Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

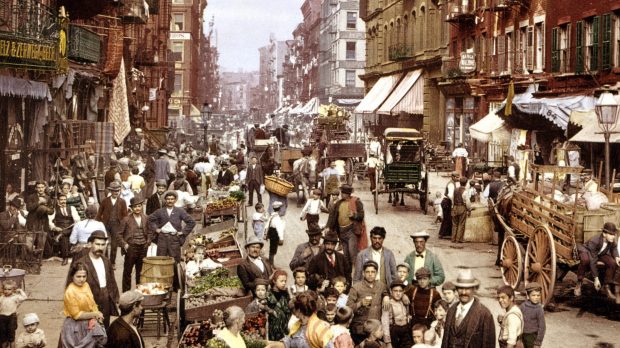

In the early 1800s the two largest Catholic communities in New York, the Irish and the Italian, hated each other to the bone. It was not uncommon for fights to break out in the streets, on construction sites and even on church grounds.

The animosity was such that an op-ed from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a local newspaper, read: “Can’t they just be separated?” with “they” being Italian and Irish men working, and fighting, on a construction site in Brooklyn.

The Church was not spared from this antipathy. When Mother Francis Xavier Cabrini traveled from Italy to New York in 1889 with the mission of catering to Italian children, Archbishop Michael Corrigan, who was born in New Jersey from Irish immigrants, advised her to go back to Europe.

Mother Cabrini ended up staying and helped set up many institutions that improved the life of immigrants—from orphanages to schools and hospitals. But her unfriendly welcome is telling of the anti-Italian sentiment that permeated much of the American Catholic Church at the time. Indeed, Pope Leo XIII dedicated an entire encyclical to this problem—“On Italian Immigrants” (1888)—asking American bishops for better treatment of his compatriots.

As explained by New York journalist Paul Moses in his 2015 book An Unlikely Union, part of the reason why Irish clergymen disliked the Italians had to do with the political struggle taking place in the old continent. The ongoing Italian unification process meant that many lands that had been owned by the pope were suddenly claimed by the newborn Italian state. Many Irish sided with the pope and hated the Italians as a result.

But then, slowly but steadily, the two enemies started to find some common ground. As Moses explains, the pacification of these two feisty communities was fueled by three main factors. First, Italians eventually established themselves economically—so the Irish started to perceive them as equals. Of course, this was not a smooth process as it entailed an economic battle between the two migrant groups. Irish workers hated the Italians for “stealing their jobs” by offering to perform tasks like bricklaying for a cheaper price—a tactic that bore its fruits. In 1883, three quarters of New York construction laborers were Irish. A decade later, the majority of the labor force in the same sector was Italian. But as the Irish gradually moved to more skilled occupations, like carriers and providers of building materials, they eventually learned to tolerate the (less skilled) Italian workers.

Transport innovations such as the subway provided another important catalyst for integration. As Mason explains, previously enclosed ethnic groups started to spread around the city—and mingle. It was through such mingling that one of the most strong pacifying forces was unleashed: romance. At the start of the 20th century Italians and Irish started to marry each other and the number of intra-ethnic unions peaked in the years after World War II.

As Moses observes, most of the Italian men who married Irish women were church-goers and attended Catholic schools, suggesting that a common religion played a big role in many of these these “unlikely unions.”

Some of the most prominent Irish-Italian couples include Italian mob leader Al Capone and Mae Josephine Coughlin, who was born to Irish immigrants in Brooklyn. The two got married at St. Mary Star of the Sea Church in Court Street, Brooklyn, on December 18, 1918. For a long time, Mae was allegedly unaware of Al’s unlawful activities, which eventually included fighting against the Irish mob for primacy over bootlegging activities.

Moses also features the union between Irish labor leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Italian anarchist Carlo Tresca, who met in the streets of Lawrence, Massachusetts, during the Bread and Roses strike of 1912. Flynn and Tresca were both married but started a turbulent love affair that, due to their political undertaking, was often the subject of yellow press stories.

By the mid-1960s Irish-Italian unions were increasingly common and Moses himself is the son of an inter-ethnic marriage.

Despite many blossoming romances, the two communities maintained a good dose of healthy competition, which is perhaps best epitomized by the relationship between Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, who engaged in playful banter throughout their careers. Both were sons of immigrants, neither had any serious musical training and yet, like many other of their Italian and Irish peers, they left an indelible mark in what the world got to know as “American culture.”