and it has only 11 words