The still silence of the photographic image, for the contemplative eye, is enough to reveal the transcendence of the apparently irrelevant.

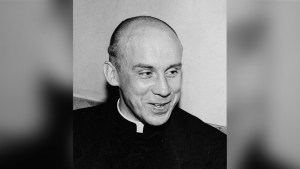

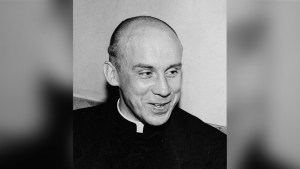

If Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain (his bestselling autobiography, published in 1948, seven years after he arrived at Gethsemane Abbey in Kentucky) made some members of the beatnik generation (back in the 50s and 60s) consider religious life not only as part of the counterculture but also as a genuine existential option, his photography allowed both him and those who would later admire his visual work to think twice about apparently irrelevant things.

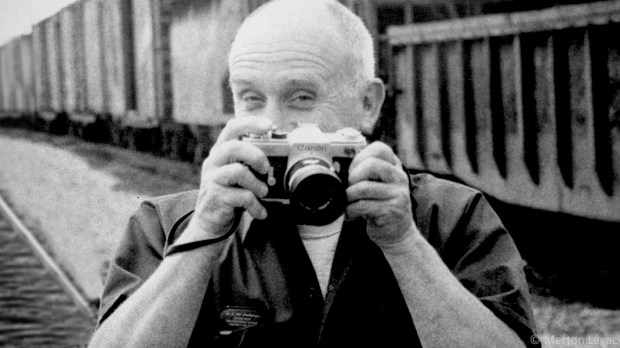

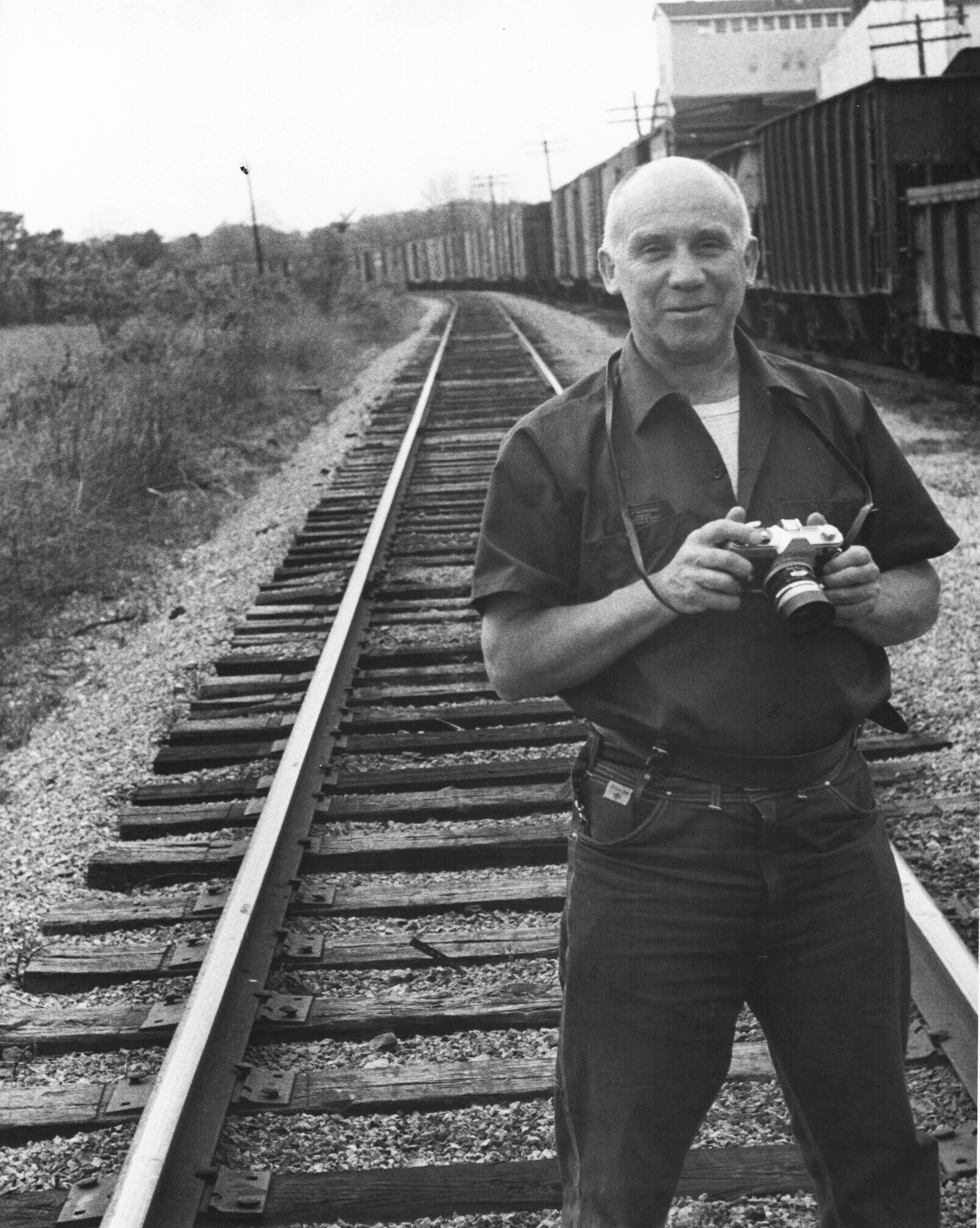

Merton understood his borrowed Canon FX (his friend, the author, photographer and civil rights activist John Howard Griffin, lent Merton his camera) as reminding him “of things overlooked,” helping him cooperate “in the creation of new worlds.”

Read more:

Thomas Merton figured out what we need to “make peace”

Far too many books have been written on the matter, from the famous Esther De Waal’s A Retreat with Thomas Merton: A Seven-Day Spiritual Journey (which matches meditations with some of the monk’s photographs) to Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s Father Louie: Photographs of Thomas Merton (a collection of Merton’s photographs accompanied by excerpts of his correspondence with Meatyard) and Deba Prasad Patnaik’s Geography of holiness (a selection of some of his most contemplative photos, with selected fragments from his own writings).

All these authors share, to a certain extent, the same opinion: Merton’s gaze on objects, through the camera, was always precise, simple, non-intrusive, never contrived. It was a specifically and distinctive monastic – even more, Trappist — approach to photography.

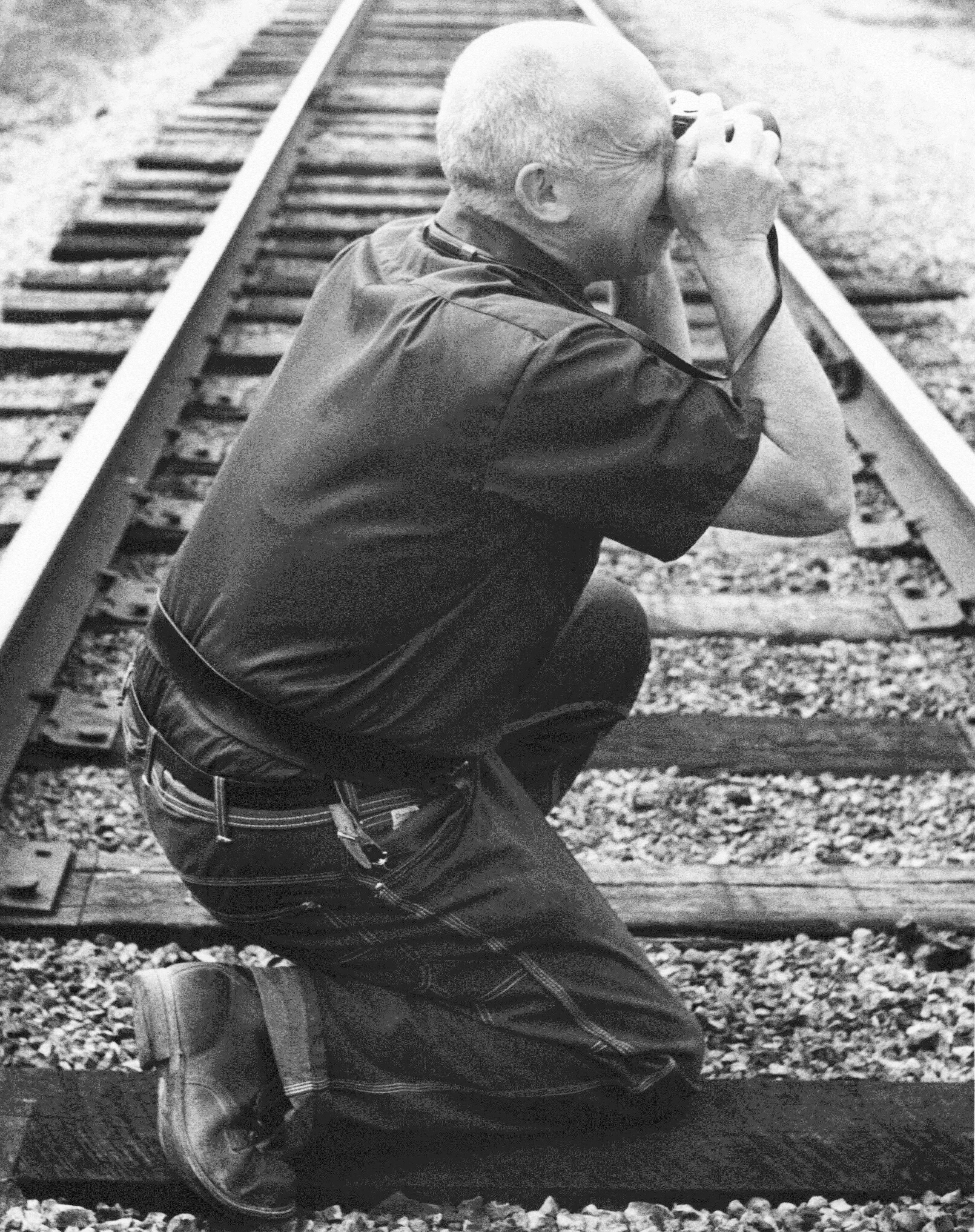

Saying Merton’s photography is monastic is equal to saying his visual work is contemplative, sensu stricto. The tiny lens in the hands of the monk holding a borrowed camera becomes the strict opposite to the magnificent stained glass window of the cathedral. Unlike the latter, able to create a metaphysical environment that allows for an architectural display of a spiritual understanding of light as (not only) a metaphor for God’s presence in the world, the former is just allowing light to go through it, showing the world as it is, in its everyday, physical, common appearance.

Both are mystical approaches to light.

What Merton’s photography might be showing is the abandonment of what seems to be the main aim of photography itself. Rather than pursuing the ownership of a fleeting moment, of an object, or the retaining of both space and time in a two-dimensional surface, contemplative photography – according to Robert Waldron, the author of Thomas Merton, Master of Attention: an exploration of prayer –– seemingly aims to transform the choosing of an angle, an object, a situation, into a matter of abandonment and poverty.

The display of simplicity one finds in Merton’s photography is but an affirmation of things as they are, in their simple, humble, fragile normality. In this kind of opening, in the still, everyday being of things and beings, God reveals Himself.

Merton’s photography can be thought of, in its monastic simplicity, as a 20th-century rendition of the classic memento mori motif. His portraits of ordinary, torn tools – an adobe wall, an old stagecoach wheel, a tall wooden cross in the middle of the field, a lonely chair where no one is sitting, an abandoned hammer, a tin bucket — both transmit a sense of the holiness of created things, and the inevitable passing of time. The very “everydayness” of these objects, when not overlooked, was the key that opened the doors of contemplation.

“It seems to me,” Merton wrote his friend John C.H. Wu, “that mysticism flourishes most purely right in the middle of the ordinary. And such mysticism, in order to flourish, must be quite prompt to renounce all apparent claim to be mystical at all.”

The still silence of the photographic image, for the contemplative eye, is enough to reveal the transcendence of the apparently irrelevant.

A very special thanks to Dr. Paul Pearson of The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University and the Merton Legacy Trust for graciously allowing us to exhibit these photos online.

(Dedicated to my friend, Jeff Bruno.)

~

For those in New York, you can see the exhibit at the Chapel, Union Theological Seminary, 3041 Broadway, New York City, from March 19 to April 13.

Read more:

Thomas Merton figured out what we need to “make peace”