Ben-Hur (1959) is widely considered the finest biblical epic of Hollywood’s golden age. It won 11 Academy Awards (including Best Picture), and even claimed the final spot on AFI’s 100 greatest movies of all time. It’s also the only biblical epic listed in the Religion category of the Vatican’s “important films.” So naturally, it routinely pops up on lists of films to watch on Easter weekend.

But whether it was all the hype (which, let’s face it, largely hinges on the chariot scene), or the brutal runtime of almost four hours, or the fact that that this “biblical” epic only has periodic touchpoints with the biblical story, I was underwhelmed by Ben-Hur—both as a person of faith and a film buff.

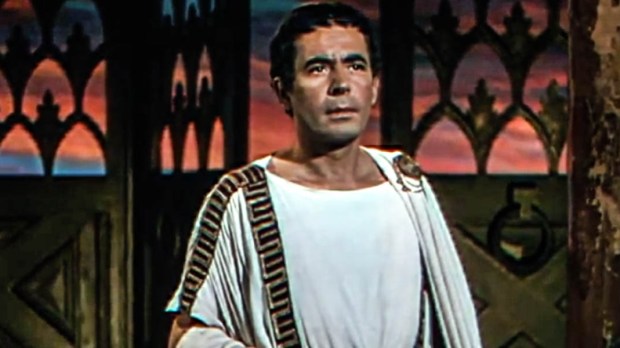

That was not the case with Quo Vadis (1951), a biblical epic that focuses on the early days of Christianity in Rome (and will air in its entirety on TCM at 2:00 a.m. ET on Sunday). Every bit as over-the-top and melodramatic as its successor (it was also shot in Rome, and boasts 30,000 extras), Quo Vadis clocks in at a less mountainous three hours and even edges out Ben-Hur for a better critics score on Rotten Tomatoes.

But I think what really gives Quo Vadis the edge, especially as the better epic for Easter, is its story. Based on a Polish historical novel of the same name by Henryk Sienkiewicz (which was adapted into two silent films in Italy before making its way to Hollywood), Quo Vadis revolves around the fictitious Marcus Vinicius, a noble Roman military commander returning from war. Unlike Judah Ben-Hur, Vinicius quickly becomes entangled in the lives of biblical figures. He first meets with the self-pitying emperor Nero (the “beast” of Revelation), brilliantly played by Peter Ustinov. Soon after, Vinicius falls in love with Lygia, a humble Christian hostage who introduces him to a wandering “philosopher” named Paul. Vinicius is fascinated—but really more entertained—by Lygia’s small and eccentric religious community, whose radical meekness and mercy he can tolerate, but not understand (much less believe in). The Christians meet under the cover of darkness to pray to their “crucified carpenter,” and they’re joined by Peter, a fisherman who knew him intimately.

It’s clear how insignificant Christianity appeared next to the pomp and power of established Roman paganism. It was generally met either with indifference or the suspicion reserved for fringe radicals. They barely make a blip on Nero’s radar. But as the flabby, whiny emperor’s narcissism begins to look more like insanity, he is persuaded to blame his own destructiveness on this little movement. Before long, the Christians are rounded up and brought into the arena to be devoured by droves of hungry lions. Peter, who is leaving Rome, has a vision of the risen Christ (which comes from the apocryphal “Acts of Peter”). “Quo vadis?” Peter asks. “Where are you going?” Christ replies: “If you desert my people, I will go to Rome to be crucified a second time.” The encounter persuades Peter to return to his flock in Rome. What follows are unforgettable scenes of Christian persecution—and Vinicius, who knows heroism when he sees it, is transformed.

This is the first great virtue of Quo Vadis: it’s a vivid reminder of how Christianity started. It did not start as the religion of the social and political establishment; it started as a community of unlikely heroes on the outskirts who lived out a radical love for Christ and each other. It did not hide from the surrounding culture, nor melt into it; it stood boldly within it and proclaimed a greater lord than Nero, even in the face of mockery or suspicion. And what was planted in Rome, the seed that took centuries to blossom, was not an intellectual, moral, or aesthetic program; it was the blood of the martyrs. It’s so easy for us today to lose sight of these roots and identify Christianity with something other than what actually positioned, anchored, and fed it.

The other great virtue of the film is in that great one-liner of Peter’s, which—though the stuff of legend—is a timeless one: “Where are you going?” The question is obviously an important one for Christians, especially as Lent draws to a close. Where do we go from here? What do we do with this momentum of prayer, giving, and sacrifice? How can we embark on a closer walk with God and his people?

But the question is also a pressing one for the broader culture. Fulton Sheen said that it’s the meaninglessness of life that makes it monotonous and wearisome. We become like farmers who plant wheat one week, then dig it up and plant barley the next week, then dig that up and plant watermelon, then dig up that and plant oats. Fall comes, and we have no harvest; the years pass, and we start to go mad. And this is where we are. Obsession for what is immediate—passing experiences, desires, trends, headlines—has come at the cost of what is ultimate and final, sowing boredom and despair all around us.

What will govern and animate our halls and households? What is our end goal after all is said and done? Why are we here? Where are we going?

“Quo vadis?”