Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

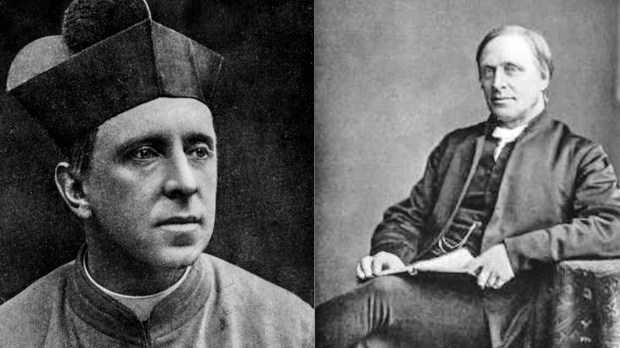

It’s said that Robert Hugh Benson’s conversion to Roman Catholicism was an act of rebellion against his father, Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1883 until his death in 1896. Whether it was or wasn’t, the younger Benson’s spiritual autobiography at least offers grounds for seeing his conversion in that light.

But if so, what difference does it make? God can use inclinations and fears we may prefer not to recognize in ourselves as portals for grace to enter our lives. If latent conflict with a formidable father played a part in this son’s decision to become a Catholic, it doesn’t follow that the conversion was any less sincere.

Robert Hugh Benson (1871-1914) was a prolific author of fiction, apologetics and devotional works, best remembered for the apocalyptic novel Lord of the World, which Pope Francis calls one of his favorite books. His spiritual autobiography, Confessions of a Convert, first published in 1912 and republished by Ave Maria Press, ranks among his best. It’s no exaggeration to call it a minor classic.

Read more:

Why Are 2 Different Popes Telling Us to Read “Lord of the World”?

At its heart stands the imposing figure of Archbishop Benson. The relationship of father and son is summed up in a boyhood incident whose excruciating pain apparently stayed with Benson for the rest of his life.

At Eton the boy was accused of some form of misbehavior, unspecified in the book but evidently serious. Although he was eventually shown to be innocent, his stern father supposed him to be guilty at first. When the elder Benson confronted him, the son was so “paralyzed in mind” that he could offer no defense except “tears and silent despair.” Face-to-face disagreement with the father was simply unthinkable.

Benson doesn’t make the point, but readers will draw their own conclusion: that things weren’t as they should be in this father-son relationship. Of his father Benson writes:

“I do not … think that he made it easy to love God; but he did, undoubtedly, establish in my mind an ineradicable sense of a kind of a Moral Government in my universe, of a tremendous Power behind phenomena, of an austere and orderly dignity with which this Moral Power presented itself.

“He himself was wonderfully tender-hearted and loving, intensely desirous of my good and, if I had but known it, touchingly covetous of my love and confidence. Yet his very anxiety on my behalf to some degree obscured the fire of his love, or, rather, caused it to affect me as heat rather than as light. He dominated me completely by his own forcefulness.”

Benson became an Anglican priest, but he had already begun to suspect that in the quarrel between Anglicanism and Rome, Rome was right. The next several years were spent navigating among High Church groups and their diverse rationales for not converting. In the end—after his father’s death—Benson finally gave up on these doctrinal waverings and acted upon his growing conviction that the true Church had to be one that could rightly be said to “know her own mind” concerning the essentials of salvation. He became a Catholic in 1903 and was ordained the following year. He died in 1914.

Confessions of a Convert concludes with a stretch of lyrical prose recording the author’s ecstatic response to the incarnational Catholicism he encountered in the Holy City. “A sojourn in Rome means an expansion of view that is beyond words,” he writes. Maybe so, but Benson found words that, after all these years, still come close. Readers who cherish the faith he cherished can be glad.