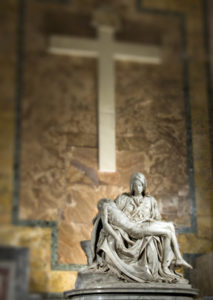

The term Pietà finds its roots in the Italian word for “pity” and the Latin word for “piety.” Heartrending, this composition depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of her son Jesus in her loving arms. With no reference in the scriptures, the Pieta subject developed as a devotional image in 13th-century Germany, where it was regarded as Vesperbild or “the evening picture.” Popularized by the Franciscans, it evoked devotion and faith. This piety was further propagated by colonial influence to the other European nations, including France and Italy.

The most successful and eponymous depiction of the Pieta is undoubtedly that created by Michelangelo. He was only 24 when the French Cardinal Jean de Bilheres commissioned this statue as his funeral monument. Michelangelo at once set to work. He secured a block of Carrara marble, which he later claimed was the most “perfect” block of marble that he had ever used, and began to chisel, carefully transforming the stone into flesh.

So sublime and admirable was its execution that Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of Artists applauds his work with these words: “It is indeed a miracle that a block of stone, formless at the beginning, was brought to such perfection which nature habitually struggles to create in flesh! No other sculptor, not even the most rare artist will all his hard work, can ever reach this level of design and grace.”

The most alluring aspect of the Pieta is the extraordinary affiliation that Michelangelo has constructed between the Virgin Mother and her dead Son. Pyramidal in shape, the body of the beautiful Virgin is enlarged. This was done to carry the physique of a fully grown man, her son, in her lap.

The proportions are not symmetrical and natural. Mary would tower in stature over her Son if she stood up. Michelangelo, in all his creative genius, hides this enlargement with exquisite, lifelike folds of a full-length drapery. The folds set the sculpture into motion and enhance its alternation of light and shadow. The ruffling pleats also highlight Michelangelo’s excellent virtuosity and his skill to shape marble pieces into deeply-cut works of art.

What is unique about this sculpture is the illustration of the Virgin Mary. Nay! She is not described as an aged mother but rather as a young and elegant maiden. Michelangelo received quite a few brick-bats for this imagery. But his depiction was coupled by a virtue. His work never compromised on the theology of the time. As a Third Order Franciscan, Michelangelo believed in the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception and the Virgin’s incorruptible purity. Countering a critique, he is said to have stated: “Do you not know that chaste women stay afresh much more than those who are not chaste? How much more in the case of the Virgin, who had never experienced the least lascivious desire that might change her body?”

Interestingly, Mary does not directly touch the body of her son Jesus. Her right arm gently caresses his flesh through a cloth. This signifies the sacredness of His suffering and the divinity of His form.

Take a look at the rendering of the body of Christ. Heappears not bloodied and bruised but rather peaceful and resigned.

The loss of life is made apparent through the exposed rib cage and the sucked-in abdomen. The expression on His face is gentle, in harmony with his joints, his arms, torso and legs, which are realistically articulated with finely wrought veins and pulses. His exposed thorax reveals His vulnerability and innocence.

After two years the statue was complete and Michelangelo was highly pleased by the outcome of his love and labor. The Pieta stirred his heart, recalling to his mind his very own mother who had passed away when he was only five. Such was his intimacy that he often visited the chapel where it was displayed. On one such visit, he overheard a group of Lombardy tourists praising the statue and acclaiming it to be the work of his contemporary, Gobbo from Milan.

This upset Michelangelo. He found it strange that his work was attributed to someone else. That night he secretly locked himself inside the Church with a little light and chisel\led out his name on the band that ran through Mary’s cloak. However, later he regretted his prompt decision as an indication of his pride and vowed to never again leave his mark on any other work of art.

The world-famous Pieta has not only won substantial adulation but has also sustained dramatic damage. In May 1972, a mentally disturbed geologist, a Hungarian by birth, walked into the chapel and attacked the sculpture with his hammer, shouting, “I am Jesus Christ. I have risen from the dead.” The result of the 15 blows was a disfigured Mary sans her arm and a chunk of her nose. Painstakingly restored, today the statue is housed behind bullet-proof glass and placed at the right of the entrance to St. Peter’s Basilica.

The throbbing soul of the statue is in the relationship that the two figures share. The Virgin is confronted with the reality of the death of her son. Yet the work is not a loud cry of mourning and devastation but rather a serene scene of tranquility and graceful acceptance. As Mary tilts her head forward towards Christ, His head is thrown back in the helplessness of human death. And yet the Virgin recognizes the newness of life.

Look at Mary’s left hand. Exposed, it softly invites us to meditate on the death of her Son. She delicately presents to us the Body of Christ as a path to salvation. What a profound statement of the Renaissance on the essence of the Eucharist, on the essence of Christ whose death was not the end but the beginning of eternal life!

This article was published in partnership with Indian Catholic Matters.