Bartholomew carries his own skin. Peter Martyr walks about with a knife in his head. Lucy carries a dish that holds her own eyes. The saints, even when shown in glory—in the newness of life that comes in the resurrection—bandy about joyfully with the bumps and bruises (and much worse!) of the life they once lived.

It seems a little macabre, but the very point of it all is to say that death has no role in any of it. Christian life is a comedy—a narrative that ends well.

“Death has been swallowed up in victory,” as St. Paul teaches (1 Cor 15:54), and so the very things that are the mark of the saints’ undoing in this life become in the resurrection the marks of triumph. Skin in hand, Bartholomew and those like him can say with the Apostle “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is you sting?” (1 Cor 15:54-55).

There is, of course, no question of this depiction being taken literally. Neither, though, is it simply an image. What we see projected onto the saints we see first in the account of the Lord’s own entrance into the newness of life. “Put your finger here, and see my hands,” Christ says to Thomas. “Put out your hand, and place it in my side” (Jn 20:25). Jesus rises with the marks of his wounds. He is, as the Book of Revelation shows him, “a lamb standing as though slain” (Rev 5:6).

What should we make of this?

Scripture does not mean to say that Jesus returns to life as did Lazarus (Jn 11:1-44) or the others whom our Lord raised (Lk 7:11-17; 8:52-56; Mt 27:52). They were raised to the same biological life they lived before, a life eventually subject to death.

Not so with Jesus. “Christ being raised from the dead will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him” (Rom 6:9). As the French priest F.X. Durrwell writes, “He did not rise to the life he had before, to this world, to this time.” The marks of his wounds are not the yet-to-be-healed injuries from his suffering and crucifixion. Neither are they the dead scars of a cosmic battle. The marks of his wounds are not defects in his flesh but are, paradoxically, the very form of a body that is fully alive precisely because it is fully configured to love, because it is fully joined to “God [who] is love” (1 Jn 4:8).

It may sound strange, but Durrwell is right when he goes on to say that “The life of glory is a perpetuation of his death.” The life that Jesus leads after the resurrection—the “life of glory”—does not rewind the events of Holy Week but carries them forward beyond the grave. On the cross, Jesus offers himself completely, in loving obedience to the Father who sent him and, despite our rejection, in love for those whom he was sent to gather in. And it is precisely Jesus in this form—Jesus as perfect gift—that rises from the tomb.

Read more:

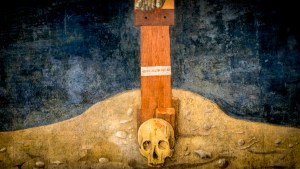

Why is there a skull beneath my crucifix?

Said again, “The life of glory is a perpetuation of his death,” and it is so precisely because Christ’s death is the moment of victory. Resurrection, in us as in Christ, is the carrying forward and making alive of all that divine charity has formed us to be. We rise bearing in some fashion all that we have become by being configured to the love of God. “Put out your hand, and place it in my side” (Jn 20:25) Or for those who have “put on Christ” (Gal 3:27) like Bartholomew and Peter and Lucy: “Touch my skin …”, “Behold my head …”, “See my eyes ….”

Again, though, there is no question of imaging the saints in exactly this way. St. John teaches that “we shall be like [God], for we shall see him as he is.” Even so, “what we shall be has not yet been revealed” (1 Jn 3:4). And more to the point, Paul, speaking of the condition of the body in this life, says plainly that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor 15:50).

What then can we say about Christ’s resurrection and so of our own as well? St. Paul wonders.

Read more:

The Gesù: When art came to the rescue

When writing to the Corinthians, he affirms unmistakably the reality of Jesus’ resurrection. “I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, … that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures” (1 Cor 15:3-4). And again, “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain” (1 Cor 15:14). And yet, when he teaches what that state will be, he entrusts our imagination to the analogy of a seed. “What you sow is not the body which is to be, but a bare seed. … What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable. It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power” (1 Cor 15:37, 42-43).

All is made subject to the One who says “Behold, I make all things new” (Rev 21:5) and who does so not by erasing the past but by taking up and making alive all that divine charity has formed us to be. “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” (1 Cor 15:54-55).

Read more:

Do I believe in the resurrection of the dead?