Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

We are in the Dutch provinces of the 1500s. The Dutch Revolt (1568-1648) and the Reformation (1517-1648) brought a strain to the role of the artist. The Protestant insurgency and iconoclasm claimed violence all over the provinces. Churches were sacked, stained glasses crushed and images destroyed. As a result Dutch art witnessed a sharp shift from the sacred to the secular.

Artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Lucas Van Leyden, Jan Sanders van Hemessen and Bruegel, along with a host of other painters and printmakers, started portraying peddlers, peasants, beggars, courting couples, money changers and other local figures in their art works. This gave rise to the “genre” movement that led to the development of Dutch painting in the Golden Age. The humorous portrayal of the “uncivilized man” in art was a call to reflect on human virtues and vices.

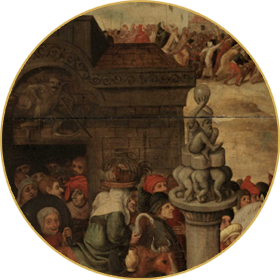

The essence of this genre is experienced through today’s painting under consideration. The subject is that of “Christ Cleansing the Temple.” The theme of the painting itself is revolutionary. Promoted by the Council of Trent, it symbolized the purification of the Catholic Church after the Protestant Reformation. The work is executed by an unknown Netherlandish artist (1563-69, Kadriorg Art Museum, Tallinn) who imitates the nuances set by the famous painters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The painting is bursting with stories, scary characters, mysterious symbols, amusement, proverbs, word plays, moral philosophy and the psychology of 16th-century Antwerp. A huge Temple structure in a mystical style dominates the foreground of the painting. An apocalyptic clock with a hand-shaped dial on the left wall of the Temple strikes 12 and thus announces the arrival of the hour of judgment.

The painting is bursting with stories, scary characters, mysterious symbols, amusement, proverbs, word plays, moral philosophy and the psychology of 16th-century Antwerp. A huge Temple structure in a mystical style dominates the foreground of the painting. An apocalyptic clock with a hand-shaped dial on the left wall of the Temple strikes 12 and thus announces the arrival of the hour of judgment.

Beyond the pillars, in the center of the composition, stands Christ. In utter annoyance, armed with a whip, he drives out the merchants, money lenders and vicious beggars with the words, “Take all this away and stop turning my Father’s house into a marketplace.”

The reaction to this unexpected demeanor is suffused with chaos. The figures cringe, scramble and rush out of the premises in order to escape punishment. They grab hold of their tables and furniture, their animals and goods, pots and baskets, mops and rakes and of course their clanking bags of money. Boisterous clatter fused with bleats, grunts and squeals fills the air. Poised upon a high plinth, Father Abraham and Moses stand witness to this teeming pandemonium. The lamp and the candle burning next to them indicate the sanctity of the Temple; the sanctity which sadly is at stake.

The reaction to this unexpected demeanor is suffused with chaos. The figures cringe, scramble and rush out of the premises in order to escape punishment. They grab hold of their tables and furniture, their animals and goods, pots and baskets, mops and rakes and of course their clanking bags of money. Boisterous clatter fused with bleats, grunts and squeals fills the air. Poised upon a high plinth, Father Abraham and Moses stand witness to this teeming pandemonium. The lamp and the candle burning next to them indicate the sanctity of the Temple; the sanctity which sadly is at stake.

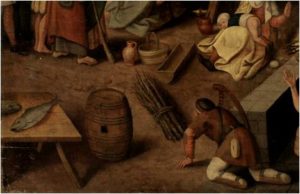

To our left in the foreground lies a table with two herring fishes placed upon it. This depiction recalls the Dutch proverb “There is more in it than an empty herring” or “There is more to this than meets the eye.“ Indeed! For strewn all around the environs of the Temple are satirical scenes advocating Christian morals.

To our left in the foreground lies a table with two herring fishes placed upon it. This depiction recalls the Dutch proverb “There is more in it than an empty herring” or “There is more to this than meets the eye.“ Indeed! For strewn all around the environs of the Temple are satirical scenes advocating Christian morals.

We begin at the foot of the Temple steps. Along with the merchants we notice a variety of beggars and deformed individuals. In the Middle Ages the inclusion of beggars hardly evoked sympathy or compassion. Instead deformity, poverty and disease were seen as a revelation of their damaged spiritual selves. The saying, “An ugly body houses an ugly soul” marked the order of the day.

We begin at the foot of the Temple steps. Along with the merchants we notice a variety of beggars and deformed individuals. In the Middle Ages the inclusion of beggars hardly evoked sympathy or compassion. Instead deformity, poverty and disease were seen as a revelation of their damaged spiritual selves. The saying, “An ugly body houses an ugly soul” marked the order of the day.

The lame with bandaged legs were termed swindlers, for the Dutch proverb that states “lies have short legs.” Notice the lady with a bandaged arm. She begs not in need but rather out of laziness. She uses her child to evoke sympathy, a phenomenon predominant today on our streets. On the other end is a handicapped man with a harp. The harp symbolized polyphonic music, which was considered a sin and a heresy in the Church. As the lame man crawls outwards, he leads us to the next esoteric scene.

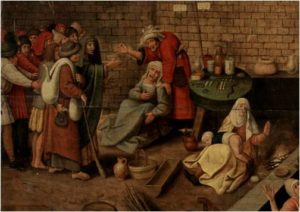

A quack, i.e., a doctor not trained in medicine, is seen performing a dental operation. The art of dentistry was considered a fascinating and inherently humorous task in the medieval age, as long as it was happening to someone else. Without proper tools it was difficult to pull out an individual tooth. If the quack succeeded in doing so, it was a climactic moment of triumph and the tooth would be held up as a spectacle. However this theatrical display was smeared by astute crookedness.

A quack, i.e., a doctor not trained in medicine, is seen performing a dental operation. The art of dentistry was considered a fascinating and inherently humorous task in the medieval age, as long as it was happening to someone else. Without proper tools it was difficult to pull out an individual tooth. If the quack succeeded in doing so, it was a climactic moment of triumph and the tooth would be held up as a spectacle. However this theatrical display was smeared by astute crookedness.

Observe the scene carefully. As the dentist holds up his trophy and as the woman howls in pain, the audience beholds the scene in awe and amazement. This includes the traveler with his walking stick and a goose in his bag. While he looks up in admiration, an accomplice of the quack looks up at his wallet. Thankfully the act does not go unnoticed as the onlookers grab hold of the thief. Could this be a metaphor of the scene within the Temple?

From the foreground we now move to the background of the painting. Towards the left is poised a man exposed in a pillory while another hangs in a basket. The man in the basket is given a knife, an opportunity to cut the rope and free himself. However if he does cut the rope, he would land in the canal and be ridiculed by the bystanders. This scene alludes to the Ecce Homo narrative of the Passion of Christ. The man in the pillory represents Christ who was sentenced to death by the crowds jeering at him, while the figure in the basket is undoubtedly Barabbas, who was chosen to be set free.

From the foreground we now move to the background of the painting. Towards the left is poised a man exposed in a pillory while another hangs in a basket. The man in the basket is given a knife, an opportunity to cut the rope and free himself. However if he does cut the rope, he would land in the canal and be ridiculed by the bystanders. This scene alludes to the Ecce Homo narrative of the Passion of Christ. The man in the pillory represents Christ who was sentenced to death by the crowds jeering at him, while the figure in the basket is undoubtedly Barabbas, who was chosen to be set free.

Condemned to death, Christ is then scourged and made to carry His cross. This scene is depicted in the right background of the painting. Among the throngs of people journeying towards Calvary is Jesus. The religious leaders on horses haughtily charge at Him while soldiers with clubs and spears torment Him.

Interestingly, the painter depicts Christ facing the foreground where a similar scene is taking place. The Temple is being cleansed as the instruments of sacrilege are pushed out. Observe the bas-relief right above the doorway. A limping devil is shown hastily escaping. As Christ steps closer to Calvary, so does the devil step closer to defeat.

Interestingly, the painter depicts Christ facing the foreground where a similar scene is taking place. The Temple is being cleansed as the instruments of sacrilege are pushed out. Observe the bas-relief right above the doorway. A limping devil is shown hastily escaping. As Christ steps closer to Calvary, so does the devil step closer to defeat.

This article was published in partnership with Indian Catholic Matters.