Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

He feels the slightest twinge, the littlest ache, he sees the doctor. An older man I know goes to the doctor all the freaking time. But he’s not a hypochondriac. He hates going to the doctor only slightly less than he hates stepping on Legos. His wife has stage four cancer. Because she’s so sick, he’s got to stay healthy.

So far, the doctor’s always said versions of “You’re getting older.” (She’s polite enough to say “older” and not just “old.”) She’s told him to eat more fiber, take vitamin D, exercise more, get the flu shot, eat fewer hamburgers and fries, and remember that beer has lots of carbs. He leaves her office confident that he can keep taking care of his wife, but also with a list of things to do.

It’s a Lenten life that he leads. In Lent, we get ourselves checked out when we don’t want to. We follow the authority’s orders when we’d rather not. We focus on getting better when we’re happy with ourselves the way we are. And we do it for someone else.

The Lenten life

That’s a lot more important than I realized when I was younger. The Christian disciplines came to me a great gift when I discovered them in my early 20s. My first Christian experiences came among people who thought you just love God and things just happen. Anything else, like all that stuff Catholics did, that was “works righteousness.” Some of them were lovely, Godly people, so apparently sometimes it works like that. It didn’t for me (and it didn’t for many in those circles).

After a few years as an Episcopalian, I started observing Ash Wednesday and Lent, with the thrill of someone who’d discovered the magic diet. The Christianity I’d known emphasized feelings and I didn’t really feel those feelings. But now, with the Lenten disciplines, I could do something. I had the map I needed to get where I wanted to go.

Where I wanted to go was being a better and a holier person. The Lenten disciplines were taught to me as something personal, as a way of working out my own salvation with fear and trembling, as directing my life to Heaven and not to Hell. Maybe I missed something, being young and badly instructed in the Faith, but I’m sure that the dominant teaching I got was individualistic.

You fast to get holier. You give up something for Lent to wean you away from worldly attachments. You read your Bible to know more about God. You pray more to know Him better. All necessary, but also all about me. Me and God, true, but me and God. Lent was about avoiding Hell and getting to Heaven.

Read more:

Why you shouldn’t be aiming for a successful Lent

As I’ve gotten older, I find me less compelling. I hope that has something to do with maturing in the Faith, but it also has something to do with natural adult development. For all sorts of reasons, as you get older, you (most of us) get more comfortable in the world. You get used to yourself, more indulgent of your failings and limitations. You settle for small, incremental improvements.

You lose the burning desire to win, to defeat your enemy. St. Paul tells us to run the race to the end, and in theory, we’d really like to, but that’s really tiring. Many of us stop running and start strolling. At least we’re moving.

Not everyone does this, of course. The saints keep running. But a lot of us do what I’ve described. Decades ago, a friend told me he wanted to be a saint. He meant it. Now he takes comfort in Dante’s vision of Heaven, with the ranks of the redeemed. When he was young, he wanted to be at the front of the line. Now he says he’ll be happy as a clam to stand at the back of the crowd.

Lent for other people

That’s why, for me, it’s helpful to focus on Lent as about other people. I can’t gin up a really strong, driving desire to be better than I am just for myself. But like the older man with his very sick wife, I do feel driven to be a better man for others. God has replaced one motivation with another and a better one.

I want to be a better, holier man for my wife and children, my friends, and others I love, and anyone else I deal with that I should love. My holiness, such as it is, can make them a little holier, bring them a little closer to God. It may just be that I know better what to say to them or that I treat them a little more kindly or that I notice more clearly what they need. But being more Christlike will have some effect — tiny, I admit, but still something.

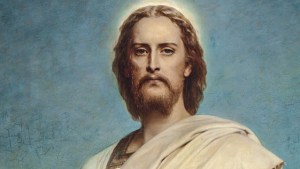

More importantly, I feel more driven to please Jesus. I may be fairly happy with me, but not when I look at Him and imagine what He sees when He looks at me. The Act of Contrition points us to both motivations, but tells us the second’s the key one: “O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee, and I detest all my sins, because I dread the loss of heaven and the pains of hell, but most of all because they offend Thee, my God, who art all good and deserving of all my love.”

Read more:

Pope Francis offers a “worksheet” for Lent: Check it out!