言教不如身教。 A teaching with words is inferior to a teaching with one’s own life. – Su Xuelin

My grandmother, born to a large Catholic peasant family in China around 1915, always regretted that she was unable to go to school as her brother did, and she ensured that all her children were well-educated in Singapore, even pawning her jewelry to finance my uncle’s university education.

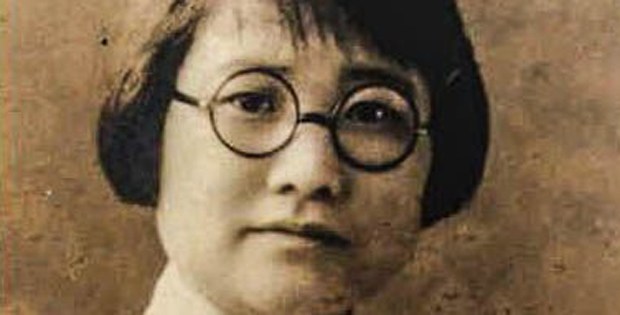

Su Xuelin (苏雪林) was better off in that regard. Born Su Mei in 1897 to a family of officials, descendants of Song Dynasty poet Su Zhe, she was taught basic reading as a child and given the run of her grandfather’s library. After the 1911-1912 revolution, which overthrew the Qing Dynasty and established the Republic of China, girls were finally permitted to enter Chinese schools. Su was one of the first to enjoy this privilege.

She was an outstanding student and traveled to France in 1922 to pursue further studies. Despite death threats from her fiercely anti-religious fellow students in Lyon, Su was baptized into the Catholic Church in 1924, before returning to China. She rose to prominence among the first generation of Chinese female writers and teachers, teaching in the universities of Suzhou and Wuhan – she is seen as the “founding mother” of the modern study of Chinese literature.

Su was recognized as one of the “four guardians” of May Fourth New Literature, the flourishing golden age of modern Chinese literature. The May Fourth Movement was a populist movement sparked by student demonstrations in 1919 against the republican government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, ceding Shandong Province to Japan. This was also known as the New Culture Movement of 1915–1921, where Confucianism was discarded in favor of western principles.

Unfortunately, the May Fourth Movement engendered the Communist Revolution of 1946–1949. Su was staunchly outspoken against the communists, and left for Hong Kong in 1949 to work as an editor and translator for the Catholic Truth Society (CTS). She had been introduced to CTS by Father Frédéric-Vincent Lebbe (Chinese: Lei Mingyuan 雷鳴遠), a Belgian missionary who was tortured to death by the communists in 1940.

Su was also indebted to Chinese Jesuit priest Xu Zongze (徐宗澤), “one of the most prolific Catholic scholars of 20th-century China.” She regarded him as her “second father.” Father Xu was an editor of the Chinese Catholic journal 聖教雑誌 (Revue Catholique) to which Su contributed articles on literature.

Xu was a renowned theologian and polymath who sought ever to meld Catholicism and the ancient ways of his people in a harmonious blend. He said: “To spread the gospel in a country, the first thing necessary is to assimilate it with the people’s thinking and customs; only then can it enter deeply among the people and comprehend their psychology.” Su agreed with this vision, understanding the Catholic faith not as something foreign, but as an encounter with God which is meant for every human being in every nation and culture.

Su’s most famous novel is Thorny Heart (棘心), dedicated to her mother and focusing on the relationship between a traditional Chinese mother and her Western-educated daughter. Like Su, the protagonist Xingqiu studies abroad in France, where she befriends a nun and a consecrated laywoman who spend their lives in service to the poor out of their love for God. She finds this to be in stark contrast to the secularist promise of liberty, which culminated in the violence of the French Revolution. Xingqiu realizes that this is the truly radical revolution which brings true freedom, beyond anything political upheavals can offer: the revolutionary life of self-sacrificial love, the redemptive outpouring of self which is the epitome of human nature in any walk of life.

Su’s vision of Catholicism highlights the value of lowly and humble work traditionally undertaken by women, in a spirit of selflessness and care for the other. She contrasts this with the selfishness of people wantonly following their egoistic desires, ultimately becoming enslaved to them. Su appreciated moderation and the control of one’s emotions, as Confucius did, akin to Aristotle’s and Aquinas’ “Golden Mean.”

Like Edith Stein, Su Xuelin provides deep insights into women’s roles in the Church and society. In modern societies where women are often torn between the humble tasks of home life and the demands of work, and struggle to find their identity in a narcissistic, atomized and sexualized culture, Su, Stein and other women of the Church provide a soothing voice whispering across the generations: one thing is necessary. As Mary quietly assented to God’s will in her life, you can too, wherever you are, and whatever you are doing – it is okay to be obedient, it is okay to sacrifice for those you love, and the choices which modern people deem constricting can actually set you free.

Read more:

The 3 great pillars of Chinese Catholicism

Read more:

The Chinese emperor’s Catholic poetry