Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

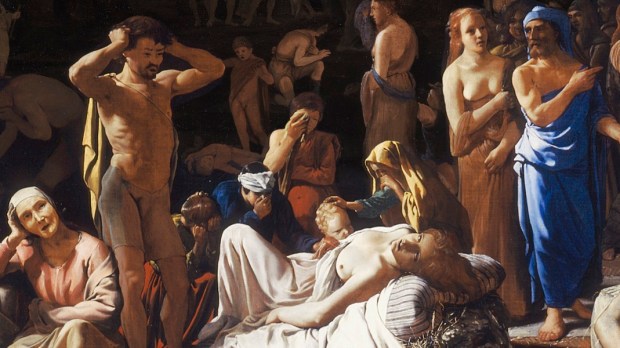

For centuries, history books have taught that rats were the cause of the bubonic plagues of the Middle Ages. Fleas infected in Asia attached themselves to rats who got onto merchant ships sailing to the Mediterranean, the story goes. The end result was the loss of upwards of 60 percent of the population.

But a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests a different disease vector: lice and fleas attached to humans themselves.

The study focuses on the Second Pandemic, a series of plague outbreaks from the 1300s to the early 1800s. These outbreaks include the so-called Black Death, which wiped out a third of Europe’s population in the mid-1300s. The death toll was in the tens of millions.

The study relies on a new mathematical model developed by Katharine Dean, a research fellow at the University of Oslo. As the Washington Post explains, the scientists generated a list of plague characteristics based upon contemporary field observations, experimental data or best estimates:

For instance: The probability that someone could recover from the plague was 40 percent. A louse carrying plague bacteria remained infectious for a period of about three days. A person could carry an average of six fleas.

In addition, plague was thought to spread when fleas abandoned the corpses of rats after becoming infected. But medieval plague records don’t mention rats dying en masse, National Geographic points out.

Some crucial information remains unknown, Dean said. “It’s very hard to grow human fleas in the lab,” she said. The length of an infectious period depends on whether the bacteria simply coat the parasite’s mouth parts or move into its intestines.

Using mortality records from several centuries, researchers could document the rise and fall in plague deaths per week because the disease was so virulent and the signs of infection so obvious, said study co-author Boris Schmid, a computational biologist at the University of Oslo:

Using these parameters, the scientists modeled three scenarios. In one, lice and fleas spread the plague. In another, rodents plus their parasites spread the plague. In a third, coughing humans spread an airborne version of the disease, called pneumonic plague.

The rodent model did not match the historical death rates, says the Post:

The plague must first work its way through the rodent population, at which point the disease bursts into humans. The modeled result was a delayed but very high spike in deaths, which the mortality data does not reflect. The pneumonic plague model also did not fit.

“Human body lice or fleas were the main transmission routes in medieval pandemics,” Schmid said.