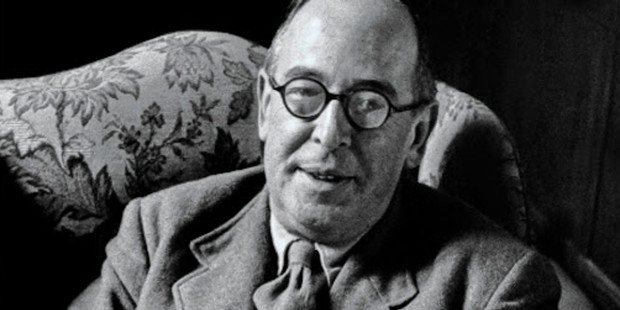

“I think our business as laymen is to take what we are given and make the best of it,” C.S. Lewis wrote in his last book, Letters to Malcolm. This astonishingly smart man, a man who was among the best in the world at what he did, taught humility when looking at himself as a mere Christian. That would be his first lesson about worship.

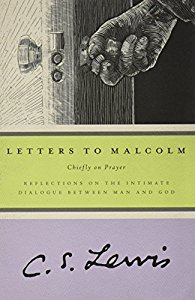

Letters to Malcolm is a rich book, and fun to read. Subtitled “Chiefly on Prayer,” it appeared in 1964, a few months after Lewis died.

The friend is made-up as a reason to write in a simple, personal way about prayer and related matters. It’s Lewis at his best, I think.

The 32 letters express not only three decades of sacrificial Christian obedience, but the searing pain of losing his wife three years before. I wish the book were better known.

The old shoe

Lewis taught humility, but he expected something from ministers. Somewhere else he speaks of the church as a dance and in a dance both partners have to do their part.

He was a member of an unusual Protestant body, the Church of England. Being the country’s national church, it included people who were practically Mennonites and people who would have been considered extreme in Renaissance Rome. You could feel a kind of liturgical whiplash going from church to church.

Laymen like himself could find taking what they were given “a great deal easier if what we were given was always and everywhere the same.” He was a little grumpy about this. Ministers in his church thought “people can be lured to go to church by incessant brightenings, lightenings, lengthenings, abridgements, simplifications and complications of the service.”

He explains why we need things to stay the same. “Novelty, simply as such, can have only an entertainment value. And they [we laypeople] don’t go to church to be entertained.” The people “go to use the service, or, if you prefer, to enact it. Every service is a structure of acts and words through which we receive a sacrament, or repent, or supplicate, or adore.” The service does this best when,

through long familiarity, we don’t have to think about it. As long as you notice, and have to count the steps, you are not yet dancing but only learning to dance. A good shoe is a shoe you don’t notice. Good reading becomes possible when you need not consciously think about eyes, or light, or print, or spelling. The perfect church service would be one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.

Read more:

Must worship be entertaining?

It takes all sorts

At the same time, Lewis loved the differences he saw among Christians, including differences he saw at worship. “It takes all sorts to make a world, or a church,” he tells Malcolm. “If grace perfects nature it must expand all our natures into the full richness of the diversity which God intended when He made them, and heaven will display far more variety than hell.” That’s a big point for Lewis, that holiness makes us more ourselves and sin makes us less ourselves, that is, dull and boring. Holiness makes the world more interesting.

Our worship should express this. He continues: “What pleased me most about a Greek Orthodox mass I once attended was that there seemed to be no prescribed behavior for the congregation.”

Some stood, some knelt, some sat, some walked; one crawled about the floor like a caterpillar. And the beauty of it was that nobody took the slightest notice of what anyone else was doing. I wish we Anglicans would follow their example. One meets people who are perturbed because someone in the next pew does, or does not, cross himself. They oughtn’t even to have seen, let alone censured.

He finishes with a pointed quote from St. Paul: “Who art thou that judgest Another’s servant?” Note the capital “A.” He means God’s servant.

Read more:

Catholicism: “Here comes everybody,” even the annoying ones

Malcolm seems to dislike formal worship because he thinks it’s too impersonal. Lewis grants the problem that we can run through the forms without actually worshiping. I think of the Masses at which I knock out the Nicene Creed while thinking about something else. But he warns Malcolm that we need the forms. The forms, he says, “canalize the worship or penitence or petition which might without them — such are our minds — spread into wide and shallow puddles.”

Lewis gives three reasons for using a form. First, it holds us to sound doctrine. “Left to oneself, one could easily slide away from ‘the faith once given’ into a phantom called ‘my religion.’” Second, the forms remind him what we ought to ask for, especially when praying for others. “The crisis of the present moment, like the nearest telegraph-post, will always loom largest. Isn’t there a danger that our great, permanent, objective necessities—often more important—may get crowded out?”

Third, they give us what he calls “the ceremonial.” By that he means the attitude that holds together the fact that our relationship with God is one of both the “closest proximity and infinite distance.” He tells Malcolm: “You make things far too snug and confiding.”

Read more:

Pope Francis: How do you pray when someone asks you to pray for him?

At ease in Zion

Lewis ends the letter with an amusing but revealing story. The very Protestant world in which he grew up “did tend to be too cosily at ease in Sion,” he says.

My grandfather, I’m told, used to say that he “looked forward to having some very interesting conversations with St. Paul when he got to heaven.” Two clerical gentlemen talking at ease in a club! It never seemed to cross his mind that an encounter with St. Paul might be rather an overwhelming experience even for an Evangelical clergyman of good family.

Lewis had been formed on good Catholic literature and knew better. He continues: “But when Dante saw the great apostles in heaven they affected him like mountains. … They [the saints] keep on reminding us that we are very small people compared with them. How much smaller before their Master?”

~

For the other articles in the “C.S. Lewis Tells You” series, see: