Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

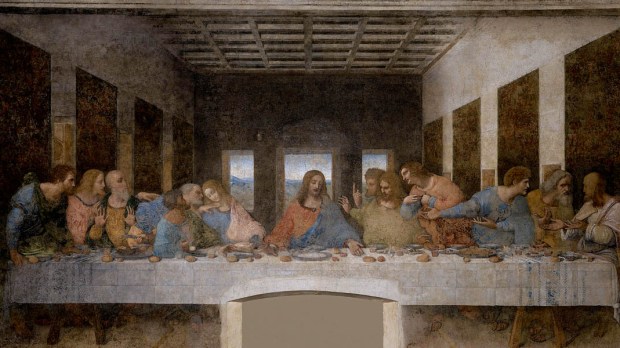

Undoubtedly the most controversial and timeless meal in history is the Last Supper. This significant event is best memorialized by Leonardo da Vinci and his equally contentious painting. Born in 1452, Leonardo da Vinci (literally of Vinci, a region in Florence) had an uninhibited desire for knowledge. A multifaceted genius, his interest in architecture, engineering, sculpting, mathematics, science, anatomy, biology, astronomy, etc., won him the epithet “The Renaissance Man.“

In portraying a narrative chronicled in all four Gospels, Leonardo’s Last Supper brings to life the action of the mind and the soul. It was commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, in 1495 for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The sacramental iconography was meant to create an illusionary extension that transported the dining friars to the “upper room.”

The arena is a rectangular room with coffers on the ceiling and tapestries on the sides. It is flanked by windows at the end of the wall. The balance is set by the gigantic white tablecloth. Christ occupies the center of the composition with two groups of three apostles on each side. The painting reflects the reaction of the apostles to the action of Christ when he revealed, “One of you is going to betray me.”

The response was unsettling and tense. Bartholomew on the extreme left rises on his toes in bewilderment. Simon the Zealot on the extreme right digs into his heels with a “I have no clue” expression to the supposed questions by Matthew and Thaddeus. This contrasting “push and pull”feature creates an sense of energy in-between. Next to Bartholomew, James the Less echoes, “Don’t worry, he doesn’t mean us” while Andrew with his raised hands can be heard saying, “Don’t look at me, I am out of this.”

The next group on Christ’s left is intriguing. James the Greater extends his hands in a “What are you saying, Lord?” gesture, while Thomas, as usual, raises his finger in doubt. Guilt-ridden Philip rises from his seat, taking his turn to say, “Is it me Lord?” The intersection of the raised finger and the extended arms allegorically forms a cross. Thomas’s raised finger also stands as a witness of the Resurrection, of the testimony “My Lord and my God.” Thus the future mingles with the present.

However, the most disputed group is that to Christ’s right. Reminiscent of the Gospel, Peter reclines forward signaling to John to ask Jesus whom he meant. While Peter’s left hand grazes John’s shoulder, his right hand cradles a knife. Of course, “a butter knife,” blurts out one who is unfamiliar with the scriptures. But the knife here foretells Peter’s attempt later that night to slice the ear of Malchus, the high priest’s slave.

Judas, painted on a lower level in shadows, is caught in action by no one but Jesus. Distracted by Peter and John, Judas unconsciously reaches for the same bowl as Jesus. It’s interesting how anxiety overshadowed the wits of the apostles to recognize the traitor. His arm on the table and the purse in his hand presage the betrayal episode. Tipping over the salt cellar on the table, Judas confirms the medieval expression, “betrayal by salt” (i.e., “betraying one’s master”). The contrasting postures of Peter and Judas echo their reaction to their betrayal. While Peter moves towards Jesus, Judas pulls away.

In the midst of this confusion and chaos, Leonardo’s linear perspective draws us to the face of Jesus. Agape, it affirms, Agape! The windowed halo declares his holiness. His serene stance elevates us, creating a sense of the eternal, uniting the earthly and the divine. A second moment is captured here; that of the Institution of the Eucharist. Christ’s hands simultaneously reach out to the bread and wine, symbols of His Body and Blood, a sacrifice that won us salvation. Christ’s posture forms a triangle connoting the Trinity.

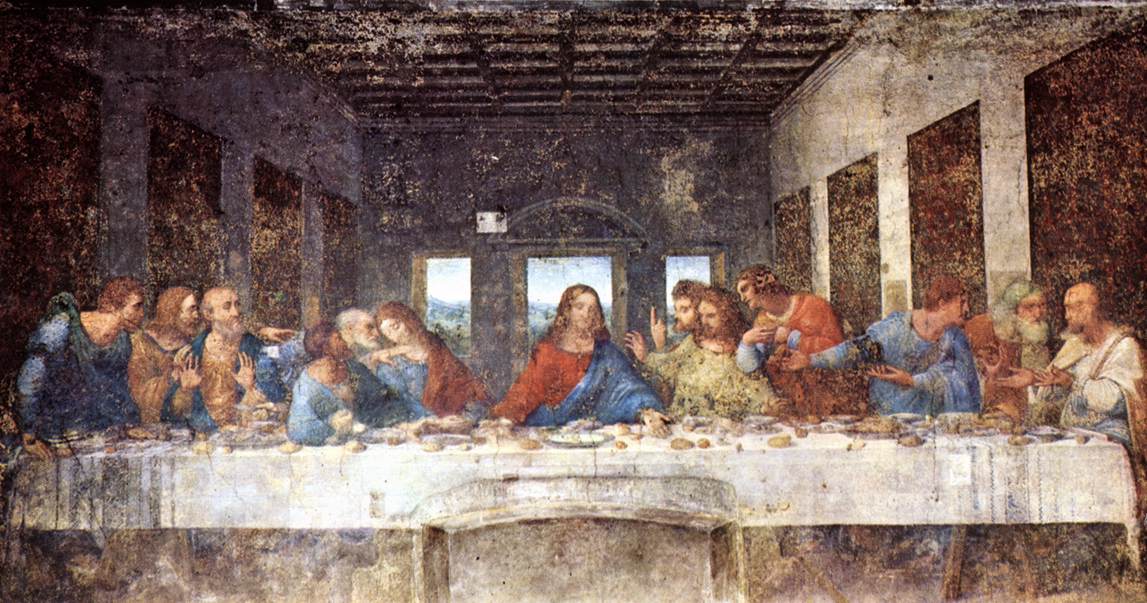

Leonardo uses light and shadow, colors, perception, geometry, anatomy, contrast, depth and unison to create this masterpiece and enhance the narrative. However, he pushed his experiments way too far. Painted on dry plaster with tempera (rather than with the fresco technique that bonds the paint to wet plaster), the painting was soon subject to dampness and disintegration. Yet it reflects the genius of the man.

Mysteries unraveled, secrets told, universally recognized, ceaselessly scrutinized and relentlessly duplicated; the legacy of the Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is timeless. When read through the window of one’s soul, it acts as a catalyst between the natural and the supernatural. It provokes thought, stirs emotion and strengthens faith. It enables us to celebrate the sacrifice and the salvation of He who is eternal!

This article was published in partnership with Indian Catholic Matters.