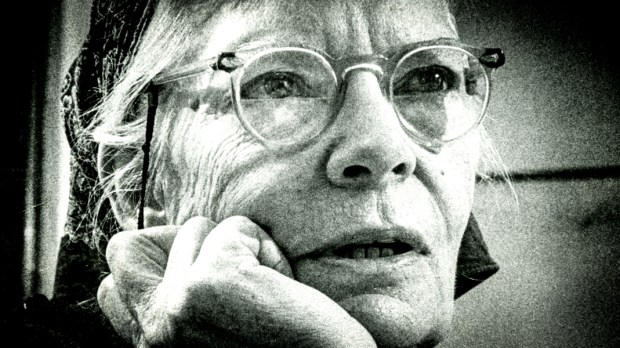

Dorothy Day understood that people need to form a community and seek ties of friendship. With her work and her example, she showed the world that it’s possible to fight for the common good, for justice, and for others within an individualistic society. She fought against the feeling of loneliness and that’s why she titled her autobiography The Long Loneliness. In it, she explains:

“I was alone, mortally alone. And I would soon see, again and again, as I already had on other occasions, that women especially are social beings who are not content just with having a husband and a family; they also have to have a community, a group, an exchange with others. A son or a daughter is not enough. A husband and some children, no matter how busy they keep you, are not enough either. We women, both young and old, are especially victims of the long loneliness, even in the most active years of our lives.”

Journalist and social activist

Dorothy Day was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 8, 1897. She grew up in a modest home. Her parents were Protestants and married in the Episcopalian church. She was not baptized, nor did she have any devotions or piety.

But an event marked her at age 8 — the San Francisco earthquake: “My clearest memory of the earthquake is the widespread human warmth and goodness that followed it. […] After the earthquake, Christian charity filled people’s hearts” (Dorothy Day, My Conversion). This event, which she lived through, became the seed of the great Catholic Workers Movement, where she would welcome the outcasts of the earth.

She began her university studies at the University of Illinois and got to know the ideals of the proletariat. She fell in love with the power of the masses thanks to Marxist ideas: “It was the poor and the oppressed who would carry her away: they were collectively the new Messiah that would redeem the persecuted, scourged, imprisoned, and crucified.”

At age 18, she left the university and began to write and engage in activism in New York. She worked at a newspaper and lived in a small room where she only went to sleep after long days of work. At that time, she was very belligerent. She celebrated the Russian Revolution, was imprisoned for demanding women’s right to vote, and started a hunger strike in jail that left her isolated and deprived of company.

During those days, she asked a guard for a Bible (it was the only book they were allowed to have) and began to feel tormented by the idea of God. She tried to hide it, but little by little it was taking her over. She once wrote that even after spending the night in a pub, she crept into a church and knelt down in the back pew.

Her romantic life was not simple either. She met a Jewish boy, Lionel Moise, and fell in love with him. She was pregnant and felt forced to abort. Shortly after, she married Barkeley Tobey, but their marriage didn’t last more than a year. She fell in love again, this time with Foster Batterham, and got civilly married. As she put it, he was “an anarchist, an Englishman by descent, and a biologist.”

Conversion and the world of workers

She became pregnant again and lived with great happiness. “I’m surprised that I started to pray every day,” she explained in her autobiography. She named her daughter Tamar and, after much reflection, knowing that her husband would leave them, she also decided to get baptized. She confessed and received communion for the first time.

From that moment on, her religious life would deepen, and she would meet Peter Maurin. With him, she raised up a major work to help the lower social classes: The Catholic Worker. Peter Maurin had the Catholic intellectual weight and she brought her boundless strength and love for the poorest, inspired by the Gospel. Both made history.

The Catholic Worker came to be a newspaper with a circulation of more than 150,000 copies, and thanks to Dorothy’s efforts, they created a network of hostels that became a social and charitable reference point in the United States. It currently has 227 communities.

She never stopped fighting for workers. She met and visited Mother Teresa in Calcutta and on her 80th birthday, she received warm congratulations from Pope Paul VI. Pope Francis held her up as an example in his first speech in the United States, and now, as a Servant of God, she is expected to become canonized at some point in the future.

She always wanted to be remembered with these words: “As a humble believer who did what she could to live in accordance with biblical teachings, who continued studying, for example, the sermon on the mount.”

Read more:

Dorothy Day: In Her Own Words

Read more:

Homosexuality and Catholic evangelization: “The Dorothy Day Way”

Read more:

Dorothy Day, Mother Teresa, and the 5-Finger Gospel

This article was originally published in the Spanish edition of Aleteia and has been translated and/or adapted here for English speaking readers.