Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Christmas is the incarnation of God, which is, of course a reminder that ours is an incarnational faith. As Mike and Grace Aquilina put it in their new book A History of the Church in 100 Objects, “The Incarnation is the heart of the Christian creed and the point of every Mass. It is the definitive revelation of God. When the Son took flesh by the power of the Holy Spirit, he revealed God’s eternal fatherhood. This is how the world came to know God as a Trinity of divine persons and share the inner life of the Trinity through the sacraments.”

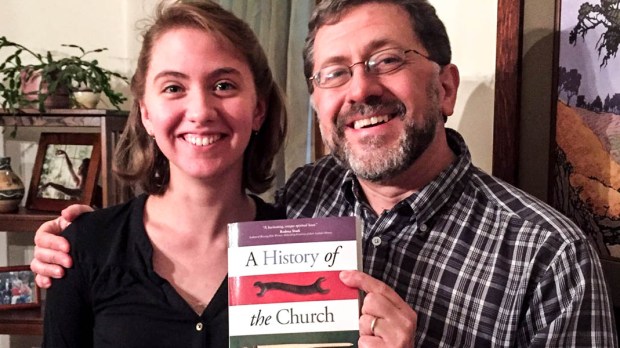

Mike Aquilina, a writer of many books on Christian history, talks about this collaborative collection he’s done with his daughter and what it can mean for the practice of faith in the world.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: Why 100 objects?

Aquilina: Well, we didn’t invent the genre. Neil MacGregor did it first for the BBC, in his series “A History of the World in 100 Objects,” which later became a bestselling book. It was such a neat idea, and there were immediate imitators: A History of Baseball in 100 Objects, and Football, and Cycling, and Birdwatching, and World War I, and Ireland, and Australia, and even the town of Cheltenham. But none of those subjects have as much cool stuff as Catholicism. At least that’s what we thought, and our publisher Tom Grady agreed.

Lopez: What’s a Certificate of Sacrifice and why is it relevant to the modern day?

Aquilina: In the middle of the 3rd century, the Roman Empire was facing many crises, not the least of them political disunity. The Emperor Decius decided that the way to overcome these problems was to get every single person in the empire to offer sacrifice to the gods who protected the emperor. As soon as you sacrificed, you got a libellus, a piece of paper certifying that you’d done your duty of civic religion. Hundreds of these have survived in the sands of Egypt. But Christians could not, in good conscience, do what the emperor was demanding, so they traveled with no libellus, and for this they could be executed. Many of them were. Why is this relevant? Think about our professions today — medicine, law, government. So many people are asked to sacrifice their principles for the sake of certification, advancement, or election. So many people do exactly what Caesar requires. That’s the greatest tragedy.

Lopez: Do St. Peter’s chains offer a message for us today?

Aquilina: “A disciple is not above his teacher, nor a servant above his master; it is enough for the disciple to be like his teacher, and the servant like his master” (Matthew 10:24-25).

Lopez: Why delve into “the Church and the Empire” when we ought not be of this world?

Aquilina: We’re not of it, but we’re sure in it, up to our eyeballs and then some, and we’re called to sanctify it. Otherwise we would have no reason to write history.

Lopez: Why on earth would you include “A Sign of the Inquisition” in your book?

Aquilina: We didn’t shy away from the stories that are hard to tell. This isn’t a work of propaganda, though I hope it’s an effective work of apologetics. Catholicism gives us a profound way of understanding the sins of our own history. In no way do these conflict with the story we tell about sin, righteousness, and judgment. All the saved are sinners.

Lopez: Ditto “An Antipope’s Seal”?

Aquilina: Ditto. Antipopes in particular often provide comic relief to a historical narrative. There are quite a few of them active today, and you can catch them on YouTube. True popes wear outlandish headgear with dignity, but the crown always seems to sit comically on the head of an antipope.

Lopez: Why Cardinal Newman’s desk? What was the most important thing written there?

Aquilina: Letters! What was most impressive to us was the number of people who converted to Catholicism through the personal apostolate of Cardinal Newman. He didn’t just evangelize through his extraordinary writing. His primary witness was friendship.

Lopez: How are you as prolific as you are? I have a few new ones from you on my desk, and they always seem to coming in.

Aquilina: I’m highly motivated, since I have children to feed — and since I think the work I’m doing is urgently needed. I’m certain that others could do it better, and I’m sorry that those people don’t have time. But there are so many people misinformed right now about things I hold dear: the Christian faith and its beautiful, comic, tragic history. So I keep writing, hoping that someone else will eventually show up and take over. Maybe someone like my daughter Grace.

Lopez: Do you have time to read? If so, what are you reading right now?

Aquilina: Most of my reading is ad hoc. It’s research for the book I’m writing next. I’m not complaining. As I said, I write about what I love. My pleasure is poetry. Lately I’ve been reading the poets Samuel Hazo, James Matthew Wilson, Ryan Wilson, and Edward A. Dougherty.

Lopez: What was the experience of father and daughter writing together?

Aquilina: I loved every minute of it. Gracie and I love to talk, and these objects were the stuff of many wonderful conversations.

Lopez: Is there a most obscure object that you’d like to rise to the surface and become more of a household name?

Aquilina: Grace and I delighted in the obscure objects. We were gleeful when we found a parking pass for bishops attending the Second Vatican Council. That ordinary object really tells the story of Vatican II. It was the first Council to be summoned in the age of easy global travel, so many, many bishops could attend. That created a parking crisis in the city of Rome.

We do hope that “unguentarium” will become a household word, once people read our chapter on that particular — and very important — 4th-century object.

Lopez: Do you have a favorite object, one with significant resonance to your life or the state of the world today? That has helped you with your own faith?

Aquilina: My favorite was the bookshelves of St. Ignatius of Loyola. He was an adventurer, a womanizer, a prideful man. And then he got horrifically injured by a cannonball — and further injured by medical care. The man of action found himself confined to bed, incapable of any action whatsoever. All he could do was read, and all that his sister had to read was popular Catholic books. They weren’t heady, literary or theological masterpieces, just the stuff of popular devotion. Well, those books proved to be the occasion of his conversion. Those bookshelves give me hope that my books might do some good.