Last December, Vienna’s Natural History Museum found out the hard way that a 29500-years-old figurine –the famous Venus of Willendorf, a Paleolithic age symbol of fertility- was “pornographic.” As Laura Ghianda tried to post a photo of the Venus on Facebook in 2017, she was banned from doing so, as the image allegedly violated the company’s nudity policies.

The museum’s response was quite straightforward. In its own Facebook profile, the museum wrote:

“For 29500 years she has shown herself as a prehistoric fertility symbol without any clothes. Now Facebook has censored it and upset the community (…) an archaeological object, especially such an iconic one, should not be banned from Facebook because of ‘nudity,’ as no artwork should be.”

Although the museum shared this post in January 2018, this only came to be a public matter after several different media outlets specializing in art started to cover the story, The Art Newspaper being the first one of many, with a long article written by Aimee Dawson on February 27.

Facebook ended up apologizing, explaining that although its policies do not even allow any suggested nudity, they “we make an exception for statues, which is why the post should have been approved.”

But that doesn’t seem to be the case with other forms of art: Facebook has also banned German street artists, Courbet (the case went to court), Gerhard Richter, Evelyne Axell, and even Edvard Eriksen’s famous sculpture of The Little Mermaid (to Denmark’s outrage), among others. If specialized media outlets were wondering whether Facebook was “too conservative for contemporary art,” the case of the Venus of Willendorf explains it’s not a matter of contemporary art alone.

Now, nudity is not the only thing Facebook censors. In fact, as Tim Schneider explained in an article published on ArtNet, censorship “is built into Facebook’s DNA.” As the author explains, it’s a problem of both humans and machines:

Both machines and humans are to blame. Much of Facebook’s content review process is carried out by algorithms, as anyone who has followed the ongoing “fake news” junkyard fire knows. Here’s a relevant nudity-based excerpt from The Four, Scott Galloway’s book on the quartet of tech giants now aggressively reshaping our lives: “A digital space needs rules. Facebook already has rules—it famously deleted the iconic image from the Vietnam War of a naked girl running away from her burning village. It also deleted a post by the Norwegian prime minster critical of Facebook’s actions. A human editor would have recognized the image as the iconic war photo. The AI did not.”

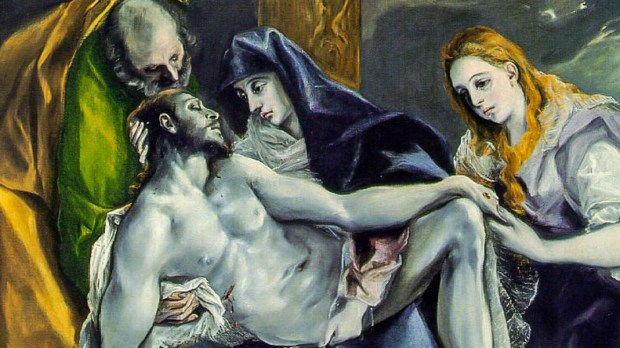

Sure, it’s hard work. But, as Easter approaches, Facebook will have to teach its AI traditional images of Jesus’ Passion might not exactly be considered as containing “shocking or sensational content” depicting “violence or threats of violence.”

Recently, at Aleteia.org, we have found ourselves struggling with Facebooks advertising policy, which has prevented us from promoting some of our own content, because it includes images of the Passion, partial nudity (as depicted in classic works of art), or images of martyrdom in general (again, not snuff-like photographs but just artistic depictions of it). In fact, an image showing the stigmatized hands of Francis Houle was considered by Facebook as containing “shocking or sensational content, including ads that depict violence or threats of violence.”

You can check out some of the non-approved ads we intended to promote (and the explanation we received from Facebook) in the slideshow included in this article. We appealed their decision, and are currently waiting for a reply.