Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

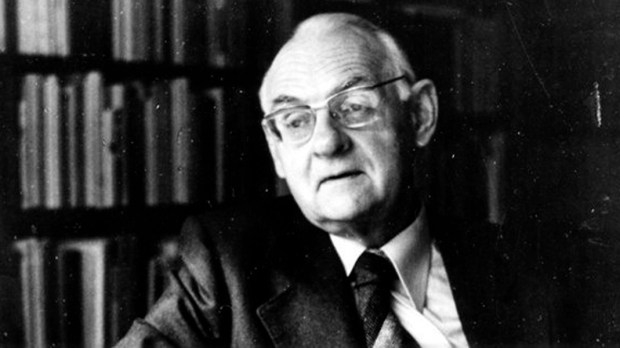

Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988) ranks among the two or three most important Catholic theologians of the 20th century.His life is a fascinating one of controversial friendships, difficult choices, extensive dialogue and prodigally fruitful Christian mission. Balthasar started a publishing house (Johannes Verlag) and a community for Christian formation, the Community of Saint John (Johannesgemeinschaft), both of which remain active today. His greatest theological work is the 15-volume (English version) trilogy of Theological Aesthetics (Beauty), Theological Dramatics (Goodness) and Theological Logic (Truth). Each set of volumes explores the relation of Divine Glory as revealed in scripture and tradition to the beauty, goodness and truth of the world as reflected through great thinkers, writers and artists and also as known in light of revelation and grace. It is this light, reflected most brilliantly through the life, teaching and mission of Jesus Christ, that presents the measure for all inner-worldly beauty, truth and goodness.

Balthasar’s mind is best characterized as synthetic and contemplative: one sees the whole first and parts in light of the whole. We might think of this as the anti-Humpty Dumpty theology. Whereas modern Christians often take their roles as king’s men scouring shards of God’s Word to cobble something together, Balthasar suggests first receiving God’s Word as one would a beautiful work of art or musical score, allowing the work to present its basic contours, connections and significance through a “beholding” or “contemplation” of its form. It is only the overriding form or pattern of God’s revelation that will allow the pieces to fall nicely together and come into focus. Indeed, “form” is one of Balthasar’s most important ideas.

The Greeks, Balthasar judges, were right to see the world as lit up, radiant or epiphanic. Rarely contemplated, perhaps because always already occurring, is that this light shines from form, from shapes and patterns that permit minds like ours access to meaning, to light. Form is the exterior shape of a depth or interiority that shines through it. Form differentiates rock from plant, plant from animal, animal from human being, one musical score or poem from another, poetry from philosophy, etc. Apart from form, the human desire or eros towards knowledge would be futile.

The human creature lives ec-statically, meaning always beyond itself, in a world that gives itself in infinite shapes, colors and sounds. In other words, the eros or desire of our minds to go outwards encounters a world always already giving itself, expressing itself in form intelligible to our minds. This proportion of mind to world is a remarkable gift; it is also a gift, on Balthasar’s account, that the world is always more—more rich, more dense, more varied—than our minds can grasp at any one time. This too is a gift that calls us towards others in dialogue.

To express the meaning of all of this—its beauty, truth, goodness, but also its sorrows and terrors—has been the mission of poets, philosophers, artists, prophets, religions across cultures and times.Such thinkers and the cultural forms they produce express what they conceive to be truly worthy of praise.

God too, analogously speaking, is an artist, a poet, a philosopher who enters into the very place we can naturally encounter him: in the being of the world, in a particular form that is his work of art.God reveals himself—and thus Truth, Goodness and Beauty—through the dramatic story of Israel’s faith and, ultimately, in the pattern of Jesus’s life: his prayer, obedience to the Father, humility, love for neighbor and enemy, truthfulness, forgiveness, passionate care for the least and most despised in society, and total self-giving exorbitant love.Under this measure and inspiration, knowledge is not for power but service, goodness not for heroism but without the left hand knowing what the right hand is doing, and beauty not the superficial image, but the compelling form of a life given for others. The movement here, for Balthasar, offers a participation in Christ’s divine mission not through an elite mystical ascent, but rather through a descent to those most in need where, paradoxically, Christians find the face of God and the joy of his image.